eBook - ePub

Bridging Worlds

Understanding and Facilitating Adolescent Recovery from the Trauma of Abuse

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bridging Worlds

Understanding and Facilitating Adolescent Recovery from the Trauma of Abuse

About this book

With Bridging Worlds, you will learn to uncover the roots of teenage problems – the causes behind symptoms such as self-destructiveness, anger, recklessness, and violence. Originally published in 1998, this title shows you how to develop treatment guidelines and thoughtful frames of reference that address the problems of teenage violence, pregnancy, truancy, and delinquency. It will help you detect when the reckless, even frightening, behaviour of adolescents is a cry for help and show you what you can do to defuse the situation, make authentic and meaningful connections, and offer valuable help.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bridging Worlds by Joycee Kennedy,Carol J. McCarthy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I:

A New Vision

Reclaim

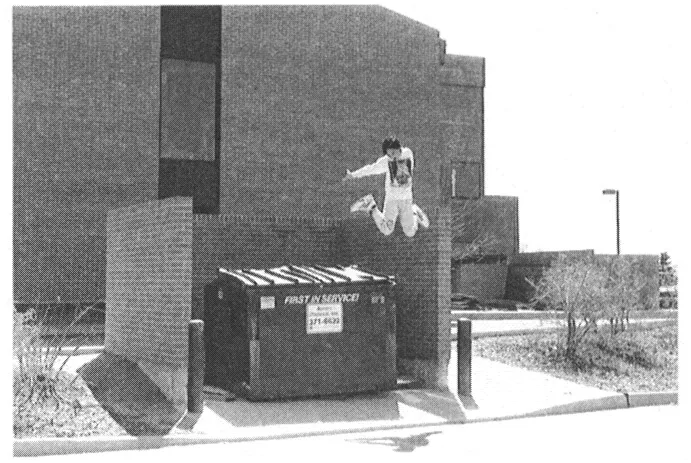

Hurdling over a sawhorse, a youth remounts his skateboard, veers a sharp ninety degrees to his left, ascends a curb, races down the sidewalk, drops off another curb, hits the uneven street … clickety-clack, and pulls up to meet his friends at the entrance to the shopping mall. Deftly dismounting from his board with a weight shift to the rear edge, the youth takes his position beside a friend on the brick wall and lights a cigarette. “F__ the old man!” he fumes, “That’s the last time I’m going home.”

Young people tend to reflect the images of adult role models. Therefore, it is not unlikely that abused and neglected youths may create the above images in our society. Joseph Campbell (1988), the late scholar, author, and teacher wrote, “A hero is someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself” (Campbell, 1988, p. 151). “Contemplating heroic lives, lives distinguished by physical or psychological courage, and sometimes both, helps to fortify one’s own soul and inspire one to be a little better than deep down, one worries one is” (Epstein, 1991, p. 336).

These youths are heroes, albeit often misguided ones. Their heroism results from their creative survival techniques. The hardships they have endured are frequently beyond the scope of understanding of many professionals. An individual’s ability to survive hardships such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse is heroic in itself. “Children in the United States are five times more likely to be murdered and 12 times more likely to die because of a firearm than those in other industrialized countries” (Rocky Mountain News, 1997, February 7, p. 3A). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) studied twenty-six countries between 1990 and 1995; the CDC reported, “Five countries—Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, and Taiwan—reported no intentional firearm-related deaths among children under 15” (Rocky Mountain News, 1997, February 7, p. 3A).

It is the responsibility of all adults to pay attention to the ways in which they have contributed to the harm of children and adolescents. Of equal importance is the need to help youths heal from exposure to such violence.

Society has yet to build an appropriate track channeling the heroism of these youths. Teenagers who have overcome and endured traumatic heritages have developed the power and beauty of the vintage Porsche—with dignity and grace acquired from years of racing.

Current tracks for American teenagers who have experienced severe child abuse include detention centers, departments of special education, hospitals, foster or group homes, and day treatment centers. Unfortunately, parents are sometimes excluded from meetings, and when they are included, they are often blamed for their teenager’s difficulties. Family structure is sometimes scapegoated, but in and of itself, it does not cause child abuse. Diversity in cultural heritage is often scapegoated and misunderstood. Cultural diversity plays an important role in identity development throughout childhood. The reality for many of these youths is that they have unique family structures. Not all of the caretakers of these youths are abusive. A new vision of families is important.

Chapter 1

Families

There was a time when the term “family values” generally referred to bargains at a fast-food restaurant. It has now been taken over by politicians to refer to alleged mainstream mores that have supposedly been on the decline in the United States. A lack of family values has been blamed for such diverse issues as alcohol and drug use, sexuality between anyone except married heterosexuals, and gang violence.

