![]()

1 Introducing smartphone cultures

Jane Vincent and Leslie Haddon

Smartphone Cultures aims to explore emerging questions about the ways that this mobile device technology has been appropriated and incorporated into everyday social practices. We have allowed some years for the smartphone to become embedded globally in the mobile communications market and for the apps market to mature before proposing this volume, during which time various authors have begun to construct a smartphone literature that first examined what people are doing with these devices (Chen 2011; Berry and Schleser 2014) and are now beginning to look more deeply at the cultural impact of these behaviours and activities (du Gay et al. 2013; Miller 2014; Donner 2015; Kobyashi et al. 2015). The volume covers a variety of different uses and experiences, in the hands of different users living in different contexts to see not only their practices, but what the smartphone technology means to them. We look at what the smartphone enables and some challenges it presents, and, indeed, at the aspects of life where it actually has little impact. We also examine the various attempts at institutional and individual levels to keep control of the technology, either because of general worries about the changes that it threatens, or as a way of dealing with the more mundane problems that the use of the smartphone can throw up in everyday life. No one volume can exhaustively cover a device that has such diverse potential, both in what it can do or support and by virtue of that, how it can be represented and evaluated. However, this book can and does aim to capture the multifaceted nature of the smartphone phenomenon, the different ways it can be analysed, how it can be framed, and identifies research questions for the future.

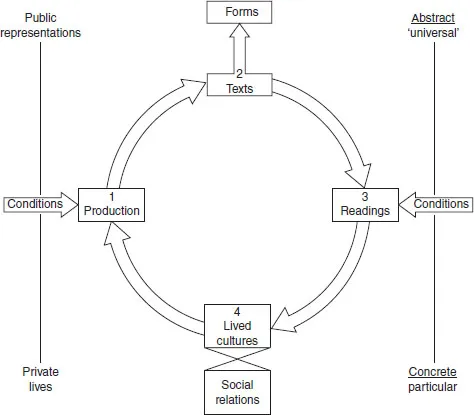

To bring some structure to this diversity, and have one overarching framework for the book, we specifically asked the authors to frame their work in terms of the cultural processes identified within the circuit of culture (Johnson 1986; du Gay et al. 1997).

In his book chapter, Johnson originally used this circuit, Figure 1.1, to identify the key types of cultural process studied in the relatively new subject of cultural studies and how these interlinked. To illustrate this Johnson provided the brief worked example of the Mini Metro car. He identified the ‘moment’ of ‘production’, which entailed not only the making of a material object, the car, but the making of meanings, what the car stood for. Once produced, as a ‘text’, it was open to further ‘readings’, further interpretations, where not only other commentators but ‘ordinary readers’, such as those who used the cars, could see the car in terms of the role it played in their lives, in their ‘lived culture’. Although not developed in Johnson’s text, we can take the example further noting how people used the car, and how they felt about it, could in principle be picked up in the next round of production, be that in terms of alterations to design or advertising copy. It is worth emphasising that this model was not about theorising a technology – this car was only a particular example of a ‘cultural form’. But the framework, that was really highlighting the questions that a researcher might ask, could equally apply to other cultural forms such as, citing Johnson’s own examples, a book, a television series or a public ritual.

Figure 1.1 Circuit of culture.

Source: Johnson 1986, p. 284.

Note

Pearson Education Limited Copyright. Reproduced with permission from the publisher.

