- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Changing Resource Problems of the Fourth World

About this book

Climbing food, fertiliser and mineral prices as well as the Arab oil embargo in the seventies had severe economic consequences in developing countries. Originally published in 1976, this study explores the effects of these developments in the fourth world and how they can adjust to an international economy with a particular focus on resource availability in terms of energy and agriculture. This title will be of interest to students of Environmental Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Changing Resource Problems of the Fourth World by Ronald G. Ridker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Économie & Économie de l'environnement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ÉconomieSubtopic

Économie de l'environnementIII. DOMESTIC ADJUSTMENTS AND ACCOMMODATIONS TO HIGHER RAW MATERIAL AND ENERGY PRICES

The sadden and unexpected increase in the price of oil and its products and the more gradual increase in the price of several raw materials have created serious imbalances which call for urgent domestic and external adjustments in all developed and developing countries. This paper attempts to briefly survey the extent of the increase in energy and raw material prices insofar as they affect the developing countries, to identify the likely effects of such price increases, and to examine the feasibility of domestic adjustments in these countries. It is difficult to discuss these issues with any degree of specificity because of the variations in the relative affluence (or poverty) of the developing countries, the diversity of their resource endowments, the wide variations in their technological capabilities and the uncertainties regarding future oil and other raw material prices. The discussion is therefore vague and generalized and is meant only to stimulate further examination of these issues.

Nature and Magnitude of the Problem

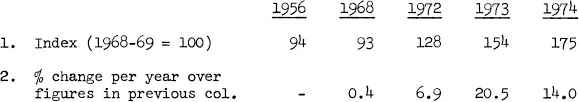

The examination of the impact of increased prices of oil and raw material must be seen in the context of the increase in the prices of other goods. The increase in international prices became a major issue at the turn of the decade and started - although in a relatively low key - with the inflation in developed countries. “It began before the rise in the prices of petroleum and other primary commodities and it is only partially explained by them.”1 The prices of capital goods and manufactured goods exported by developed countries, which rose less than 6% in the decade of the sixties, have risen by more than 10% annually since 1970. (See Table 1).

TABLE 1

Index of Export Prices of Developed Countries1

Source: Robert McNamara; Address at the Fund Bank Annual Meeting, IBRD, Washington, Sept. 1974

1 Note: An index of capital goods and manufactured export prices of major developed countries. The index also reflects changes in exchange rates.

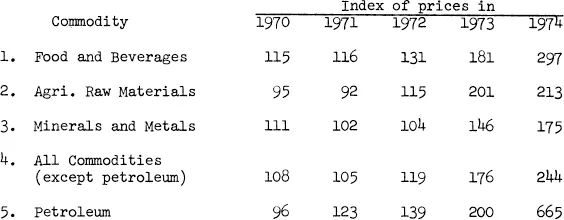

The prices of primary commodities, which constitute the major exports of developing countries, showed remarkable stability until 1971, but started to increase steeply from then on. As shown in Table 2, the price of petroleum, which moved slightly ahead of the prices of other primary commodities, showed a very steep increase in 1973 and further steep increase in January 1974.

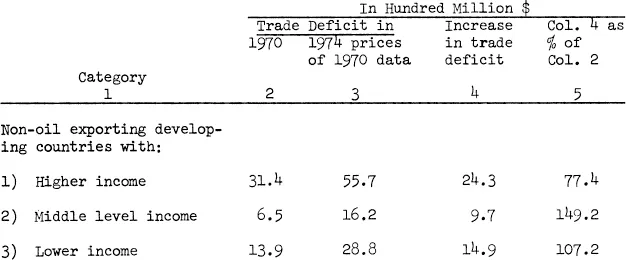

An analysis of the effects of such violent price changes on the developing countries would involve the determination of the price changes country by country, the changes in the volume of trade, the changes in the commodity composition of trade and the likely changes in the distribution of trade between the developed and developing countries as well as the distribution among the developing countries. A study2 of the hypothetical impact of the price changes between 1970 and 1974, applied to the country by country trade data of 1970 (without making allowances for the change in the volume and commodity composition of trade from 1970 to 1974), indicates that the trade balance of the developed countries changes from a deficit of $ * 8.4 billion to $ 82.1 billion - i.e., from 3.6 percent to 17.5 percent of their imports. The developing countries, whose trade was in near balance in 1970, show and increase in their trade surplus of $ 60 billion, which is about 37 percent of their exports. But the entire increase in the surplus of the developing countries (and more) accrues to the oil-exporting developing countries. These show an increase in trade surplus from $ 8.6 billion in 1970 to $ 66.8 billion in 1974. The deficit in the trade balance of the non-oil-exporting developing countries** registers an increase from $ 8.5 billion to $ 17.4 billion. (30 percent of their imports in 1974 prices.) Even this order of increased deficit in developing countries is considered to be an underestimate. Studies 3,4 which allow partially for the changes in trade in volume and commodity composition beyond 1970 indicate that the likely trade surplus of the oil-exporting developing countries and the trade deficit in the non-oil exporting developing countries would be somewhat higher.

TABLE 2

Index of Export Prices of Primary Commodities 1967-68 = 100

Source: IBRD-IDA - Additional External Capital Requirements of Developing Countries, Washington - March ’74

In order to make the analysis more meaningful, it is necessary to disaggregate the developing countries into sub-groups and analyze the impact of increased energy and raw material prices on each sub-group. Although it is possible to effect such disaggregation in terms of the developing countries’ endowments of resources (particularly energy and mineral resources), their relative technological capabilities, or the variations in their GNP, for the purpose of this paper, the developing countries are classified into four categories as follows:

1. Oil exporting developing countries.

2. Other developing countries with higher income:

per capita GNP above $ 340 in 1970.

per capita GNP above $ 340 in 1970.

