- 183 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

These two volumes bring together a wide variety of studies concerning the role nutrition plays in the etiology of various types of cancer, namely, cancer of the esophagus, upper alimentary tract, pancreas, liver, colon, breast, and prostate. The purpose of each chapter is to provide a critical interpretive review of the area, to identify gaps and inconsistencies in present knowledge, and to suggest new areas for future research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Diet, Nutrition and Cancer: A Critical Evaluation by Bandaru S. Reddy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Diet and Gastric Cancer

- I. Introduction

- II. Why Diet?

- III. The High Risk Diet

- A. Animal Fats and Proteins

- B. Abundance of Complex Carbohydrates

- C. Salads and Fruits

- D. Salt

- E. Nitrates and Nitrites

- IV. Etiologic Hypothesis

- References

I Introduction

There is a general consensus implicating diet as the main factor in human gastric cancer etiology. This concept has developed over the years and is based mostly on circumstantial evidence. There is, however, no scientific proof for it and no general agreement on the specific components of the diet supposedly responsible for gastric cancer.

Extensive reviews of the pertinent literature are available,1–4 Rather than repeating or updating such reviews, this chapter attempts to screen the relevant literature and select out those items which appear to have resisted the test of time and survived as viable candidates in the chain of events which may eventually lead to gastric cancer. Finally, their specific role in a proposed etiologic model will be considered.

II Why Diet?

Ingested materials are first detained and acted upon by digestive enzymes in the stomach. It is, therefore, not surprising that diet is considered a prime candidate for gastric carcinogenesis. Several mechanisms have been mentioned to explain the role of diet in gastric carcinogenesis: (1) presence of carcinogens in food; (2) introduction of carcinogens during food preparation; (3) absence of protective factors; (4) synthesis of carcinogens by interaction of food items; (5) irritants in food resulting in cancer promotion.2, 5

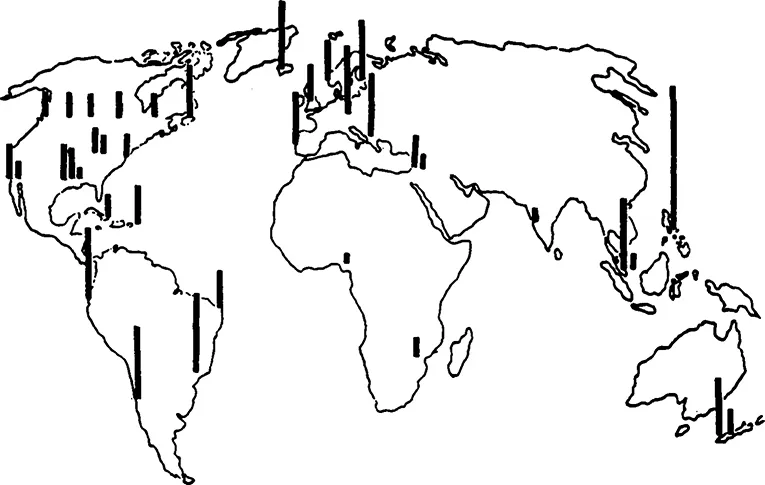

Some support for the speculation has been provided by the geographic distribution of the disease. Figure 1 is based on available data on gastric cancer incidence. The intercounty contrast is very prominent but geography by itself cannot explain why some subpopulations display risks several times greater than others inhabiting the same land. Chinese have rates several times greater than Malays in Singapore. Similar contrasts are observed between Maoris and whites in New Zealand; Japanese and whites in Hawaii; Indians and whites in New Mexico; blacks and whites in California; and Jews and Arabs in Israel.

In the contrasting situations mentioned above, racial and cultural differences exist between subpopulations inhabiting the same land. The role of race has been studied in migrant populations. Immigrants from high-risk areas to generally low-risk environment of the U.S. display slightly lower risks of gastric cancer in the first generation, but the second generation displays a dramatic drop in their risk.6 In some racial groups, like the Japanese, the risk reduction cannot be explained by interracial marriages. Similar experiences have been reported for immigrants to Austrialia, Canada, and Brazil.

Descriptive epidemiology studies, therefore, clearly indicate that race and geography are not the main determinants of gastric cancer frequency. Culture is strongly implicated. One of the main cultural differences between subpopulations at high and low risk is the diet. No contrast in gastric cancer risk is on record among populations with similar diet.

