![]()

1 Cyprus

From an economic miracle to a systemic collapse and its aftermath

Andreas Theophanous

1 Introduction

The objective of this chapter is to provide an analytical description and assessment of how Cyprus reached a systemic collapse in March 2013 following more than three decades of a remarkable socio-economic record. The chapter examines the characteristics and the dynamic changes of the economy since the 1970s including the current crisis.1

The Republic of Cyprus is a small island state located in the eastern Mediterranean. The population in the government-controlled areas of the Republic of Cyprus was about 858,000 in 2013. In the occupied northern part of Cyprus it was estimated that the population was about 280,000; more than 50% are settlers from Turkey. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean after Sardinia and Sicily with an area of 9,251km2. Since 1974 the Republic of Cyprus has controlled only 59.5% of the island’s territory; 35.2% is under the control of the Turkish troops of occupation, while 2.6% is a buffer zone. The two British bases established in 1960, located in the southern part of the island, constitute 2.7% of the territory of Cyprus. The island has a rich history, going back to antiquity, as evidenced by its archaeological heritage. Cyprus obtained its independence from Britain in 1960 and joined the European Union in 2004 and the eurozone in 2008.

As a small island state, Cyprus shares similar characteristics with many other small states, in that the country is highly dependent on international trade and on a narrow range of exports, including tourism. It is therefore highly exposed to economic forces outside its control. The high exposure to external economic conditions was a main reason why the island underwent serious economic crises in 2013, although, as explained in this chapter, internal factors exacerbated the negative effect of economic vulnerability.

The discussion contained in the chapter takes place within a particular political context. While this applies to all countries, in the case of Cyprus the political aspects are especially important, particularly because in 1974 Cyprus experienced the Turkish invasion which led to the loss of territory and ethnic cleansing. The serious socioeconomic and political repercussions of this event are felt to this day.

This chapter is organized as follows. In Section 2 the major characteristics of what was described as an ‘economic miracle’ and its broader implications are outlined. We also explain why this description is appropriate. Section 3 outlines the reasoning for advancing a customs union with the European Community and subsequently accession to the EU and adoption of the euro. We also describe the country’s socioeconomic record and the structural weaknesses of the economy which at the time were underestimated. Section 4 examines how Cyprus found itself on a fatal path leading to what may be described as a systemic collapse. We assess the record of the banking sector and how it became problematic leading the economy to an unprecedented crisis. Section 5 describes and assesses the Eurogroup’s decisions in March 2013, relating to Cyprus’ financial crisis and the fallout since then. In the last section we put forward some concluding remarks as well as policy recommendations and suggestions for further research.

2 Understanding the economic miracle

2.1 The Turkish invasion of 1974

When Cyprus acquired its independence in 1960 it was a poor, undeveloped and essentially an agrarian country. With a philosophy of a mixed economy and a high work ethic, Cyprus managed to achieve high growth from 1960 to 1973, on average about 7% annually in real terms. This remarkable record was abruptly interrupted by the Turkish invasion of 20 July 1974. Military operations continued until 16 August 1974 when there was a final cease-fire. In addition to the immense loss of human life, wounded and missing persons, Cyprus lost about 38% of its territory and also suffered ethnic cleansing. Almost 200,000 Greek Cypriots who lived in the northern part of Cyprus were displaced. Turkish Cypriots who lived in the southern part of the island were gradually moved to the area under the control of the Turkish occupation troops.

Cyprus lost its international airport in Nicosia, its major port in Famagusta, most of its tourist infrastructure (Famagusta and Kyrenia) and 70% of its productive resources. The economy was severely dislocated and dismantled as the occupied territories included most of the citrus growing areas, the best agricultural land and the most developed tourist areas (Whitaker, 1980; Bamber, 1982; Theophanous, 1991). Many Greek Cypriots were so shocked by the events that they sought refuge and opportunities for a new beginning in foreign lands.

Consequently, ever since, economic activity has been taking place in the light of these events and the political fallout associated with them. Yet the country survived, the economy was successfully revived, the pace of emigration was gradually reduced and, eventually, after 1980, reversed. It is under these circumstances that the change of perceptions and psychology took place as well as the consolidation of law and order, the attraction of foreign investment, the recovery of the economy and indeed the survival and continuity of the Republic of Cyprus.

