eBook - ePub

Biomarkers

Biochemical, Physiological, and Histological Markers of Anthropogenic Stress

- 365 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biomarkers

Biochemical, Physiological, and Histological Markers of Anthropogenic Stress

About this book

This book provides a survey of biochemical, physiological and histological biomarkers of environmental stress, along with evaluations of the strengths and weaknesses of various techniques for different applications. It features in-depth coverage of such topics as DNA adducts, acetylcholinesterase, ATP, endocrine mechanisms, blood chemistry, histopathological biomarkers, stress proteins, foreign and endogenous metabolites, metallothioneins, to name only a few.The book will be especially useful to toxicologists, biochemists, histologists, immunologists, risk analysis specialists, environmental managers, regulators, environmental scientists and engineers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biomarkers by Robert J Huggett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Physiological And Nonspecific Biomarkers

Foster L. Mayer, Donald J. Versteeg, Michael J. McKee, Leroy C. Folmar, Robert L. Graney, Delbert C. McCume and Barnett A. Rattner

Physiological and nonspecific biomarkers have been used extensively in the laboratory to document and quantify both exposure to, and effects of, environmental pollutants. As monitors for exposure, biomarkers have the advantage of quantifying only biologically available pollutants. As measures of effects in the laboratory, biomarkers can integrate the effects of multiple stressors and can assist in elucidating mechanisms of effects (i.e., mode of action). These laboratory studies will be critical to validate biomarkers as methods to instantaneously assess the condition of a population, community, or ecosystem.

Despite their utility in the laboratory, biomarkers have not been extensively applied in actual environmental assessments of effluents, nonpoint source pollution, and effects of land use practices. The lack of extensive use of biomarkers has many causes, including:

- the relative ease and simplicity of analytical chemistry methods for many environmental contaminants

- the disproportionate emphasis on development of biomarkers rather than their application

- the present difficulty in causally linking biomarker effects with specific environmental alterations

- the present lack of a direct linkage between biomarker effects and relevant population, community, and ecosystem-level effects

This chapter discusses the utility of physiological biomarkers and lists the criteria to be used in selecting biomarkers to address specific ecological questions. After a general discussion of this topic, several specific biomarkers of exposure and effects are described individually. For each of these biomarkers, research needs are identified for further development and for evaluation of their ecological relevance.

Introduction

During the past 20 years, toxicological effects in the aquatic environment have been assessed from the suborganismal to the ecosystem level of organization (Larsson et al. 1985; Miller 1981). Research, primarily at the population, community, and ecosystem levels, is being used to monitor environmental effects, conduct hazard assessments, and make regulatory decisions. The predictive utility of research at these levels of biological organization is limited because ecologically important effects (e.g., death or impaired organismal function) have already occurred by the time they can be detected.

Recently, as the discipline of environmental toxicology has matured and environmental regulation has become more complex, biomarkers at the suborganismal levels of organization (biochemical, physiological, and histological) have been considered to be viable measures of responses to stressors (Wedemeyer and McLeay 1981; Goldstein 1981). Biomarkers can allow for rapid assessment of organism health. As tools to monitor biological function and health, they are quantifiable biochemical, physiological, or histological measures that relate in a dose- or time-dependent manner the degree of dysfunction that the contaminant has produced.

Biomarkers can be indicators of either exposure or effects. The best current use of biomarkers is in understanding exposure of organisms to biologically available environmental pollutants. However, the greatest future utility of biomarkers may be in the in situ quantification of effects and diagnosis of cause.

Research from the cellular to the organismal level has not been utilized extensively in situ to address environmental questions. This is unfortunate since information unavailable by otheT methods can be obtained by these means in a timely and cost-effective manner. Current methods need additional research attention, especially in the area of field validation, before they can be used extensively in hazard assessment and regulatory toxicology. For new biomarkers, a sound research strategy for the development and implementation of biomarkers must be prepared and shared in order to direct and focus future research efforts.

The remainder of this chapter concentrates on methods for assessing the health of an organism or population. We review the response of organisms to stressors, discuss the rationale for using biomarkers, review problems associated with the field use of biomarkers for effects, and discuss experimental considerations in the design of field exposures.

