- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This detailed analysis, originally published in 1989 studies the relationship between nation, state and territory. It explores the evolution of nations and the development of the state idea. Consideration is given to the frontier, s the interface between states, the influence of defence requirements, and the dilemmas involved in organizing the internal territorial-administrative arrangements of state territory. Finally the book reviews the geographical problems of empires, in growth and decline, and the impact of international organizations among states. Throughout the book, the themese are given an historical dimension and are supported by numerous maps and examples.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nation, State and Territory by Roy E H Mellor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The nation

The pattern of the political map is moulded by people, individuals acting collectively through a hierarchy of community to shape and direct the political process and government. In democratic regimes people have an opportunity to voice their opinions on how political matters should be managed, but in autocratic or totalitarian regimes it is only those who enjoy the inherited privilege of belonging to the ruling elite (or who have otherwise worked their way into it) who can exercise influence in these matters. For the political geographer the most significant level in the hierarchy of community is the nation — the highest level of identity. The modern concept of the nation crystallized in philosophical debates in the eighteenth century and grew powerfully in expression and coherence in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though social scientists have distinguished between ‘ethnic’ (or ‘cultural’) nations and ‘political’ nations, a quite useful distinction, it is perhaps better in political geography to limit the term ‘nation’ only to groups that have achieved political recognition and have created their own sovereign state. Other groups that have not achieved that status may best be termed ethnic groups or ‘ethnies’, even though many aspire to nationhood in the political sense.

In modern times the nation-state, representing the sovereign-state apparatus and legal nationality of the dominant ethnic group in its territory, has superseded other forms of sovereign state such as that organized around a dynasty. It is important to recognize that every individual has both an ethnic nationality and a legal nationality, which usually but not necessarily coincide. Peoples aspiring to political recognition as nations are in a sense ‘sub-nations’, a term not infrequently met, and often enjoy some measure of autonomy within another people’s nation-state, although sadly some receive little separate recognition or may even be repressed and persecuted.

When aspiring to nationhood, ethnic groups with a well-defined settlement area are in a stronger position than those scattered in penny packets across another’s homeland. The coherent settlement area of the Basques in northern Spain is an important weapon in their struggle for autonomy, whereas the Jews, after their diaspora in Roman times, faced the dilemma of being scattered in small groups mostly in towns across the Empire. The pressure for political identity and autonomy by aspirant nations has underlain much instability in the political map. It was a major factor in the disintegration of the dynastic Habsburg Empire and the recasting of the map of East Central Europe after 1919. But instability may also be generated when a nation becomes expansionist, seeking new settlement areas or the domination of other peoples, as demonstrated by the Japanese in East Asia earlier this century.

Though common bonds may long have laid dormant, formation of a national identity requires that innate sentiments are encouraged and codified to coalesce into nationhood. The leadership may come from an elite or aristocracy or even from the broad ranks of society, but certainly the intelligentsia will play a key part in codifying the national language, generating a national literature, gathering music and recording folklore, legend, and history. It is usually possible to identify a focal area or core where the national movement is stimulated and from which national aspirations are disseminated to recruit new members. Later, this core area often acts to create centripetal forces to draw the nation together, for within the perceived national territory, there are sometimes groups of suspect loyalty whose influence generates destabilizing centrifugal tendencies, so that the core must act to counter them.

DEFINING THE NATION

A nation may be described simply as comprising people sharing the same historical experience, a high level of cultural and linguistic unity, and living in a territory they perceive as their homeland by right. There is a further but less readily definable dimension in the mental perception of the members of the group of their common heritage and ‘togetherness’. This spiritual or metaphysical dimension was well summed up in Kipling’s poem ‘The Stranger’. In nationhood, people with common traits and aspirations achieve recognition of their communal identity and their right to do things their own way, usually termed their ‘way of life’. The emergence of national identity has usually been a lengthy process around which has been built an elaborate symbolism, using events, personalities, and even places from historical experience, often given an almost mythical quality as the national ‘iconography’. The interpretation of this iconography is passed from generation to generation through the educational system which inculcates the mores — the values and customs — of the nation into its members, seeking to stimulate patriotism and national pride. Because man has a strong feeling of territoriality in his make-up, the territorial dimension is a powerful element in national iconography, reflected in such mental images as Blighty for the British, die Heimat for Germans, or the Russians’ Matka Rossiya.

Through the strength of attachment to what it believes to be its ‘national territory’, the nation often comes into conflict with neighbours, who may also covet part of it. The geographical analysis of territorial disputes forms an important part of political geography, but the geographical interest is even wider, since the nation’s ‘way of life’, its social and economic expression, makes a deep impress on the landscape. This latter impress does, of course, inherit much from the political ideology under which the nation lives and, while this is often a free choice of the majority of the members, it may be imposed from outside or by a powerful ruling elite that gains much of its strength from external support.