This political rhetoric collapses under scrutiny, however. A significant number of traditional families are responsible for a great deal of violence in this country. Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse of children within the context of nuclear families is far from unusual. Such abuse often occurs uninterrupted throughout generations. No socioeconomic, racial, or ethnic group is immune to the victimization of children by family members. While the verbalized value may be that children are not to be treated as objects, the latent message is often in direct contradiction to such a premise.

Nuclear families have been attributed considerable power. In political campaigns, such families are often cited as a source of strength, as well as an endangered structure due to the increase in alternative family forms. The following are some of the factors often cited as contributors to increasing stress for teenagers: the rising divorce rate, the increase of single-parent households, and the increase of two-working-parent households. There are many experts who view these factors as directly contributing to adolescent trauma. In some ways they may be influential in the problems that affect teenagers in these environments. Certainly the divorce process often leaves a single-parent home devoid of the resources needed to keep a parent and children in a close relationship. The government, courts, and legal system are increasing their vigilance to ensure that the absent parent shares resources responsibly. However, many of these families remain economically poor, but are relationally rich.

The nuclear family does not represent everyone’s experience, nor is it even considered ideal for many people. The term family of creation is used in this work in an effort to include the many creative family configurations to which people belong. The parental composition of the family environment—whether it consists of both biological parents, adoptive parents, stepparents, foster parents, gay or lesbian parents, one parent, or no parents (grandparents often inherit the offspring of their children)—does not have to create traumatic stress. Of importance is not the structure of the family, but the quality of connection within it. Some adults in our society have few positive leadership skills. They may lie and manipulate to get their way, and are often self-centered and self-seeking. These adults will have difficulty providing a rich psychological environment for teenagers. Youths will most likely experience healthy development under the guidance of one or more good adult role models. An adult needs to have his or her own life under control to raise a child well. Such adults must have a developed sense of responsibility, ethical standards, and a strong interest in providing the direction needed to help youths make the transition into the adult world with educated minds and healthy bodies.

Adolescents will painfully attempt to adapt to a variety of living arrangements that represent unhealthy environments. The experiences they suffer during this very vulnerable stage in their lives lay important foundation blocks for adulthood. Too often young people suffer in environments where people are mugged, robbed, or raped regularly. They live with drug and alcohol abuse in their own homes as well as being surrounded by it in the neighborhood. Teenagers suffer from lack of resources needed to make the most of educational opportunities. A self-conscious, hungry adolescent will not take the best advantage of a classroom discussion. In the worst cases, young people suffer parental neglect—even abandonment, and physical, sexual, and verbal abuse. Two unfortunate foundation blocks put in place under these conditions are fear and distrust. These are traits of a soldier at war.

Mass media can also have a deep impact on a child’s development. Children and adolescents are exposed regularly to violent images on television, whether real or fictitious. They may hear adults talking about current events. The degree to which a young person’s development is affected by hearing about deaths in Somalia, riots in Los Angeles, civil war in Rwanda, the passage of antigay legislation in Colorado, and the shooting of a child down the street may vary from individual to individual. Such images, however, do shape young people’s beliefs about themselves and the world around them.

In addition, many adult role models have become the subjects of TV news for committing murders, perpetrating fraud, harassing women, embezzling company funds, sexually assaulting young children, being obsessed with careers while neglecting family members, stockpiling vast sums of money while ignoring charity, and demonstrating sexual promiscuity.

One of the remarkable, yet often frustrating qualities of adolescents is their ability to sense reality amid adult mirages, such as the hypocrisy of the parent who asks his or her teenager not to drink, and comes home himself or herself intoxicated from parties most weekends. In other words, teenagers are not easily fooled. One of the developmental tasks of childhood involves internalizing societal values. Many of these values may not be acknowledged as valid by those in power, but the presence of such values is seen in the daily lives of many. Indeed, teenage violence may be a logical, although terrifying, response to adult hypocrisy. An example is Gina Grant, who murdered her brutally abusive mother. Gina, a popular, bright fourteen year old, was taught appropriate behavioral conduct from birth, but experienced her mother’s opposite enactments. There was a convoluted logic to the brutal act Gina committed.

The Gang Family—An Adolescent Response

Tracy Chapman (1992) provided a vivid portrayal of adolescent violence, and the lack of adult accountability to such violence, in her song, “Bang Bang Bang.” The lyrics explore adults providing weapons to youth, as well as attempting to placate young people without giving them what they truly need. “You go and give the boy a gun/Now there ain’t no place to run to.”

The children of our society are not only killing adults, they are literally killing each other. News accounts are filled with stories about gang involvement, often termed “senseless violence” by the media. While it may be deplorable, frightening, and upsetting, it is anything but senseless. To many of the adolescents involved, a gang is a family of creation.