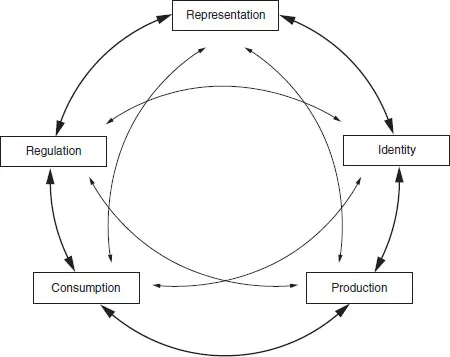

Some years later du Gay et al. (1997) drew on this approach using a variant of the original circuit, Figure 1.2, when exploring the ‘Story of the Walkman’. This new portable music playing device that appeared to be having a significant impact on society, for example raising new questions about the nature of privacy in public spaces long before the mobile phone was to do so.1 In their textbook aimed at UK Open University students du Gay et al. were, again, demonstrating the main types of cultural studies analysis that one could conduct using the worked example of the Walkman as a cultural form, as they clarified further in the second edition of the book (2013). But while they used the principle of the circuit, some of their terms and moments were slightly different. ‘Production’, somewhat similar to the Johnson version, remained, but the authors added ‘representations’ of the Walkman and ‘identity’ (here both in the sense of identifying with the product and the identity of the company producing the Walkman). Finally, in this version of the circuit we have ‘consumption’, covering the experience of the Walkman and what that can mean and symbolise for users and others, and ‘regulation’, the attempts to control usage of the technology because of the threats to social life that it represented. Du Gay et al. stressed that the original aim of their book was purely pedagogical, but acknowledged that it was in practice taken up across a variety of disciplines as a ‘research text’ (2013, p. xvi). We still find it useful for stimulating research questions.

Figure 1.2 Circuit of culture.

Source: Du Gay et al. 2013 p. xxxi [1997].

Note

Reproduced with permission from the publisher.

The general nature of the circuit model, either version, means that it is flexible enough to provide a framework for locating contemporary studies despite being designed nearly three decades ago. For example, under ‘production’ (which would draw on writers describing the industry such as Woyke 2014) we would also now have to take into account contemporary discussions of ‘prosumption’, and in the case of the smartphone the development of apps. Meanwhile the vision of Snickars and Vonderau (2012) would be an example of representations of what the smartphone means for society. Following Johnson, and du Gay et al., then, we will be using this model in the present volume to frame smartphone cultures, first to locate the chapters in this volume within existing smartphone studies but second, where possible, to use the framework as an aid to exploring what cultural processes could be researched in the future.

While smartphones might be in some sense ‘new’, which in turn makes the novelty of the technology attractive, the social and communicative affordances of the devices are themselves built on the back of previous products and user experiences. Hence, in addition to the circuit of culture, the smartphone would also have to be located historically and in this regard smartphones, and certainly the exponential growth in consumer demand for smartphones, even took industry by surprise. The adoption of its precursor, the mobile phone, was already growing globally at a phenomenal rate (Kakihara 2014) but the smartphone, with its access to the internet and thus much more information, communication and vastly greater multifunctionality, seemed to provide the foundation for potential cultural shifts that we are exploring in this volume. This very rapid and high-profile development itself led to some of the representations of the societal meaning of smartphones noted earlier. Yet, to put this technology into perspective, we also need to appreciate the smartphone is, in many respects, just one of the latest developments in a family of products or services which combine to deliver media and communications for consumers.

Then we have to consider the role of users in this historical process. Technology and industry-led developments in mobile communications delivered via increasingly sophisticated devices have contributed to the shaping of modes of social interaction, such as the mobile communication via social media applications. However, it is worth noting that innovations in this field have by no means followed a wholly industry-determined path. Indeed, in their choice of which information and communication products and services to adopt and adapt, users have already exerted some influence on the evolution of this field. For example, not all products in the run up to the smartphone have been successful, such as wireless application protocol (WAP) that aimed to deliver an early version of internet surfing. In contrast, and contrary to industry expectations, early innovations like Short Message Service, and Pay as You Go on mobile phones were pulled into the market by the degree of unanticipated consumer interest (Taylor and Vincent 2005). In this way users helped to shape future products, albeit while industry monitored the trends among and actions of their consumers and responded with new products. For example, teenage girls painting the back of phones in Finland led to coloured devices and decorated handset covers, or, personalised ring tones that in the early days of mobile phones were downloaded from a music library at Nokia HQ bespoke for each customer (Halper 2004) later became more standard mobile phone options. Thus, in this volume we would have to ask how user agency is now being expressed in relation to smartphones and how producers respond to this.

