eBook - ePub

The Evolving Structure of the East Asian Economic System since 1700

A Comparative Analysis

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Evolving Structure of the East Asian Economic System since 1700

A Comparative Analysis

About this book

This book is the fifth volume of essays edited by A. J. H Latham and Heita Kawakatsu from the International Economic History Congresses looking at the development of the Asian Economy. Bringing together leading scholars from both the east and west, this book offers fascinating insights into the cotton trade, the rice, wheat and shipping industries and the development of trade and finance in East Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Evolving Structure of the East Asian Economic System since 1700 by A.J.H. Latham,Heita Kawakatsu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

1 International

competition in cotton goods in the late

nineteenth century

Britain versus India and East Asia*

This paper is concerned with what seems contradictory phenomena observed in late nineteenth century Asia: the increasing export of British cotton goods to Asia on the one hand, with the development of the indigenous cotton industry in the region on the other. The inquiry addresses the following points.

A. Concerning the Asian markets at large:

One of the pivots of the world payments mechanism in the late nineteenth century, as Professor Saul and Dr. Latham demonstrated, was Britain's ability to maintain a deficit on her visible trade with industrial Europe and the U.S.A., a deficit which she balanced by means of a surplus with the undeveloped world in general and Asia in particular.1

This Asian surplus, on trade in commodities, accrued largely from exports of Lancashire's cotton manufactures to the Asian markets. Did this influx of British goods into the region have devastating effects on the cotton manufacturing industry there, as has been often assumed?2

B. With respect to the East Asian markets:

Immediately after signing the Treaty of Nankeen (1842) the British representative, Sir Henry Pottinger, promised his countrymen that a huge market, consisting of one third of the world's population had just opened up to cotton goods’ producers in Britain, and went so far as to say, “all the mills in Lancashire could not make stocking-stuff sufficient for one of its provinces.”3 The great expectation he entertained, however, never materialized. A British consul at Hong Kong stated in 1852, “it seems a strange result, after ten years’ open trade with this great country, and after the abolition of all monopolies on both sides, that China, with her swarming millions, should not consume one half so much of our manufactures as Holland.”4 Taking into account the sheer size of the population of East Asia, and also the fact that the peoples there traditionally wore cottons, the East Asian markets remained noticeably small for British goods. The estimated population of East Asia (China, Japan and Korea) was approximately 514m in 1880, whereas that of India was about 217m.5 India with a population less than half of East Asia, took about 40 per cent of the total British overseas export of cotton textiles in the last quarter of the century, while China and Japan, put together, absorbed less than 15 per cent of the total. What caused this sizable difference between them?

C. As regards Japanese competition:

When Japan opened her ports to foreign trade in 1859, her cotton industry was tiny compared to “the Workshop of the World.” Nonetheless, Japan became a net exporter of cotton yarn in 1897 and of cotton textiles in 1909, and as Professor Sandberg puts it, “indeed, even before World War I, Japan was the only serious threat to Britain in third markets.”6 How was this possible?

I. Textile markets: price and quality differences

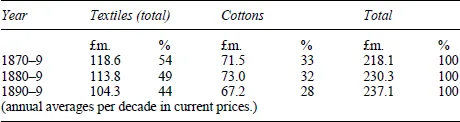

Cotton goods occupied the first place in total exports of late nineteenth century Britain, as Table 1.1 shows. When the export of the British cotton goods reached the other side of the globe, the cotton industries of India, China and Japan had developed to such an extent that cottons were the most essential clothing materials there. It was to these countries that British cotton goods were increasingly exported towards the end of the century (see Table 1.2). From these tables one may assume that there must have been serious blows inflicted upon the Eastern cotton industries. Indeed, as early as 1834–35, the Governor General of India reported, “the misery hardly finds a parallel in the history of commerce. The bones of the cotton weavers are bleaching the plains of India.”7 This passage quoted in Capital (the source unrecorded though) is often referred to as an archetypal example of the cheap machine-made cloth uprooting the native handicrafts.8 If this had been the case, China and Japan, being deprived of tariff autonomy under a cause of “free trade”, must have suffered a similar fate. Marx and Engels wrote in the Manifesto of the Communist Party, “the cheap prices of its (the bourgeoisie's) commodities are the heavy artillery, with which it batters down all Chinese walls.” Sir Harry Parkes reported at Yokohama in 1866, “this country (Japan) . . . can obtain clothing more cheaply from foreigners than from its own cottage looms. Under this aspect, Japan promises to furnish a very satisfactory market for British manufactures.”9

Table 1.1 Exports from the United Kingdom

Source: Peter Mathias, The First Industrial Nation (2nd ed., London, 1983), p.434.

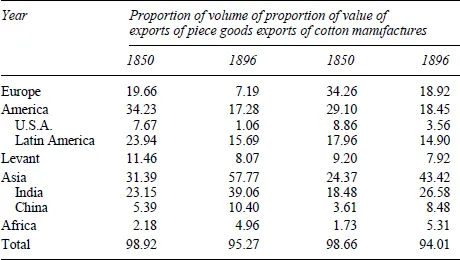

Table 1.2 Relative share of the main markets of the world in the exports of the British Cotton Industry, 1850–1896

Source: D.A. Farnie, The English Cotton Industry and the World Market 1815–1896 (Oxford, 1979), p.91.

Apparently, the above sort of view has placed much weight upon relative factor prices, assuming, in its simplest form, a state of perfect competition between British and Eastern textiles. It has yet to be proven, however, whether or not the British textiles were used as substitutes for native cloths, and therefore, were directly competitive in price.

