chapter 1

The Path of Sound

The substantive material of this introductory chapter should appear familiar to the reader of this monograph. It is included as a point of departure for the rest of the text in an effort to prepare the reader for what it contains and how it is organized. Nevertheless, certain statements may contain new information for any particular reader, depending on his or her background.

My research on sound transmission in the ear began with the inner ear, then moved to the middle ear, finally, to the outer ear for a short period of time. This order is contrary to the direction of sound propagation. But, as every electrical engineer who deals with networks and transmission lines knows, this is the correct order because the performance of every preceding stage depends on the input properties of the following one.

To be accurate, I should mention that my early research on the cochlea concerned only mathematical theory of postmortem preparations. No necessary empirical information was available for the live cochlea. My experimental and theoretical work on the latter did not begin until the 1970s, after my research on the middle and outer parts of the ear had been completed. This work was made necessary by new evidence indicating that not all the conclusions based on postmortem cochlear preparations were valid for the mechanics of the live organ.

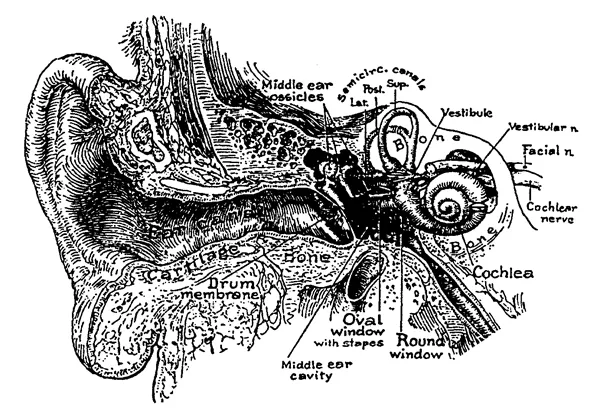

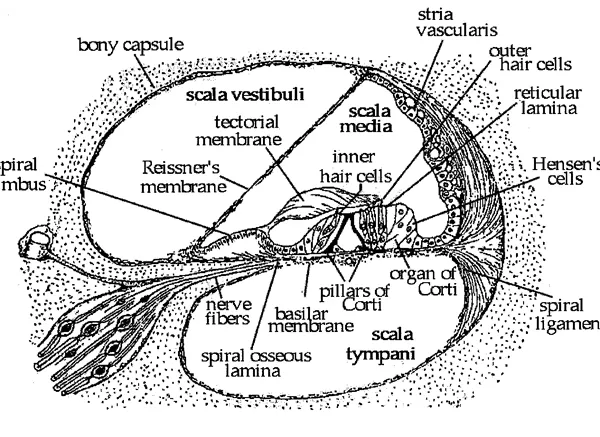

Since the input properties of the sound transmitting parts of the ear have become known by now, it is possible to follow in this book the direction of sound propagation. This is done beginning with the outer ear all the way to the hair cells in the cochlea of the inner ear which, acting as microscopic microphones, transduce the mechanical vibration associated with sound into electrochemical processes culminating in nerve action potentials. The path does not stop at a dead end, however, because part of the generated electrochemical energy, enhanced by metabolic energy, is returned to the mechanical vibration through a positive electromechanical feedback. The first part of the path can be visualized best by looking at a longitudinal section of the outer and middle ear, as sketched in Fig. 1.1. The sketch also includes the fluid filled canals of the inner ear with a clearly visible spiral of the cochlea, its auditory part. Because in reality the human inner ear canals are embedded in hard bone, the artist had to mentally chip it away to show their course. The cochlear canal has been opened partially to show that it is divided longitudinally by a partition. The partition determines the mode of sound propagation in the cochlea. As shown in Fig. 1.2, it is not a simple structure but consists of a multilayered plate, called the basilar membrane, which supports a complex cell mass containing the sensory hair cells stimulated by its vibration. The partition with the hair cells is essential for hearing, and the analysis of its structure and function occupies a substantial part of this monograph.

FIG. 1.1. Sketch of the longitudinal section of the outer and middle ear with visualized cochlea, which is opened at one location to indicate the inner partitions—the basilar and Reissner’s membranes. (Modified from Brödel, 1946; cit. Zwislocki, 1984). Wever, E. G., & Lawrence, M: Physiological Acoustics. Copyright © 1954 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

FIG. 1.2. Sketch of the cross section of the cochlear bony canal. (Modified from Rasmussen, 1943; cit. Zwislocki, 1984).

