![]()

Chapter One

LATIN AMERICA: AN EDUCATIONAL PROFILE

Colin Brock

Latin America was once portrayed by an eminent geographer as being a ‘harmony of contrasts’. Such a phrase could well be used to epitomise its educational character.

Unlike Africa and Asia - the other components of the so-called ‘Third World’ - Latin America has no clear cut geographical definition, though the major part of it, South America, is a continent in its own right. Most of Central America is a component of Latin America, though Mexico is occasionally included in definitions of North America. The islands of the Caribbean region, known as the West Indies, include parts of Latin America such as Cuba and the Dominican Republic as well as nations historically related more to Britain, France and the Netherlands than to Hispanic or Lusitanian metropoles. None the less, one international classification includes the entire Americas minus Canada and the USA in ‘Latin America’, and sub-divides the region into: Tropical South America; Temperate South America; Middle America; Caribbean.

Given that Latin America is generally regarded as being part of the ‘Third World’, the fact that many of the formal education systems of this region derive from the same formative period of national political development as do the major European systems is a significant consideration. The age of the emergence of nation states in Europe, deriving from the philosophical challenge of the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ is shared by the formation of many of the states of Latin America through their revolutionary wars of independence from Spain. Indeed, it is perhaps ironical that the contemporary external power in the region, the USA, emerged at much the same time and through a similar process, though primarily a colony and cultural offshoot of Britain rather than Spain. Herein lies the major division of the New World into Anglo America and Latin America.

So the nations of Latin America, while having been subject to European colonialism in its various forms like most other countries of the ‘Third World’, have a generic relationship with their European counterparts that differs from the European cultural overlay and colonial legacies in Africa and Asia. To many parts of Latin America the cultural dualism deriving from colonialism seems to be in respect of the long-standing paternalistic and economic influence of the USA rather than Europe. One must not forget, however, that the indigenous Amerindian peoples of Latin America were placed in a similar position in relation to European political economic and cultural domination as that experienced by Africans and Asians in their homelands. Nowadays of course, it is internal colonialism to which the Amerindians are subjected.

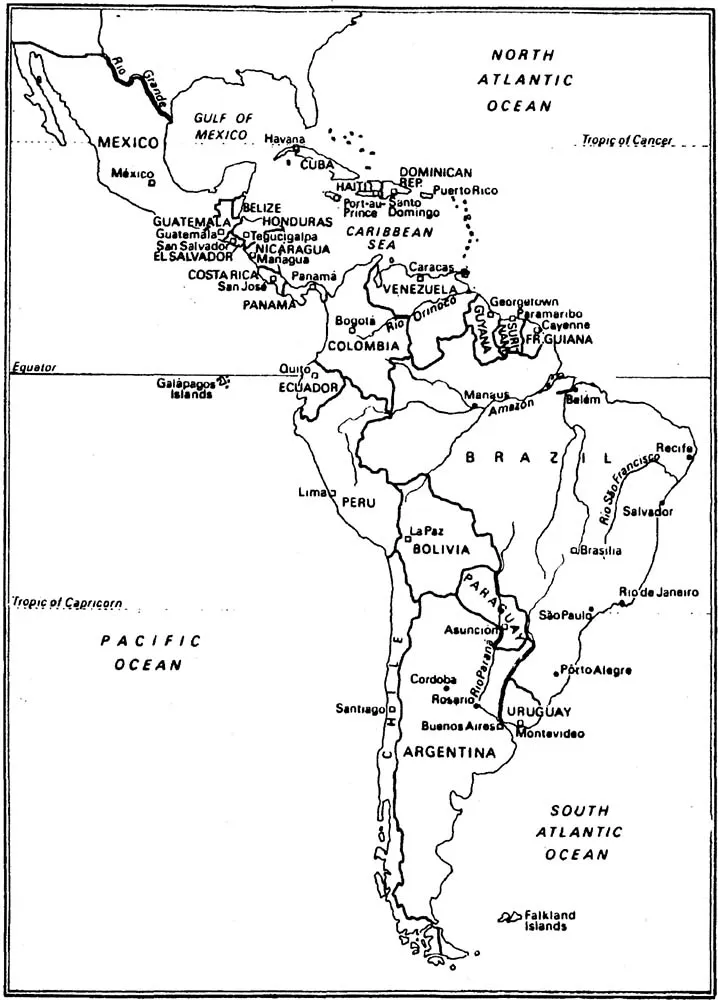

Fig. 1: Latin America

Source: adapted from Map 1 in: Wynia, G. W. (1984), The Politics of Latin American Development, Cambridge University Press.

Note: countries on this map not normally considered to be part of Latin America are: Belize, Guyana, Suriname and the Department of France known as French Guiana.

