![]()

Chapter 1

A productive conflict

The Colosseum and early modern religious performance

Mårten Snickare

The importance of Antiquity for the political and cultural life of early modern Rome can hardly be overestimated. Scholars, antiquarians, collectors, dealers and forgers were absorbed in the textual and material remains of ancient Rome; artists and architects turned to the ancient sculptures and buildings as models and touchstones; aristocrats looked at Roman Caesars and commanders as role models; people from all over Europe travelled to Rome to experience the ancient marvels.1

However, this intense preoccupation with Antiquity was not without tensions. After all, the Caesars and citizens of ancient Rome had been heathens, worshipping false gods. While on the one hand admiring, and building on, the splendour of ancient Rome, on the other hand the early modern papal city also felt a need to display its triumph over the pagan past. Ancient buildings and other remains were not only revered and admired, they also became subject to reconceptualization and physical transformation. The Pantheon, originally a temple to all the Roman gods, had already been converted into a Christian church in the seventh century. Next to the Pantheon, the gothic church of S Maria Sopra Minerva by its very name called attention to the fact that it was built directly on the foundations of a temple to Minerva – thus both supported by, and triumphing over, the Ancient heritage. A similar case is Trajan’s column, one of the most admired and well-preserved ancient monuments in the city. In 1588 Pope Sixtus V commissioned a colossal statue of St Peter to be placed on top of the column, in the place where there was originally a statue of the triumphant emperor.2 Still in its place, the statue of the first pope is thus literally exalted by the firm foundation of Antiquity while, at the same time, triumphing over it.

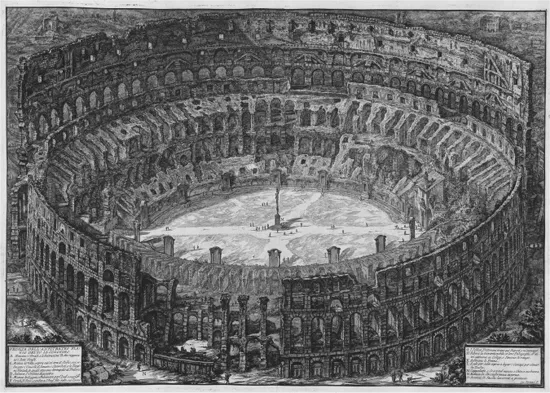

Figure 1.1 Giovanni Battista Piranesi, ‘Veduta dell’Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo’, etching in Vedute di Roma, 1776 (© and photo: National Library of Sweden)

Matters were brought to a head at the Flavian Amphitheatre, or Colosseum (Figure 1.1). On the one hand it was the most remarkable remnant of ancient grandeur, the foremost landmark of the city and the obvious architectural model to imitate and emulate. On the other hand it was the stage for the most brutal persecution and execution of early Christian martyrs.3 The Colosseum could thus be described as the site where the two grand narratives of Antiquity and Christianity clashed.

This chapter shows how the ambivalent status of the Colosseum in early-modern Christian Rome made it a most striking and productive stage for religious ceremonial; how the emotional intensity of the religious performances was heightened by the sublime ruin and the gory narratives it evoked; and how the Colosseum in its turn was transformed, physically as well as conceptually, by the performances. I will further show how the productive conflict between Antiquity and Christianity was dramatized in a ritual interplay – or kind of paragone – between the Colosseum and St Peter’s, centre of the Catholic Church.

The Colosseum, the largest amphitheatre of the Roman Empire, was constructed between 72 and 80 AD, under the emperors Vespasian and Titus.4 With room for 50,000 seated spectators it was a stage for gladiator and animal fights as well as other public spectacles, such as mock sea battles, mythological dramas, and executions. In the sixth century, after five centuries of use, it was closed to the public due to disrepair. The collapse of the outer walls of the southern part in the eighth century gave the ruin more or less its present shape.

Already in the Middle Ages, papal interest in the Colosseum can be observed.5 The still-standing northern façade provided a magnificent backdrop along the main papal processional route between St Peter’s and the Lateran, its preservation thus becoming a concern for the popes. At the same time, the very same popes made use of the ruined southern part as a stone quarry for the erection of new churches and palaces. Long regarded by scholars as an act of disrespect for the ancient monument, this practice might instead be understood – as art historian David Karmon has recently suggested – as an expression of the great value that came to be attached to it. Stones from the Colosseum were treated as relics which carried with them the grandeur of Ancient Rome as well as the blood of Christian martyrs. An interesting example is the papal Benediction Loggia, built in front of the old St Peter’s in the mid fifteenth century. Pius II explicitly ordered stone from the Colosseum for the construction of three superimposed arcades, stylistically recalling the shape of the amphitheatre. Karmon suggests that we interpret this as a way of resurrecting the fallen arcades of the Colosseum in a prominent new location.6 Arguably, a link was thus created between the ancient amphitheatre and St Peter’s, the centre of the Catholic Church. This link would be further elaborated and strengthened in seventeenth-century papal ceremonial.