While degrees of structure vary from one gang to another, most have clear membership criteria, initiation rituals, and rules by which to live. Certain clothing, peer groups, activities, and language are acceptable. Any behavior outside of a range of activity is suspect or dangerous. Values are generally clear as well. For example, a high degree of loyalty between members exists, and membership is meant to last a lifetime.

The parallels between traditional family groups and gangs are interesting to consider. Families generally have clear norms, expectations, and rules. If someone joins the family, through marriage or birth for example, a range of rituals has been established as rites of passage into the family. Families often have similar cultural and ethnic backgrounds, and socioeconomic status. Membership is meant to last a lifetime, but if someone wishes to leave the family, there are rituals designed for that as well. Gangs and families have the potential to fulfill needs of affiliation, protection, and structure. In a chaotic world, people tend to gravitate toward the familiar. The same is true when resources are scarce, or when real or perceived danger is present.

Shanika’s Story

Shanika is a seventeen-year-old African-American young woman who lives in a war zone in the United States. Many of her friends and acquaintances have been injured or killed by other young people. Much of this has been the result of gang violence. Shanika probably turned to gangs for many reasons. Both of her parents are dependent on drugs and/or alcohol. She has been raised primarily by extended family, one of whom has acted as a primary caretaker for Shanika whenever life with her mother became too dangerous. She has not had contact with her father for quite some time. He has been peripherally involved in her life, at best.

Shanika was articulate in discussing her participation in gangs, although she was initially quite guarded about it. In much the same way as a young person might feel protective of her own family, Shanika relayed information about her gang life carefully. Her ambivalence about gang involvement is similar to her ambivalence about her biological family. Both supply some needs at times, but at incredible emotional and physical costs. The ways in which Shanika had to compromise herself in her families of choice and origin have been life threatening at times.

On one occasion, Shanika was accompanied to court by her mother, grandmother, and therapist. Shanika’s mother was clearly inebriated. This was the first time she had come to court to support Shanika in any way. Shanika’s conflicted feelings about her mother were clear at this point, as she attempted to justify her mother’s actions.

The following is a transcription of an interaction between Shanika and her therapist:

| Shanika: | My momma’s sick again. She has to go to the doctor. |

| Therapist: | Your mom doesn’t seem to take very good care of herself. |

| Shanika: | Why do you think I always want to be over there? |

| Therapist: | You take care of her when you’re there? |

| Shanika: | Yeah. No one else does. |

| Therapist: | I see. Well, who takes care of you? |

| Shanika: | No one. I do. |

| Therapist: | Doesn’t give you much of a chance to just be a kid. |

| Shanika: | Nope. |

Examples of adult misunderstanding occurred when Shanika was briefly hospitalized for self-destructive behavior. While she was angry at her therapist at first, the goal of the hospitalization was clearly spelled out for her—Shanika needed to be safe. The therapist hoped for a short hospitalization to stabilize Shanika. A fairly quick return to home and day treatment was sought.

The hospital decided upon different goals for Shanika after working with her for two days. Because she had at one point been involved in gangs, they felt that she needed long-term inpatient psychiatric treatment in order to break her connections with other gang-involved youth. They were willing to certify her to accomplish this goal, which was more possible prior to the impact of managed care. The day-treatment therapist strongly disagreed with this recommendation and was willing to fight for Shanika’s return to home and day treatment. It seemed extremely unrealistic and inappropriate to attempt to break Shanika’s ties to her family, community, and friends. Her family of creation felt threatened by the staff of the psychiatric hospital. Even though her connections may not have been ideal, attempting to disconnect her seemed cruel and pointless. Helping Shanika survive and grow in the context of her world was the goal of her day treatment.

In addition to the psychiatric staff difficulties, Shanika had a court date for a municipal charge two days after she was hospitalized. When her grandmother called to inform the court that Shanika could not attend due to her hospitalization, she was told by a clerk that a warrant would be issued for her arrest for nonappearance. The clerk would not allow Shanika’s grandmother to speak with anyone else about this matter. Her grandmother called the day treatment therapist for assistance with the legal system.

Shanika was not in shape to leave the hospital for any reason at that point. When the therapist called to advocate on Shanika’s behalf, she spoke to the person who had previously denied any assistance to the grandmother. After identifying herself as Shanika’s therapist to the clerk, it was confirmed that she had told the grandmother that a warrant would be issued if Shanika did not show up. She then very politely connected the therapist to the deputy district attorney in charge of the case. Upon speaking to him and explaining the situation, the attorney not only agreed that Shanika should n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I: A NEW VISION

- PART II: STRUCTURAL CHANGE

- PART III: HEALING A GENERATION

- Appendix A. CASTT Intake Information

- Appendix B. A Troubled Voice

- Appendix C. Advocacy

- Appendix D. Goals for Child Recovery from Traumatic Stress: A CASTT Model

- Appendix E. CASTT Information Sheet

- Bibliography

- Suggested Readings

- Index