eBook - ePub

Geography in the Twentieth Century

A Study of Growth, Fields, Techniques, Aims and Trends

- 630 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geography in the Twentieth Century

A Study of Growth, Fields, Techniques, Aims and Trends

About this book

This title, first published in 1951, examines the growth, fields, techniques, aims and trends of geography at the time. The book is divided into three parts, of which the first deals with the evolution of geography and its philosophical basis. The second is concerned with studies of special environments and with advances in geomorphology, meteorology, climate, soils and regionalism. The last part describes field work, sociological and urban aspects, the function of the Geographical Society and geo-pacifics. Geography in the Twentieth Century will be of interest to students of both physical and human geography.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geography in the Twentieth Century by Griffith Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

EVOLUTION OF GEOGRAPHY AND ITS PHILOSOPHICAL BASIS

The frontier where science and philosophy meet, and where the conclusions of one are handed across to be the premises of the other, should be taken as the vital centre in the wide realm of thought.

LORD SAMUEL

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: THE SCOPE OF THE VOLUME

Griffith Taylor, born at Walthamstow, London, England, was educated at the Universities of Sydney and Cambridge. He was Senior Geologist in the British Antarctic Expedition of 1910–13; Head of the Department of Geography at Sydney 1920–8; Professor of Geography at the University of Chicago 1928–35; Head of the Department of Geography at Toronto University since 1935. He has written a score of books on geography, geology, meteorology, and anthropology.

PART I. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE ENVIRONMENT

THIS volume by twenty American, British, and European geographers is an attempt to answer questions which are engaging the attention of all geographers. What are the salient features of our modern geography? What are we trying to accomplish? How have our ideas as to what are the important fields of our discipline changed during the last fifty years? How do our studies touch the fields of allied disciplines? Have America, Britain, France, Germany, and the Slav nations and even Canada produced special contributions, determined in part by the somewhat different problems which engage the attention of workers in these distinct national fields? Broadly speaking, are there different schools of geographic thought which cut across national boundaries to some degree?

The introduction to such a composite study as is here outlined would seem to fall into two parts. Firstly it is necessary to give a brief survey of the development of geography in the last fifty years—though this will be covered in greater detail in many of the later chapters; and secondly it will be helpful to explain how the choice of the varied topics discussed in the score of chapters was arrived at. Needless to say no final answers can be given to all the questions posed above; but it is hoped that the authors involved will cover most of the fields in question, and their personal views will be advanced in their chapters. It is natural that the authors will take opposite sides in certain problems; as for instance in the broad question of Possibilism versus Environmentalism. The reader himself must be the judge as to which attitude in such cases seems to be the most rational. Certainly the editor has not tried to modify the conclusions of any writer; and indeed he is himself quite willing to be classed as one of those geographers who is to some extent tarred with the determinist brush.

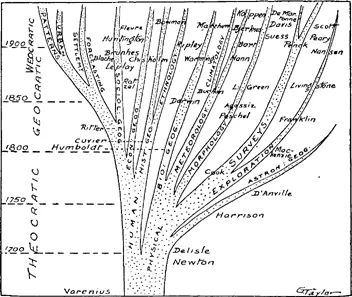

It is often useful to adopt the heuristic approach in discussing a somewhat complex problem, i.e. we may examine the path followed by the pioneers in geography. In Fig. 1 a much generalized diagram illustrates the evolution of the various ramifications of geography in the early days of the subject; and some brief reference is made to those eminent workers who have done so much to advance our study. We may rapidly pass over the studies of classical and medieval times when many essays and books appeared in which the question ‘How do the people live?’ was answered more or less adequately, so that the study was almost purely descriptive. In the sixteenth century or thereabouts the development of cartography was so far advanced that a fair answer could be given to the question, ‘Where do the people live?’ It was not however till about 1770 that the invention of the chronometer by Harrison enabled this localization of places to be carried out with any accuracy. Accurate world-maps appeared for the first time after longitude could be ascertained with some exactitude as in the famous maps of Delisle and D’Anville.