Background

Frequently, the focus of biomarker research is to quantify the condition or health of organisms in situ. Health of an organism can be defined as the residual capacity to withstand stress; the more stressed, the less capable is the organism of withstanding further stress (Bayne et al. 1985). Stress has been variously defined, and several excellent discussions are available on it relative to ecotoxicology (Lugo 1981; Pickering 1981). Various uses of stress have become so entrenched that a consensus definition is unlikely (Pickering 1981). Therefore, as discussed by Pickering (1981), it is essential that terminology be specifically defined to avoid confusion among the various terms. In this discussion, we conform to the following concept of stress. Brett (1958) defined stress at the individual level of ecological organization as “a state produced by an environmental or other factor which extends the adaptive responses of an animal beyond the normal range, or which disturbs the normal functioning to such an extent that the chances of survival are significantly reduced.” This definition is essentially consistent with the stressor/stress concept described by Selye (1956) and Fitch and Johnson (1977). A stressor is any condition or situation that causes a system to mobilize its resources and increase its energy expenditure (Lugo 1981). Stress is the response of the system to the stressor via increase in energy expenditure (Lugo 1981).

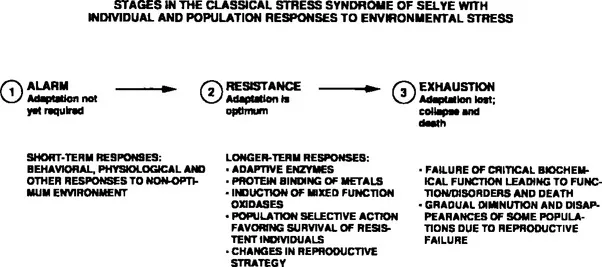

Seyle (1950a, b; 1976) envisaged stressors to produce specific reactions in an organism, which when sufficient in intensity, would stimulate a systemic stress response resulting in the general adaptation syndrome or GAS (1977) further extended the GAS concept to population level responses (1981) provided an excellent critique of Selye’s concept as it relates to quantification of stress in organisms and ecosystems. A modem deviation from Selye’s original treatise is that the general adaptation syndrome (GAS) is itself a specific response based on neuroendocrine stimulation associated with awareness (Mason 1975a, b). Therefore, caution should be exercised in extending Selye’s original concept to assume that biomarkers of GAS are always reliable indicators of chronic stress. For example, Schreck and Lorz (1978) reported reductions in survival of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) without stimulation of GAS as evidenced by plasma Cortisol levels. The reader is referred to Pickering (1981) for a more detailed critique.

Chronic toxicant effects may occur without stimulation of the GAS. Lugo (1981) discussed the importance of energy costs of stress and emphasized the significance of energy drains during exposure to chronic stressors. It is conceivable that reductions in survival, growth, and reproduction might occur via an energetic route without stimulation of GAS. This emphasizes the importance of selecting biomarkers that are intimately related with survival, growth, and reproduction as potential monitors for in situ population effects.

Figure 1. The general adaptation syndrome of Selye (1976).

For additional publications related to stress, the reader is referred to Cairns et al. 1984, Casillas and Smith 1977, Donaldson 1981, Harvey et al. 1984, Johansson-Sjobeck et al. 1978, Lowe-Jinde and Niimi 1984, Mazeaud et al. 1977, Munck et al. 1984, Nolan and Duke 1983, Sibly and Calow 1986, Siegel 1980, Turner and Bagnara 1976, Versteeg and Giesy 1986, and Wedemeyer et al. 1984.

Biomarker Selection and Development

Biomarkers of chemical and physical stressor effects are attractive alternatives to more traditional measures for several reasons. Under field conditions, organisms are exposed to a multiplicity of chemical and physical stressors, against a background of naturally occurring seasonal fluctuations that, in and of themselves, are potentially stressful to the organism. Biomarkers have the potential to act as integrative measures at the suborganismal level to indicate adverse conditions, whether natural or not, preceding population-level effects. In addition, since the toxicological response to a chemical is caused by the interaction between the toxicant and biochemical receptor, biochemical responses would be expected to be the most immediate. That is, these responses would occur before responses are observed at higher levels of organization. Therefore, biomarkers should respond more rapidly than the whole organism.