Passion plays

In the late fifteenth century, almost a thousand years after the last gladiator fights, the Colosseum again became a stage for grand public spectacles, as the Confraternity of the Gonfalone received papal permission to use the ruin for Passion plays in Easter week.7 From 1490 to 1539 the Confraternity regularly staged lavish plays with elaborate stage settings and numerous actors and musicians, attracting large audiences. The revival of the Colosseum as a performance venue had direct repercussions on the physical shape of the monument: a new circuit wall around the arena replaced the vanishing traces of the original wall, and new seating was installed. In that way, the adaptation of the ancient ruin to fit the religious performances also involved a partial reconstruction of its original shape.8

The Confraternity’s choice of venue for the Passion plays was anything but arbitrary. The legends of Christian martyrs who had been brutally butchered in the arena served to heighten the emotional effect of the performance of Christ’s suffering and death, while the staging of Christ’s Resurrection against the backdrop of the ruinous building formed a strong image of the triumph of Christianity over the pagan past.9 That an early modern audience was sensitive to this interplay between Antiquity and Christianity is suggested by the following quotation from the travel journal of the German pilgrim Arnold von Harff in 1497:

Item in dieser stat lijcht eyn gar schoyn alt pallais ad coliseum geheysschen, is van en buyssen ront off gemmuyrt mit vil kleynen ghewulfften eyn boeuen deme anderen ind bynnen is eyn wijdt ront playtz dae maich man an allen eynden off dit pallais gayn myt steynen trappen. Man saicht uns dat vurtzijden die heren eyn boeuen deme anderen gestanden weren off den trappen, dae hetten sij zo geseyn off dem platz triumpheren strijden vechten ind wylt gedeirs sich zo samen Kempten. Item off desem playtz in dem alden pallays saegen wir off den guden vrijdach unsers heren Ihu passie spleen ind dat gynck allet zo mit leuendichen luden, as dat geysselen crucigen ind wye sich Judas erhangen hatte.10

[In this town is also a very beautiful ancient palace, called the Colosseum, built round in shape, with many smaller arches and vaults and, within it, a large round piazza, surrounded on all sides by stone steps by which one may ascend to the palace. We have been told that in ancient times men were seated on these steps to see the fights against wild beasts. In this same piazza in the ancient palace we saw on Good Friday a Passion Play showing the flagellation and crucifixion of our Lord Christ, as well as Judas hanging himself.]

The explicit intentions of the Confraternity were to promote popular piety by appealing to the emotions of the spectators. They did so by every means available. During the torchlight procession through the city that preceded the play, members of the Confraternity flagellated themselves, their blood bathing the streets of Rome according to contemporary chroniclers.11 One can easily imagine how the blood of the flagellants merged in the imagination of the spectators into the blood of the tormented Christ and the blood of the martyrs who had been butchered in the arena. As the procession reached the Colosseum, an Angel appeared, introducing the play and warning the spectators that if they did not weep during the performance, they did not firmly believe in Christ.12

The success of the Passion plays in stirring the emotions of the spectators is suggested by the way the plays ceased. In 1539, the pope prohibited the use of the Colosseum for religious theatrical performances because of the strong excitement and uncontrolled violence aroused by the plays. It seems that the audience on some occasions had begun to stone the actors who played Jews and Roman soldiers, before running out of the amphitheatre to stone the Jews who lived nearby.13 Borders between performance and life outside the performance were thus transgressed in an outbreak of anti-Semitic violence carrying ambivalent symbolic undertones. On the one hand, the stones thrown at the Jews had formed part of the amphitheatre in which Christian martyrs had been executed in the same way as Christ, according to the violators, had been killed by the Jews. On the other hand, the very same stones had been cut and carried by Jewish war captives, taken by Titus at the conquest of Jerusalem and forced to work on his building projects.14

The history of Passion plays in the Colosseum is thus rather short. However, the performances played a crucial role for the reconceptualization of the Colosseum as first and foremost a sacred space, a site for the veneration of the early Christian martyrs, and of Christ.

Possessi processions

An occasion on which the clash between Antiquity and Christianity was acted out was the so-called possesso, the procession by which a newly elected pope took possession of the city of Rome. Ancient ruins and remains were incorporated in the processional staging as symbols of Antiquity and Christianity were juxtaposed, intertwined or contrasted wi...