FIG. 1.—The Ramifications of Modern Geography since 1700. Note the shift from exploration to urban patterns

Great navigators such as Cook and La Perouse added some of the last coastlines to the continents during the latter years of the eighteenth century. Franklin and Livingstone were two of the many who penetrated the unknown interior lands in the earlier years of the nineteenth century, and it is in this period of our history that modern geography had its beginnings. In the diagram (Fig. 1) I have suggested, by the thinning of the ‘branch’ concerned, that the essential principles of ‘astronomical geography’ were known by about 1800. This is not to say that much work has not been done since that date, but it is not so new or fundamental as before 1800. So also the next branch ‘exploration’ is shown to be dwindling in importance, since today—apart from the heart of Antarctica—there is no large area of the lands which is not charted in some detail.

We may I think agree to call Humboldt ‘the father of modern geography’. He travelled through Central and South America from 1799 to 1804, while in 1829 he traversed Russia and Siberia. He described his travels and discoveries in some forty scientific volumes. He was the first to plot world isotherms, and to demonstrate man’s dependence on his environment. He thus developed what I have been accustomed to call a ‘Geocratic’ type of geography, which suggests that the earth (i.e. Nature) itself plays a great part in determining the type of life which develops in a particular area. No biologist would deny this, but many modern geographers seem disposed to deprive Nature of almost all claims as a factor in such matters.

Of course during the Middle Ages there was a strong tendency towards a teleological slant in all sciences, as was expounded by Roy and Butler (1736). In their opinion, an all-wise providence arranged matters with a view to the well-being of that privileged biped, homo sapiens. This point of view we may term the ‘Theocratic’ aspect; and it was by no means wholly displaced by the disciples of Humboldt. Thus we find the historian Ritter (about 1820) using Humboldt’s data in many of his books, which however had this theocratic slant. Guyot of Princeton advanced similar ideas as lately as 1873! It is perhaps not going too far to say that even today, when Nature and the environment in general is receiving such a drubbing at the hands of the ‘Possibilists’, who stress what one may term ‘We-ocratic’ control, the theocratic approach is not altogether a tiling of the past.

The second half of the nineteenth century was marked by the intense interest in evolution in plant, animal (and human) life. Darwin and many of the early biologists of his time placed the greatest emphasis on environment and environmental changes. It would be surprising if the young geographic science was not strongly affected. Accordingly we find Ratzel (1844–1904) developing the ‘geocratic’ or environmental approach very strongly in Germany. This emphasis on causes was very characteristic of this period, and it was now possible to answer with some degree of accuracy the question ‘Why do people live as and where they do?’

The term ‘geography’ has been in use since the early days of the Greeks. At first it naturally included all aspects dealing with description of the earth and its parts. But gradually daughter disciplines branched off from the parent stem. (For instance the term ‘geology’ was used about 1690 by Erasmus Warren in a book dealing with the Earth before the Deluge.) As our diagram suggests it is possible to separate the physical and human aspects of the subject to some extent, and most of the purely physical aspects are moving further and further away from what is now accepted as the ‘core of geography’. Accurate surveys are so elaborate today that they are taken over by specially trained surveyors and engineers. Meteorology, with its close affiliation with dynamics and other branches of physics, is still close to the borderland of geography; but was definitely included in geography with its sister climatology a few decades ago. So also geomorphology has a liaison position, some claiming it as essentially geology, others as geography. The new science of geophysics seems to have little liaison with geography, but to he halfway between geology and physics.

Perhaps we may date the rise of a definite Human Geography towards the close of the nineteenth century. Ratzel published his Anthropogeography in the decade 1882–91; but in spite of the title, he gave little power to the human factor in his relation of nature and man, and was most definitely a determinist. Meanwhile the purely human aspects were being very closely studied by the early sociologist Leplay about 1855, and we see here another science (sociology) branching from the common geographical trunk. It was natural that sociologists and anthropologists (who perhaps may be dated from Prichard in 1843) should object strongly to the small part played by man in the world scene as discussed by Ratzel. Especially would economists and economic geographers object to any belittlement of man’s work on the earth. The latter school became prominent about 1862, when Andrée’s Geographie des Welthandels was first published.