When sound strikes the human head, most of its energy is reflected but some of it enters the auricle and the ear canal and is led to the tympanic membrane where, in the speech frequency range, about half of the incident energy is transformed into the vibration of the membrane and half is reflected again. From the point of view of auditory sensitivity, the two reflections and an added one in the concha of the auricle may appear as a waste of sound energy, but the reflections are used well by the nature. They serve to enhance the auditory sensitivity in certain frequency regions important in auditory communication. In addition, the reflections at the head and the auricle depend on the direction of incident sound and produce intensity and time differences between the two ears, enabling us to localize the source of sound.

The vibration of the tympanic membrane is transmitted to the three ossi-cles of the middle ear—the malleus, incus, and stapes, which connect the tympanic membrane to the oval window of the inner ear. The long process of the malleus, the manubrium, is embedded in the tissue of the tympanic membrane and increases its stiffness, improving in this way sound transmission to the ossicles. The malleus is connected to the incus through a massive joint that can be considered as practically rigid from the point of view of sound transmission, except at very high sound frequencies. When the manubrium is entrained by the vibration of the tympanic membrane, the first two ossicles rock around an axis determined in part by the ligaments that hold them in place and in part by their center of gravity, the latter becoming particularly important at high sound frequencies.

The long process of the incus is attached by a small cartilaginous joint to the stapes, which is the smallest bone in the human body. The rigidity of the incudo-stapedial joint appears to vary among mammalian species. According to indirect measurements, it seems to be practically rigid in guinea pigs, quite flexible in Mongolian gerbils and semirigid in humans. When the incus rocks, its long process pushes the stapedial footplate in and out of the oval window, where it is held by the annular ligament. In this way, sound is transmitted to the inner ear.

The advantage of the elaborate system of the ossicles and their rocking motion, as compared to a simple rod-like columella encountered in birds and amphibians, did not become clear until Békésy (1949) demonstrated that it is more stable in sound transmission and prevents certain distortions. It also acts as part of a mechano-acoustic transformer enhancing the sound pressure at the entrance of the inner ear relative to the sound pressure at the tympanic membrane, as was already pointed out by Helmholtz (1877) in mid-19th century.

It is not always clear that the air-filled cavities of the middle ear, which are in communication with the large volume of air in the pneumatic cells of the mastoid bone, play an important role in auditory sound transmission. In fact, they do not only provide a cushion of air necessary for an unimpeded vibration of the tympanic membrane but, as a result of their complicated geometry, also affect the dependence of auditory sensitivity on sound frequency. As I was able to demonstrate (Zwislocki, 1975), they combine their effects with those of wave reflections in the outer ear and those of ossicular mechanics to provide a surprisingly uniformsound transmission in the range of speech frequencies.

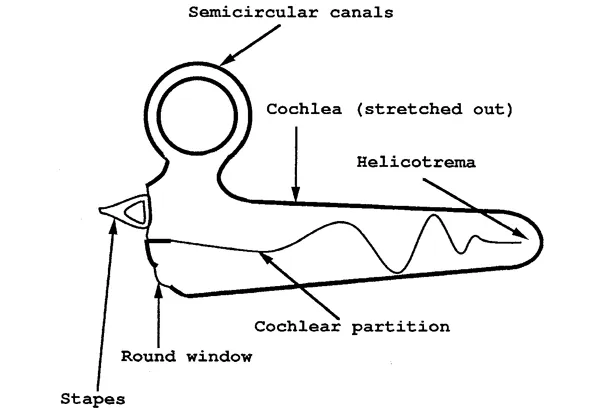

Sound is propagated in the outer ear in the form of compressional waves and, in the middle ear, through ossicular vibration. In the inner ear, the mode of sound propagation changes again and takes the form of transversal waves that run along the cochlear partition, somewhat like waves on the surface of water, as illustrated schematically in Fig. 1.3. It should be pointed out that the transversal waves are made possible by the round window of the inner ear, which is situated on the opposite side of the cochlear partition from the oval window. In the absence of the round win-dow, vibration of the stapes would simply compress and decompress the inner ear fluid, producing little motion because of small compressibility of the fluid. The flexible membrane of the round window provides an easy release for the alternating pressure by allowing the cochlear fluid to oscillate between it and the oval window. Because the two windows are on its opposite sides, the cochlear partition is forced to participate in this oscillation. It is true that the helicotrema opening at the apical end of the cochlear canal provides a fluid passage between the two sides of the partition, but the cochlear waves do not reach it, except at very low sound frequencies, as illustrated. The wave pattern shown in the figure is consistent with a large number of measurements. It shows that the wave amplitude increases up to a maximum as the wave progresses toward the apex, then decays rapidly, whereas the wave length decreases continuously.