With few exceptions, the missions of the Catholic Church that accompanied and followed the Iberian conquest of the region, concentrated on the establishment of highly selective and academic educational foundations. Schools, seminaries and universities were central features of the towns and cities from which the colonial territories were controlled and administered. The rural/urban dichotomy in education, while a virtually global phenomenon, has particularly deep roots in Latin America. This is not just a question of human ecological context but also a structural feature. The formative influence on the nascent educational systems of the newly founded Latin American republics of the nineteenth century was that of Napoleonic France. Tiers of interlocked and hierarchical responsibility extended from national to regional to local scale of territorial administration, and in each of these levels from urban to rural. As a consequence of a combination of élitist educational philosophy, oppressive political control and economic constraint, the ideals of universal educational provision enshrined in the republican constitutions of Latin America have still to be realised in most countries of the region even at the primary level. Indeed, the incapacity of most of these systems, after about 150 years of political independence, in respect of servicing the mass of the population as well as the complex labour needs of national economies, provides a sobering example to younger developing countries with high expectations of education in terms of development.

During a century and a half, the history of educational development in Latin America has exhibited alternating phases of growth and retrenchment that have been remarkably concordant throughout the region. The periods of growth are characterised by an expansion of state provision under populist or socialistic governments, while in between, the private sector has been favoured by more conservative regimes. The nature of the policy does not seem to have related necessarily to the degree of autocracy, oligarchy or military control present during such phases, all three being common, almost endemic features of Latin American political history. The pattern has probably more to do with the strong influence on the region of the outside world in economic terms, and of the USA in particular. Despite the relatively early acquisition of political independence, the emerging economies of the Latin American republics were drawn into a position of dependency within the world economic order developed by the requirements of the industrialising nations of Western Europe, especially Britain. Although very little of the British Empire existed in Central and South America, British investment in and exploitation of the resources of the region was paramount in the nineteenth century. Along with this came a significant number of British professional, technical and entrepreneurial settlers, and the model of the English ‘public school’, still favoured by some Latin American elites. Large numbers of immigrants came also from other parts of Western Europe, and especially to the temperate zone comprising southern Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina and Chile. Some, especially the Germans and Italians were sufficiently numerous, culturally cohesive and influential to add new dimensions to the emerging patterns of educational provision.

The condition of dependency, whether political, economic or cultural requires not only external domination but also the collusion of the local élite. Given the generic relationship between the nation states of Europe and the emergence of the Latin American republics, it is not surprising that a condition of structural dependency was created, the study of which has provided the substance of dependency theory. The provision and operation of education has played a significant role in Latin American dependency, and continues to do so. Networks of political and cultural control emanate from the cities through a web of increasingly deficient school provision, with local political figures in general assuring the effective maintenance of the status quo. Local mayors are in effect caciques, keeping their power by negotiating between their populations and the agencies of municipal, provincial and national control for mutually acceptable ends. An example would be the provision of the means to construct or develop a village school in return for the acceptance of a particular teacher selected on grounds of politics or nepotism. A gradient of increasing incompleteness of even the primary sector descends from town, through village to the rural periphery, thus providing the educational dimension of the marginalisation of a significant proportion of the population of Latin America. This is the typical situation, deriving from a symbiosis of political neglect and environmental constraint, but there are other variants. For example, the so-called decentralisation mechanisms of some of the reactionary regimes of the present day, while promoted under a spurious liberal rationale are in practice a system to ensure the extension of central control of education. At the other end of the political spectrum, the equalisation of educational opportunity as between urban and rural sectors through massive investment in physical and human resources provides a government with a more efficient control mechanism, however altruistic the reform.

Clearly then, Latin American educational systems have been part of as well as influenced by the structures and dynamics of dependency. Since about 1920, however, the origin of the most influential external influences has shifted. The dominance of Western European nations, and especially Britain, over the Latin American economies was severely weakened by the action and aftermath of the Great War of 1914–18. Some states in the region succeeded to a degree in gaining greater control over their own economies by import substitution, diversification and industrialisation, but such developments were moderated by the increased influence of the USA and the onset of the world economic depression. Progressive educational trends inspired by Dewey’s thinking and destined to have influence world-wide, played their part in one of the expansionist periods of provision. In addition to providing additional schools, more imaginative innovations in areas such as adult and rural education took place and have continued to have some influence despite several alternations in the political climate in the meantime. One suspects that the ideas and operations of Paulo Freire and his successors in the adult literacy movement in Latin America owe more than a little to the vision of José Vasconcelos and his establishment of ‘Cultural Missions’ in Mexico in the 1920’s.

Although the World War of 1939–45, like its predecessor, provided a brief opportunity to Latin American states to diversify their economies and break loose from their structural dependency, it also saw the emergence of the USA as the undisputed leader of the nations of the world at least in economic terms. Given the historic Monrovian vision of that country as the guarantor of Western hemispheric freedom from Old World colonial oppression and infiltration, and the rise of the USSR to superpower status, the stage was set for a readjustment rather than a weakening of Latin American dependency. At the same time, the educational ideas of the newly founded United Nations Organisation, through its agency UNESCO, encouraged the provision of universal primary education in accordance with its Charter.