Biomarkers can be categorized into nonspecific and specific as discussed previously. Biomarkers indicative of a nonspecific response to stress include any measure that is altered by exposure to a variety of stressors. Some of these nonspecific biomarkers (e.g., RNA/DNA, radiolabeled amino acid or nucleotide incorporation, and adenylate energy charge) give direct information about the growth rate or potential of an organism. Nonspecific biomarkers can integrate the simultaneous impacts of multiple toxicants or environmental factors on the organism, since all types of stressors can affect these endpoints. While these measures cannot be used to identify the specific toxicant causing an effect, many environmental situations consist of multiple stressors causing effects in an interactive manner.

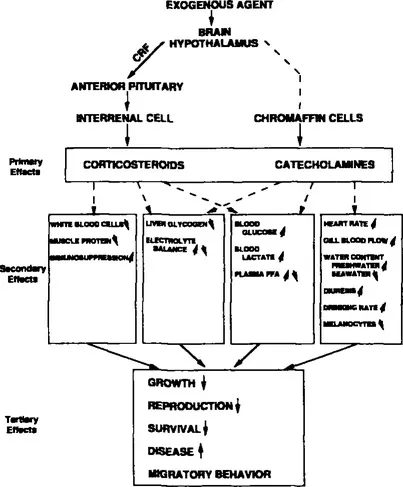

Figure 2. The physiological, biochemical, and population level responses of an organism to stress, corticotropic releasing hormone (CRF), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and free fatty acid (FFA). Modified from Mazeaud et al. 1977.

Specific indicators of stress are of two types: organ- and toxicant-specific. Organ-specific biomarkers include organ function tests, histopathology, organ-specific enzymes, and isoenzymes. Organ function tests include p-aminohippurate uptake by the kidney (Miller 1981) and bromosulfothalein and indocyanine green clearance by the liver (Patton 1978; Gingerich and Weber 1979). To date, these tests have not been used extensively in environmental toxicology; however, they are potentially useful for understanding toxicant-induced alterations in organ function.

Organ-specific biomarkers often depend on detection of certain enzymes at increased concentrations in a few organs. These enzymes appear in blood when those organs are damaged and are indicative of the presence and extent of damage. Lactate dehydrogenase, transaminases, creatinine phosphokinase, lysosomal enzymes, and alkaline phosphatase are examples of enzymes used as organ-specific indicators of toxic effects. Organ-specific isozymes such as lactate dehydrogenase and creatinine phosphokinase, may provide additional information on the specific organ affected in fish. Relatively few studies have used these methods to identify specific organ damage (Lockhart et al. 1975; Versteeg 1985).

Toxicant-specific biomarkers can involve quantification of certain enzyme activities or biomolecules in a tissue. They indicate exposure and possibly effects due to a single chemical or a related group of compounds. Examples include inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity in brain tissue by organophosphorus pesticides (Coppage et al. 1975; Grue et al. 1983; Lowe-Jinde and Niimi 1984), cytochrome P450-monooxygenase (Gooch and Matsumura 1983; Rattner et al. 1989), metallothionein and metal binding proteins (Nolan and Duke 1983; Dixon and Sprague 1981), and amino-levulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) (Berglind and Sjobeck 1985; Finley et al. 1976; Hodson et al. 1984). Toxicant-specific indicators have been correlated with exposure of aquatic organisms to environmental pollutants in the laboratory and the field. To date, however, alterations in these biomarkers have shown poor correlation with population, community, or ecosystem effects.

Methods

Methods for biomarkers in environmental organisms have been largely derived from mammalian medicine. Few methods have been optimized for use with feral organisms, which has made comparison of results generated with different methods difficult. Further, use of the mammalian interpretation of a test result may lead to inaccurate assessments of organism health (Mehrle and Mayer 1985). The use of biomarkers for environmental exposure and effects presents several unique problems, namely variability and selection of the test organism.

Results obtained with field samples are usually more variable than those from the laboratory (Lockhart and Metner 1984). This variability has many causes including increased gene...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Physiologaical and Nonspecific Biomarkers

- 2. Metabolic Products as Biomarkers

- 3. DNA Alterations

- 4. Histopathologic Biomarkers

- 5. Immunological Biomarkers to Assess Environmental Stress

- 6. Enzyme and Protein Synthesis as Indicators of Contaminant Exposure and Effect

- Index