It has been established experimentally that the location of the maximum depends on sound frequency. For high frequencies it is near the oval window and moves away from it, toward the end of the cochlear canal, as sound frequency is decreased. Following a suggestion of Helmholtz’s (1877, 1954), who predicted the existence of the maximum, its location has been believed to be the physiological code for the subjective pitch of sounds. Indeed, some measurements appeared to show a similarity between the ways the location and the pitch depend on sound frequency.

FIG. 1.3. Sketch of transversal waves on the cochlear partition, whose amplitudes are magnified.

The cochlear waves were first observed by Békésy in 1928 on postmortem preparations of human temporal bones and were investigated by him in greater detail in 1947. I explained their nature mathematically in terms of established physical laws, the first publication appearing in 1946, a more extensive one in 1948. These early discoveries are still valid in principle, but subsequent experiments on live animal preparations and associated theory have introduced important modifications. They revealed that the vibration maximum in a live cochlea is much sharper than after death, and that its location depends on sound intensity, so that it cannot be a direct code for pitch that remains practically invariant. They also revealed that the relationship between the vibration of the cochlear partition and the stimulation of the sensory cells is much more complex than originally assumed.

As the waves are propagated along the cochlea, the cochlear partition is deflected transversally back and forth at each location. The pattern of this deflection in the width direction approximates a rocking motion of the basilar membrane around an axis situated near the inner pillars of Corti. According to the classical theory, this motion produces a shear motion between the top of the organ of Corti, the reticular lamina that holds the hair cells, and the tectorial membrane that rotates around a different axis, the ridge of the spiral limbus. The shear motion, in turn, produces deflection of the hairs, or stereocilia, of the hair cells, leading to a depolariZation of the hair cells and excitation of the nerve fibers that end on them.

In the following chapters, I analyze separately sound processing in each of the main parts of the sound-transmitting system of the ear. The analysis is based on my past work and, in part, constitutes its review and synthesis. However, much unpublished material is added, and the analysis is updated to coincide with the cutting edge of current research. This is particularly true for the cochlea whose function is so complicated that it defies comprehensive description in a journal article. Accordingly, I gave up on publishing exhaustively the results of my current research on the mechanics and electromechanics of the cochlea in journal articles and have reserved it for this book.

The outer and middle ear each occupy one chapter, but the cochlea occupies three, not only because of the volume of research it has commanded but also because it appeared to me that its complex function can best be explained in steps. Therefore, the first chapter in the sequence concerns the postmortem cochlea that is greatly simplified by comparison to the live cochlea. Once the principles of the simplified function are understood, it is easier to comprehend those of the more complex one.

The analysis of each part of the ear includes the following five aspects not necessarily in the order listed here: description of its structure, measure-ment of its dynamic characteristics, independent determination of its physical constants, construction of a mathematical, network—or even physical model and, finally, comparison of the model’s characteristics with those measured on the natural system. The comparison has a double purpose— validation of the model, which is always a simplified cartoon of the real system, and determination of the effects of individual elements of the system. The extent to which the model characteristics agree with the natural ones may be regarded as a measure of our understanding of the system. Knowledge of the effects of the system’s elements is not of purely academic value but can have applications to medical diagnostics, as became clear to me in particular on the occasion of my analysis of the middle ear function.

REFERENCES

Békésy, G. v. (1928). Zur theorie des hörens: Die Schwingungsform der Basilar membrane [On the theory of hearing: The form of vibration of the basilar membrane]. Physikalische. Zeitschrift. 29, 793–810.

Békésy, G. v. (1947). The variation of phase along the basilar membrane with sinusoidal vibrations. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 19, 452–460.

Békésy, G. v. (1949). The structure of the middle ear and the hearing of one’s own voice by bone conduction. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 21, 217–232.

Brödel, M. (1946). Three unpublished drawings of the anatomy of the human ear. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Helmholtz, H. L. F. (1877). On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music (reprinted second English edition by Henry Margenau (1954), Dover Publications Inc., New York).

Rasmussen, H. T. (1943). Outlines of Macro-anatomy. Dubuque, IA: Brown.

Zwislocki, J. J. (1946). Über die mechanische klanganalyse des Ohrs [On the mechanical transient analysis by the ear]. Experientia, 2, 10–18.

Zwislocki, J. J. (1948). Theorie der Schneckenmechanik: qualitative und quantitative Analyse [Theory of the mechanics of the cochlea: Qualitative and quantitative analysis]. Acta Oto-Laryngologica Supplement, 72, 1–76.

Zwislocki, J. J. (1975). The role of the external and middle ear in sound transmission. In E. L. Eagles (Ed.), The Nervous System, Vol. 3. New York: Raven.

Zwislocki J. J. (1984). Biophysics of the mammalian ear. In W. W. Dawson & J. M. Enoch (Eds.), Foundation of Sensory Science. Berlin, Germany: SPRinger.