While the significance of a certain style of educational development for hemispheric solidarity under US patronage was not lost on the leadership of that country, the role of a different style of educational philosophy and investment was seen as crucial by those who sought to resolve the gross disparities and injustices of the human condition in Latin America through socialism. Within the context of the postwar economic boom, the USA launched the ‘Alliance for Progress’ which included massive projects of educational aid. These had the effect of a quantitative expansion of provision, but without challenging the long-standing structural inequities of the formal education systems of Latin America. Much of the improvement was in fact appropriated by the already privileged elites and middle classes who were in a position to determine the nature of increased educational provision. Unlike the mass of the population, they already enjoyed universal primary education and so priority was given to investment in the expansion of the secondary and tertiary sectors. Since access to these sectors is consequent upon successful completion of the primary programme, and for various reasons of deprivation and constraint only a tiny fraction of the masses achieve this, they have been effectively debarred from significant benefit. At the secondary level, the expansion accommodated increased enrolment of middle class females which in respect of the sexism endemic in Latin American societies did represent some sort of improvement. However, the tertiary sector gained most from the massive injection of public money into education, and the situation here was even more invidious. Entry to this sector has always been very competitive in Latin America, and one of the most important functions of private schooling has been to prepare for university selection. The consequence of expanding the tertiary sector has been to enable an increased proportion of the products of private schooling to enter. In general therefore, the educational outcome of largely US investment in increased provision has been to widen the gap between the privileged minority and the underprivileged majority in Latin American society. During the same period certain demographic trends have compounded the problem of educational provision for the masses. A continued high birth-rate in most countries of the region obviously places most strain on the already incomplete and underfunded primary sector, and massive migration from rural to urban areas often involving ‘illegal’ settlement adds a new dimension to the educational profile that most Latin American governments have hardly begun to cope with.

The Latin American republics came into being as revolutionary responses to the oppression and neglect of Iberian colonial rule. The general and educational ideals of this movement have been sustained by political radicals through the generations, and have from time to time enjoyed periods of implementation and innovation. One of the aftermaths of the Mexican revolution in this respect has been mentioned above. In the period since 1945 there has been first a phase when radical challenges to the structural inertia of Latin American educational provision gained some ground, and more recently a period of strong, often military reaction in favour of the traditional inequities. Given the extreme and in practice irrelevant nature of formal systems of state education in this region, it is perhaps not surprising that some of the most radical contemporary critics of this mode of provision, such as Ivan Illich and Paulo Freire, are Latin Americans. Their priorities lie not in formal schooling but in non-formal, adult and continuing education. Unlike the features of educational expansion under US funding, the combating of mass illiteracy has been a feature of regimes seeking to widen educational access and public awareness. Notably successful in this respect has been the Cuban revolution which has by most criteria sustained itself since 1959. Literacy campaigns have also been a priority of the more recent Nicaraguan socialist regime, and have enjoyed periods of support in various countries of the region, notably in Chile under Allende from 1970–73.

In general, however, education in Latin America remains under the influence of dependency and inertia, and exhibits today the same broad characteristics as 100 years ago. These are:

a. in most countries, incomplete systems even at primary level, despite their constitutional obligations, and the objectives of the Santiago Plan of 1963;

b. problems of enrolment at primary level, especially in the rural sector and in the barrios and favelas of the cities;

c. very high levels of repeating and wastage at primary level caused by inappropriate curriculum content and excessively strict examinations for promotion from one year to the next;

d. inadequate provision of public secondary schooling, except in the middle class sectors of the urban population, and even here the same sort of curricula and promotional problems as found at primary level;

e. a relatively large and thriving private sector serving the needs of the various elites and gaining a disproportionate share of university places;

f. a traditionally academic tertiary sector, which despite some diversification in recent decades remains in most countries insufficiently technical;

g. low teacher quality at all levels, especially in the rural sector, and a lack of professional status and identity for this occupation;

h. a strong correspondence between the quality of educational provision and the patterns of social class whereby the mass of the population is severely disadvantaged - this also tends to be linked indirectly with patterns of race and ethnicity thus producing multiple disadvantage for groups of non-European origin, mainly Amerindians and Blacks;

i. a poor correspondence between formal education and the occupational structure;

j. severe female disadvantage outside of the middle classes and elites;

k. increasing rates of illiteracy in most countries, with rural populations and females most disadvantaged in this respect.

There are of course exceptions where most or even all of these problems do not apply, notably Cuba and Costa Rica, or where genuine and vigorous attempts are being made to combat them, as for example in Mexico and Venezuela. But in much of the region the current phase of reactionary military regimes operating under a shared philosophy of ‘National Security’ is having the effect of increasing the inequities and disparities outlined above, as well as the operational role of education as a mechanism of social and political control. Whether the return of Argentina to a democratic system heralds a new phase, with the possibility of improving the educat...