III The High-Risk Diet

Great diversity exists between the diets of populations at high gastric cancer risk. This probably explains why there was so much discrepancy in the results of the earlier dietary studies in several countries: rice was suspected in Japan, fried foods in Wales, potatoes in Slovenia, grain products in Finland, spices in Java, and smoked fish in Iceland.2 More recent studies have emphasized salty foods.7–9 The most remarkable trend, however, has been the realization that some old and some new studies are more prominently showing negative associations than positive associations.7–8 10–13 The analytical epidemiologic data, therefore, strongly point to the presence of protective factors in the diet.

Looking for common factors in the diet of high-risk populations and taking note of descriptive, correlational, and analytical studies, the “gastric cancer diet” has been characterized as follows:14

Figure 1 Diagram representing age-adjusted incidence rates of stomach cancer in different populations. (From Cancer incidence in Five Continents, Vol. 4, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, 1976.)

- Low in animal fat and animal proteins

- High in complex carbohydrates

- A substantial proportion of the protein is obtained from vegetable sources, mostly grains

- Low in salads and fresh, green, leafy vegetables

- Low in fresh fruits, especially citrus

- High in salt

An additional, somewhat controversial, item which should be considered is the presence of nitrates in the diet. The evidence implicating the above items is reviewed in the following paragraphs.

A. Animal Fats and Proteins

Most populations at high gastric cancer risk have diets low in animal fats and proteins. The protective effect of milk has been found prominently in Japan.7 Fat is needed for the proper utilization of lipid-soluble vitamins such as A and E, which may play a protective role. There are, however, many populations whose intake of animal fat and proteins is very low and still display very low risk of gastric cancer. Such is the case of most African aboriginals and most inhabitants of the tropical and subtropical lowlands, including most of Brazil and the Caribbean basin.

The evidence available cannot totally deny a possible role of low-fat diet in some situations but does indicate that other factors are needed to induce gastric cancer in humans.

B. Abundance of Complex Carbohydrates

The situation concerning this item is similar to the low-fat diet: it applies to most high-risk populations but it is equally prevalent in large populations displaying low risk. There appears to be a distinction, however, in the type of vegetables frequently consumed. In most situations high-risk populations base their diet on grains and roots which are subjected to involved cooking techniques. These populations are not inclined to eat fresh, uncooked vegetables. Not enough data exist to determine cultural differences between high- and low-risk populations with a predominantly vegetable diet. One recent study in Colombian rural villages found that a vegetable-based diet was predominant in all villages, but only the low-risk villagers were addict to fresh items (fruits and salads).14 The abundance of complex carbohydrates, therefore, is not a strong determinant factor in gastric carcinogenesis. The protective role of this type of diet in colon carcinogenesis is discussed elsewhere, but it should be mentioned here that large populations with high intake of complex carbohydrates have very low rates of both gastric and colon cancer: Brazil, Africa, and the Caribbean.

C. Salads and Fruits

The negative association between these items and gastric cancer is one of the most consistent findings: old and new studies in populations of different race and culture coincide on this point. Stocks reported it in England in 1933;15 Dunham in 1946, Haenszel in 1958, Higginson in 1959, and Graham in 1972 in the U.S.;11,16–18 Meinsma in Holland 1964;1,3 Hirayama in Japan in 1963;7,19 Paymaster in India in 1968;20 Bjelke in Norway in 1970;21 and Haenszel in Hawaii in 1972.8 The specific kind of fresh fruit or vegetable associated with low risk varies according to cultural dietary patterns, but it appears obvious that some common factor or factors exist in many fresh fruits and vegetables that may play a protective role in gastric carcinogenesis. The search for the common factor has led investigators to estimate the intake of micronutrients based on their concentration on specific food items, the usual size of a typical serving of each food item, and the frequency with which the item is reportedly eaten by cases and controls. The result of these calculations is usually expressed as an “index”.22 Such indexes may be adequate for hypothesis building but not for hypothesis testing because they are fraught with potential errors in the basic assumptions. Marked differences in the concentration of a micronutrient in a specific food may result from soil composition and fertilization patterns: the concentration of vitamin C in grains is considerably greater when in soils ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- The Editors

- Preface

- Contributors

- 1 Diet and Gastric Cancer

- 2 Diet and Cancer of the Pancreas: Epidemiological and Experimental Evidence

- 3 The Epidemiology of Large Bowel Cancer

- 4 Diet and Colon Cancer: Evidence from Human and Animal Model Studies

- 5 Nutrition and the Epidemiology of Breast Cancer

- 6 Dietary Fat and Mammary Cancer

- 7 The Role of Essential Fatty Acids and Prostaglandins in Breast Cancer

- 8 Diet and Cancer of the Prostate: Epidemiologic and Experimental Evidence

- 9 Dietary Fat and Cancer Risk: The Rationale for Intervention