An explanation as to why the Chinese market remained inconsiderable as compared with the Indian and also why British goods were virtually driven away from the Japanese markets, is that prices of British textiles were higher than native cloths. “The Japanese are almost universally clothed in cotton,” observed a British consul in the early Meiji period, and continued, “when English piece goods were supplied to them at a cost much below that for which they could obtain the produce of their handlooms, they were not slow to take advantage of them.”10 This line of argument, however, needs more careful examination, for no serious study has yet been made of textile prices. In the case of Chinese cotton textile markets, Professor Kang Chao summarizes the issue as follows:

It would be pointed out that none of the reports . . . has explicitly and systematically presented price comparisons between imported and local cloth. The price information from these reports is rather confusing. Mitchell implies that native products were lower in price; other reports mention that Chinese cloth was more expensive per unit but more durable too; at least one source suggests that the selling price was the same for both but native cloth was narrower . . . The Chinese literature, however, always claims that the imported cloth was cheaper.11

Bearing in mind the Chinese circumstances, it will be illuminating at this point in the argument to investigate Japanese cotton textile markets in more detail.

Meiji Japan's import of cottons changed the composition of her foreign trade. For the initial two decades after the opening of the country, Japan, along with other Asian countries, was a leading market for British textiles. But the following period from 1878 to 1890 saw cotton yarns become her major import, followed by raw cotton being the principal item of import after 1891.12 (This sequence, of course, reflected the development of the Japanese cotton industry.)

It can be argued, therefore, that, although Japanese cotton weavers might have been endangered by the imported British textiles during those initial two decades, the threat faded when the local weavers learned to use imported yarns as raw materials and supplied the domestic markets with their products. It is true that machine-made foreign yarns were 30 to 40 per cent cheaper than hand-made home yarns13, so that native weavers could have undersold the British rivals. However, this has yet to be proved.

What has been overlooked by historians is a selection of price data for the leading varieties of British and Japanese textiles sold in Tokyo. The data is available from 1878. If the above argument is correct, the price of Japanese textiles, after that particular year when cotton yarn became the major item of imports, should have been lower than that of the British.

British cotton textiles imported into Japan consisted of many varieties such as shirtings, chintz, taffachelas, etc. In 1860, English shirtings formed 54 per cent of Japanese imports of cotton textiles, and remained the principal choice among imported cloths in the following decades.14 The bulk of shirtings was delivered at the port of Yokohama from which most of the goods were transported to Tokyo.15 Of all kinds of cotton textiles produced in Japan, unbleached cotton textiles amounted to nearly half the total production in the Meiji period, followed by striped and bleached cotton textiles; these three varieties formed nearly three-quarters of the total.16 Unbleached and bleached cotton textiles were termed “white cotton cloth” by the Japanese. The Aichi prefecture produced roughly 40 per cent of the total output of this variety, for which Tokyo was the major market.17 In other words, Tokyo was the principal market for both the leading British and Japanese varieties.

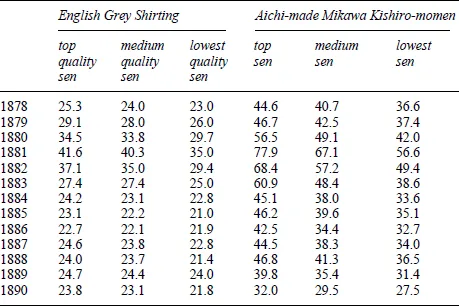

Since a roll of British shirting contained approximately eleven times as much as cloth as a roll of Aichi-made white cotton cloth, it is necessary to divide the prices of British shirting by eleven to obtain unit values. Table 1.3 is a summary of this procedure. The table indicates clearly, and contrary to the aforementioned contention, that Japanese textiles were far more expensive than British shirtings throughout the period concerned.

Table 1.3 Comparison of unit-values between British and Japanese cotton textiles sen per tan (100 sen = l yen; a tan = a cloth 34cm wide and 10.5m long, which provided just enough cloth to make a standard size kimono)

Source: Chugai Bukka Shinpo (Current Domestic and Foreign Prices, published weekly at Tokyo) for the period between 1878 and 1882; Tokyo Keizai Zasshi (Tokyo Economic Journal, published fortnightly at Tokyo) for the period between 1883 and 1890. The figures on the table are annual averages of prices which appear in these Journals at the nearest to the end of each month.

Regardless of the fact that Japanese cotton textiles were more expensive than the British rivals, the Japanese purchase of the latter declined as a whole, as Japan's import of cotton textiles fell from 5.5m yen in 1874 to 4.1m yen in 1890,18 whereas native cotton textile production rose from 10.5m yen to 31.9m yen during the same period.19 Concomitantly, the estimated per capita expenditure on textiles and clothes by the Japanese more than doubled during that period.20 The Japanese, therefore, preferred their domestic cotton textiles over the British ones despite the higher price of the former.

What is now at least clear is that an explanation in terms of price alone is not sufficient to explain the reason why British cotton textiles, in spite of their cheapness, did fail to permeate East Asia.

Although British shirtings, Japanese momen, and Chinese nankeen were all categorized as cotton fabric, careful scrutiny will show that the physical properties of British textiles were not the same as those of the latter two, hence their usage was not exactly alike. Some evidence suggests that British cotton textiles were passable substitutes for the native silk fabrics of East Asia. For example, a commercial ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Introduction

- PART I

- PART II

- Index