2.2 The economic recovery

The Cypriot economic recovery and the subsequent process of growth, modernization and development were so successful that they were described as an ‘economic miracle’ (Economist, 1977; Christodoulou, 1992). Although exogenous factors played a role in the immediate recovery and subsequent modernization and further development of the area under the control of the Republic of Cyprus, it was the endogenous dynamism of the Cypriot economy and society which mostly led to the ‘economic miracle’ (Christodoulou, 1992; Theophanous, 1995). Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dropped sharply by 32.7% during the period 1973–1975 and unemployment rose to almost 30% during the same period, but the government managed to reverse the situation. By 1979, the GDP of Cyprus recovered in real terms, and was 61.8% higher than in 1975. Furthermore, unemployment was reduced to about 2%. By the beginning of the 1980s, Cyprus, for the first time, began to experience a net-inflow of people who had emigrated in 1974 or even before.

The economic structure of the country went through a major transformation. Cyprus recovered and embarked on a path of a remarkable growth and development. What has been achieved was comparable with the achievements of West Germany after the Second World War.

Greek Cypriots had understood, after the military defeat and the occupation of a substantial portion of Cyprus territory by Turkey that if they did not succeed in the domain of the economy the future of Cyprus would be bleak. Economic recovery and subsequent development would keep the population and also guarantee the continuity of the Republic of Cyprus. It was also considered that the economy would constitute a major pillar in the peaceful struggle for the solution of the Cyprus problem in an integrationalist manner.

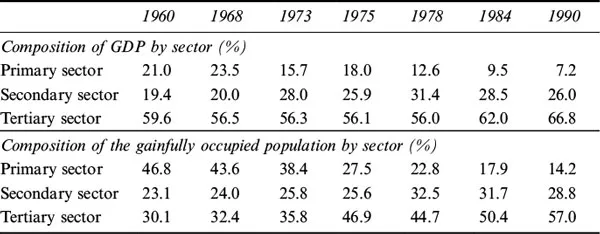

During this process there was a radical socioeconomic transformation, as can be seen from Tables 1.1 and 1.2.

Table 1.1 shows that during the period under consideration the primary sector (mostly agriculture and fishing) declined from about a fifth of GDP in the 1960s to just about 7% in 1990. On the other hand, the secondary sector (mostly manufacturing) and the tertiary sector (mostly tourism and market services) increased their share of GDP. These structural changes were also reflected in the composition of gainful employment.

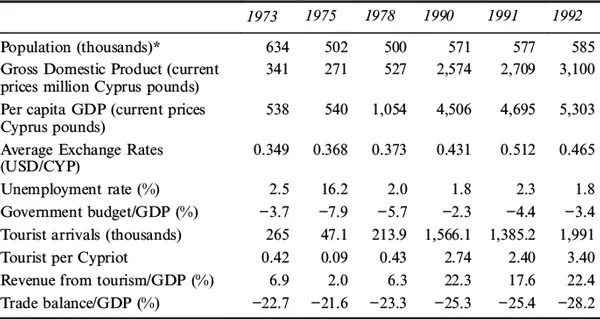

Table 1.2 shows that during the period under consideration, GDP per capita increased rapidly, whereas unemployment decreased considerably. There was a remarkable growth in tourist arrivals and in the revenue from tourism.

The bulk of growth in the period from 1980 to the early 1990s originated in services, particularly those associated with tourism, rather than secondary activities. The share of the services sectors in gross value added rose from 55% in 1980 to 67% in 1990. Tourist related sectors such as restaurants and hotels and transport storage and communication also saw their distribution shares rise significantly. Tourist receipts rose more than tenfold, from €123 million in 1980 or 9.5% of GDP, to €1.3 billion or 22% of GDP in 1990. The tourist related sector of hotels and restaurants was growing at an average pace of 13.9% annually in value added terms in the 1980s and provided the foreign exchange needed to fund imports and finance considerable infrastructural works.

Table 1.1 Economic structure (1960–1990)

Source: Cyprus 1960–1990, Time Series Data, Department of Statistics and Research, Ministry of Finance, Republic of Cyprus.

Table 1.2 Key economic and social indicators (1973–1992)

Source: Economic and Social Indicators 1992, Planning Bureau, Annual Report 1993, Central Bank of Cyprus.

* The population in 1973 included 18.4% Turkish Cypriots. Thereafter the population refers only to the government-controlled areas of the Republic of Cyprus.