At the beginning of the twentieth century geography was on a firm footing in Germany and France, for Ritter held a chair at Berlin before 1870, while by 1886 there were twelve professors in Germany and about the same number in France. At Oxford the first University teacher was appointed in 1887 and at Cambridge in 1888. The United States lagged behind somewhat, and the first Professor of Geography was appointed in 1900. The present writer occupied the first independent chair in Australia in 1920, and the first in Canada in 1935.

Fundamentals of Geography

In a later chapter Dr. Tatham deals with the rise of a determinist outlook in geography. The conclusions of the early unscientific determinists—such as Buckle—were erroneous because they had no accurate data as to the environment, i.e. the climate, structure, geology, soils, &c. Moreover they dealt with the effect of environment on intangibles such as character and temperament. Even today such relations are quite uncertain. Very different is the picture now with regard to material progress.

The modern scientific determinist has an entirely different technique, and he knows his environment. Thirty years ago I predicted the future settlement-pattern in Australia (Fig. 55). At Canberra (in 1948) it was very gratifying to be assured by the various members of the scientific research groups there, that my deductions (based purely on the environment) were completely justified. This aspect of geography is Scientific Determinism.

In every branch of science we find specific differences developing as organisms spread into different environments. This is true in regard to the outlooks of exponents of geography in different parts of the world. Thus geographers in France, Germany, and England were dealing with areas for the most part fairly completely occupied by man. They were blessed with adequate detailed maps long before this was the case in such lands as the United States, Australia, or Canada. As a consequence there developed about the turn of the century a somewhat different feeling as to the main purposes of geographic research in the two contrasted areas, the Old Lands and the New Lands.

Vidal de la Blache taught in Paris from 1877 to 1918, and he developed the concept that the environment contains a number of possibilities, and their utilization is dependent almost entirely on human selection. This concept gave rise to the school of Possibilists. He realized the necessity for detailed synthetic studies in geography; and through his inspiration a number of regional monographs were published in the last decade of the last century. It is very important to understand that la Blache was dealing with the land of France—which some geographers are willing to accept as the best environment for all-round human development to be found on earth. What was the natural result of this environment, and of the plenitude of detailed maps of all parts of the country? Surely enthusiasm for the detailed study in the minutest particulars of all aspects of the human habitat, and the growth of a firm belief that man played the chief part in the development of the region.

Another somewhat psychological factor comes into play here too. Although the emphasis on regional studies was soon stressed in Germany, yet the latter had been the birthplace of Ratzel’s determinism. It is probable that there was a slight tendency of French geographers to swing to the other extreme and support very strongly the new ‘regionalism’. To sum up we may say that a somewhat determinist approach fostered by the great advances made in the knowledge of evolution, was the characteristic of the latter part of the nineteenth century; but that in Europe in the next half-century the popular point of view, following Vidal de la Blache, Brunhes (and in Germany Hettner and Passarge) was the regional and possibilist outlook on geography.

What was the state of affairs in the first of the New Lands to develop a geographic outlook? Here in U.S.A. the population in 1900 was just half of what it is today, and the law of diminishing returns had hardly begun to operate. The greatest names in fields allied to those of geography were geologists such as Gilbert, Powell, Agassiz, and later William Morris Davis. It has been pointed out that early publications of the American geographers around 1900 consisted largely of morphological research, and regional studies were almost unknown. In those happy days the geographer discussed the structure and climate of a country, and then proceeded to show how man had spread through the land in response to these major environmental factors. Ratzel was honoured and Ellen Semple was his prophetess.

However, a younger generation of geographers was soon occupying the chairs of the main teaching institutions. As ever, as new ideas appealed to many of them, and accurate maps accumulated and detailed research was possible, the disciples of the possibilist and regional school became more and more numerous. The concept of the ‘cultural lands...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Part I Evolution of Geography and Its Philosophical Basis

- Part II The Environment as A Factor

- Part III Special Fields Of Geography

- Index