3. Other developing countries with middle level income:

per capita GNP between $ 200 and $ 340 in 1970.

per capita GNP between $ 200 and $ 340 in 1970.

4. Other developing countries with lower income:

per capita GNP below $ 200 in 1970.

per capita GNP below $ 200 in 1970.

A representative selection of countries in groups 2 to 4 was made and the effects of the price increases on their trade balances were examined. The countries selected and their populations are set out in the Annex to Table 1.

On the basis of the sample chosen, as shown in Table 3, higher income group countries have been the least affected among the other developing countries while the middle level income group countries have been the most affected.

TABLE 3

Increase in Trade Deficit Between 1970 and 1974 of Selected Developing Countries

Source: For Col. 2 and 3, as computed and set out in Annex Tables II & III.

Possible Responses

The increase in trade deficits could be balanced either by inflows of capital resources from other countries, by an increase in the terms of trade, or by adjustments in production, consumption, and trade plans. If the prices of the exports of the “other developing countries” could be increased immediately to levels which would neutralize the increase in the prices of their imports, the problem could be solved at once. If the terms of trade improve gradually in the next few years, the problem of increased prices will become a transient one and can be tackled by domestic adjustments. But if the 1974 terms of trade continue throughout the foreseeable future, domestic adjustments of a more enduring kind must be made. The single most important factor determining the nature of the response of the other developing countries to the increased price of oil and raw materials is their perception of the terms of trade that will face them in the coming years.

Terms of Trade

The major export commodities of the “other developing countries” are minerals and agricultural raw materials, the demand for which is a function of industrial activity in the developed countries, and tropical agricultural consumer products (such as sugar, coffee and cocoa), the demand for which is dependent on the level of consumption in the affluent countries. Among these export items, natural products like rubber and jute, which compete in the international market with petroleum-based chemical substitutes, can be expected to benefit directly from the oil price increase. But prices of other agricultural raw materials and minerals depend on the level of industrial activity in the developed countries, and the new demand generated in the oil exporting countries. All indications are that industrial activity in the developed world will not increase at the rapid rate witnessed in the last decade. The rate of growth of the GNP in the OECD countries, which was 5.8 percent in 1972 and 8.7 percent in 1973, is now anticipated to be only 4.8 percent per year5 until 1980 - even this is considered a “relatively high rate estimated to ensure that the energy requirements are not understated.” The year 1974 has ended with unmistakable signs of a significant slowing down of industrial activity in the USA, Japan, and most countries of Western Europe. Unless the countries exporting minerals and agricultural raw materials organize collective action, the prices of these commodities may come down. While the increased affluence of the oil exporting countries will increase, the demand for tropical products such as sugar, coffee, and cocoa, the resulting demand increase will not be so high as to affect the prices significantly. In sum, there is no indication, based on purely economic considerations, that the terms of trade of the other developing countries will improve significantly after 1974. In fact, a more detailed analysis of the medium term price trends to 19806 leads to the conclusion that the terms of trade are likely to deteriorate further, as outlined in Table 4.

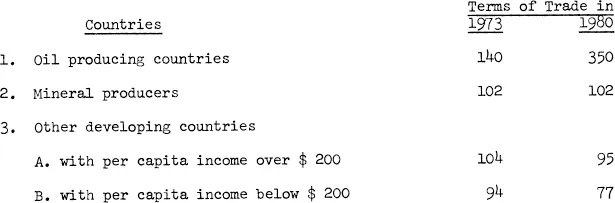

TABLE 4

Terms of Trade of Developing Countries in 1973 & 1980 (1967-68 = 100)

Source: Robert McNamara: Address at the Fund Bank Annual Meeting, IBRD, Washington - September 1974

Transitional Adjustments

If the terms of trade do not improve for the other developing countries, there will be a net outflow of resources from these countries amounting to at least $ 10 billion, about 3 percent of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This must be financed by reductions in consumption or investment. Such reductions can be avoided temporarily by drawing on reserves, or it can be postponed by the flow of capital from other countries to the developing countries by way of commercial borrowing, foreign investment, or aid.

To what extent will it be possible to effect these temporary adjustments? The “reserves” of the other developing countries amount to $ 32 billion, or about 37 percent of their imports in 1970. Nearly 50 percent of these reserves are in the higher income developing countries, and they alone can draw upon their reserves for any significant amounts. The average borrowing in the bond markets of the world by the developing countries increased in the early seventies and is more than $ 6 billion a year at present. But here again a substantial portion of the borrowing is done by the higher income countries and a few middle income countries. The official Bilateral Development Assistance (BDA) disbursed to the other developing countries during 1969-72 has been on an average of only $ 3.6 billion annually; over 50 percent of this was for the lower income countries. Among the developing countries, the higher income group may be able to step up their withdrawal from reserves and their level of commercial borrowing, but the countries with relatively lower income will have to depend on development assistance. Unless the oil-exporting countries, which have a sudden increase in their surplus, recycle the same to the lower income developing countries through bilateral negotiations or through appropriate intermediaries, the lower income developing countries may not be able to effect even the temporary adjustments.

However, the capital flows by themselves are unlikely to provide a lasting solution to the problem. Higher costs of energy and raw materials will have to be paid for either by an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- I. Introduction

- II. The Relative Bargaining Strengths of the Developing Countries

- III. Domestic Adjustments and Accommodations to Higher Raw Material and Energy Prices

- IV. Energy Use and Agricultural Production in Developing Countries

- V. Energy and the Less Developed Countries: Needs for Additional Research