In order to understand some of the experiences, more particularly in our framework the ‘readings’, of this technology we also need to consider a different type of history. Accounts of the introduction of new technologies in the past (such as the telephone) highlighted the common occurrence of negative responses and even moral panics (Marvin 1990; Lasen 2005) sometimes entailing initial resistance to the threat of this ‘newness’. Hence it is important to appreciate a history of perceptions, or concerns, that underlie such reactions. For example, in this volume we capture how parental concerns about their children’s smartphone use do not only reflect a moral panic about online risks but also a long-standing discomfort – previously felt in relation to television, computers and electronic games – about the balance in their children’s lives being upset by the threat of too much screen time. Meanwhile one recurrent theme in recent generations has been that parents often feel less technologically expert than their children (Haddon and Vincent 2015).

Framed in terms of the ‘prosumers’ of this technology in the spirit of Toffler (1980), some analysts stress how a smartphone user is now able to combine and condense an exponential increase in multimodal social relations and media consumption. More celebratory accounts would argue that never before has anytime, anywhere, always on connectivity been more apposite for describing the opportunities for staying in touch, finding information, enjoying media and having instant connectivity. While there might be some truth in this compared to the era when PC access to the internet dominated, as well as exploring the agency of users, we would also need to explore the constraints on their experience of this technology, as will be particularly well demonstrated in this book in relation to children’s use.

In sum, in this volume we aim to provide a strategic assessment of smartphone use to unpack and explore its cultural impact on society and on individual users. Here the contributors have addressed smartphone culture not from the perspective of the technology’s potential but rather from the point of view of the actual influence of the affordances of smartphones and through the experiences, aspirations and concerns of or about its users. For example, we cover such dimensions as the ways in which people use or do not use smartphones for particular purposes because of how they want to represent themselves, or how parents sometimes restrict their children’s use because of fears about how the devices might affect their lives. Similarly, when discussing production we would want to think about how actual and anticipated practices of users are in turn incorporated by industry into the design of smartphone apps.

While as a personal device the smartphone has individualised and personalised qualities and functionality that differ from user to user, how it is used en masse in the day to day activities of contemporary society is examined in this book through the lens of various shared social practices of its users. This nuanced and often intimate approach demands an openness to theoretical/conceptual contributions that are flexible and broad enough to encompass the multitude of facets and interactions that using a smartphone entails. Also popular are theories of the presentation of self (Goffman 1959; Ling 2004) and domestication (Silverstone and Haddon 1996) that have been applied to previous studies of mobile communications; the social shaping of technology and users (MacKenzie and Wacjman 1999; Lasen 2005; Vincent 2006); the exploration of the affordances of devices (Gibson 1977; Goggin 2006; Schrock 2015), and mediatisation, which shows how aspects of society are intertwined with technological processes and the texture of social life (Harper 2010; Jansson 2013).

The studies explored in this volume draw on these and other frameworks but also look beyond how smartphones and tablets are used to consider what impact these devices are having on society and even the environment.

Looked at from an industry perspective, and similar to the introduction of the Walkman, smartphones and tablets have been seen or ‘represented’ as ‘disruptive technologies’ (Christensen 2005). From this perspective, these new technologies offer alternative interfaces for human/machine interaction that cut through previous media and information practices delivering content and communication in new ways. In fact, in their examination of disruptive technologies, McKinsey MIG (Manyika et al. 2013) specifically highlight the significance of smartphones in a technology future encompassing mobile internet, the internet of things and the cloud. Indeed, of the 12 disruptive technologies they identify, four make mention of smartphones – including the issue of battery and electricity supply and consumption to be discussed in this volume. Hence it is important to assess whether this is just another representation of the future of smartphones, whether this is the ‘reading’ agreed to by users or w...