Manufacturing activity also contributed considerably to growth in the 1980s driven by export demand for low value added goods mainly from Arab countries. However, manufacturing activity which was based on cheap labour and low value added goods peaked in the middle of the decade and declined thereafter. Lack of change in the techniques of production and innovation rendered the Cypriot manufacturing sector virtually unable to compete in the EU and internationally.

This successful outcome was brought about by various factors, including that:

1 The government achieved social cohesion and also inspired the people. On the one hand, it encouraged entrepreneurship and, on the other, persuaded the unions to agree to a 25% reduction of salaries for three years. Furthermore, the government continued and enhanced its indicative planning through five year plans.

2 The government also encouraged tourism in Paphos, Limassol, Larnaca, Agia Napa and Protaras; prior to 1974 there was little or no tourist activity in those areas. Tourism soon developed to be a major sector and pillar of the economy.

3 There was a massive expansion of the public and broader public sector; new jobs were created as well as new institutions.

4 The government adopted a policy of sustained fiscal and monetary expansion to stimulate the economy. It also provided specific incentives to encourage economic activity. This included an especially low tax rate of 4.5% to encourage offshore business activity.

5 The vast expansion of the construction industry and related business sectors were particularly important for the recovery. The government financed and/or subsidized the building of housing at various levels for the refugees. Likewise, there was heavy building of infrastructure including hotels and other tourist facilities.

6 Cyprus also encouraged light industries. From 1974 to 1984 there was a modest expansion of exports of agricultural and light industrial goods especially to the Arab World.

7 There was also a modest amount of foreign aid especially after the invasion. Nevertheless, this was not the decisive factor for survival and recovery.

The economic miracle had some shortcomings: a sizable portion of jobs initially created were of low added value, while the expansion of tourism was anarchic and on several occasions without respect for the environment. Be that as it may, it is essential to understand what the miracle was all about: the fast economic recovery and above all the survival and continuity of the Republic of Cyprus. During this process there was a radical socioeconomic transformation (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

During this period there was a fast process of urbanization which was related to the post-war realities: most Greek Cypriots who left their villages in the northern part of Cyprus eventually were relocated in the towns. Furthermore, gradually the primary sector decreased and the tertiary sector grew. With the remarkable growth rates there were major changes in the social norms and broader attitudes. The massive expansion of tourism had its impact as well.

With the economic recovery advancing, cases of nepotism were observed as well as the deepening of patron-client relations at various levels. Furthermore, with the growing affluence, the strength of the trade unions especially in the civil service, the broader public sector and the banking sector became a major characteristic of the economic structure; these excesses would constitute major contributing factors for the crisis which culminated in 2013.

3 Accession to the EU and the adoption of the euro

3.1 The political context

The Republic of Cyprus was first linked with the Common Market in 1973 by means of an Association Agreement. The progress of the relationship was impeded – but not thwarted – by the Turkish invasion and occupation of 38% of the territory of Cyprus in 1974. With the economic recovery, further growth and subsequent modernization of Cyprus and with the appropriate political will, the country was successful in completing a Customs Union Agreement with the European Community in 1987 which became effective on 1 January 1988. In addition to its economic aspects, this agreement had important political implications; its provisions referred to the Republic of Cyprus as a whole and not only to the area under the control of the government. Furthermore, on 4 July 1990, Cyprus submitted an application for membership, joined the EU in May 2004 and adopted the euro in January 2008.

When Cyprus applied for membership of the EU on 4 July 1990 it was expected that the accession process and accession itself would contribute to a fair settlement of the Cyprus problem. Furthermore, at a time of major changes in the European and international environment, most Cypriots believed that it was time for such an option (Theophanous, 2004).

Within this new political framework, two vital objectives of the Republic of Cyprus were (a) accession to the EU and the solution of the Cyprus problem in an integrationalist manner; and (b) the further modernization of the economy and the harmonization with the EU standards and norms.

Cypriot policymakers did not realize that despite the overall successful economic record and metamorphosis of the society, major socioeconomic problems existed and that if these were not adequately addressed, what was achieved could be undermined (Christodoulou, 1995). It was a time of enthusiasm and high expectations.

Accession negotiations started in 1998. During the accession negotiations an international effort supported by the UN, the EU, the USA and NATO was taking place for the solution of the Cyprus problem. Cypriot policymakers ...