The political expression of the nation’s aspirations we may term ‘nationalism’. Nationalism uses the elements and symbolism of national identity to express the objectives of the nation’s political grand strategy. It builds on the nation’s hope and fears, arousing popular support by appeals to national pride and to patriotism, not uncommonly couched in a promise of a new golden age, often resurrecting a popular view of some historical or even near mythical episode in the nation’s development. To attain and sustain national identity and win recognition of nationhood, a political strategy is inescapable, and consequently every nation has its nationalism. When that nationalism contains aggressive or expansionist, even racist traits, its jingoism can pose a scenario for conflict, often emotively presented as a ‘struggle for national liberation’.

Seton Watson (1977) noted that a ‘scientific’ definition of nation had never been achieved and probably never will be. Each nation is unique in the way its elements are combined, let alone how successfully they have jelled into a durable identity. The most significant elements in nation-building are language, religion, and historical experience, but there are also more unquantifiable ones such as custom and usage or the sense of togetherness. It is usually difficult enough to define what holds one’s own nation together, let alone any other. If we take elements like language and religion, even custom and usage, it is difficult for an outsider to understand why, say, Bavarians and Austrians do not feel themselves close enough to merge into a common identity — is it historical experience or some other element that separates them? Historical experience might certainly account for their separate identities, but there also seem to be far less tangible qualities that motivate their distinctiveness. It is equally difficult to appreciate why in some instances (the Swiss, for example) strength of common historical experience and a common consensus of aspirations have been sufficient to weld into nationhood groups without a common linguistic or cultural background. No particular combination of elements seems to make inevitable the generation of a national feeling among a group, nor is such sentiment precluded simply because a particular trait is absent.

LANGUAGE

We all learn a ‘mother tongue’ as children and some of us later become fluent in other languages. Language is central to any group as a means of communicating ideas and instructions, though each language by its nature has an important influence on how ideas, concepts, values, and imagery are expressed. Language, culture, and perception are intimately intertwined. It is thus not surprising that language has been a key element contributing to a sense of national identity. Superficially, at least, it is one of the easiest indicators to quantify ethnic groups: census-takers have commonly defined ‘ethnic affinity’ on the basis of ‘mother tongue’ or other attribute of language.

In Europe, language as an identifier of national groups came with the shift to the vernacular in law and administration from the fourteenth century. The development of a standard written form received a considerable stimulus with the introduction of printing. A further stimulus came in the eighteenth century as interest awoke in folklore, dialects, and oral traditions, which generated additional codification and classification of languages. Compulsory education and rising literacy spreading the readership of newspapers and books during the nineteenth century, as well as the influence of military conscription, added still more encouragement to the use of standard national languages.

The evolution of a standard national language often provides clues to the geographical pattern of national emergence, indicating the core area from which a national movement disseminated. Standard written and spoken English is marked by the rise of the East Midlands as a focus of population and economic strength from the fourteenth century, especially with the increasing concentration of political power. It coincided with the use of English instead of Latin by the judiciary and the influence of London was enhanced as it grew as the centre of printing and publishing in the fifteenth century. The late and incomplete submergence of Scotland under the English Crown is still reflected in differences of usage and vocabulary, for standard English did not usurp the older Scots tongue until the seventeenth century.

The process was slower and less complete within the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, where Latin remained the medium of law and administration, but the various princely chancelleries increasingly used the local German speech in deeds and documents, and by the late fifteenth century, the Emperor Maximilian had managed to establish a reasonably standardized usage. The Imperial Chancellery in Prague had given the initial leadership, but with the decline of the Luxemburg dynasty, however, further development passed to the Wettin Chancellery in Saxony. This usage was strengthened when Luther used it for his translation of the Bible and it became the preferred style of book publishers. By the mid-eighteenth century, long before national unity was achieved, the German states had a standard written literary language and this ‘paper’ language became the spoken medium, a development hastened by political unity after 1871. Local dialects are still widely used, but in the larger towns the spoken language lies between dialect and the norm taught in schools. Regional associations carefully nurture dialect, reflecting the strong regional element in German life. Differences remaining between north and south are perhaps reflections of the lack of an early focal point in the growth of national identity, while the distinctiveness between Berlin and Vienna in speech and usage accentuated the feeling of separateness between the Hohenzollern and Habsburg empires.

The Low Countries saw their Platt German dialects, in the beginning closely related to Low Saxon and Rhine Frankish, emerge as a distinct literary language. The common origin as a West Germanic tongue is inherent in the name Dutch (the same as Deutsch (German)) though Nederlandsch came into use in the seventeenth century, becoming the official name in 1815. The modern standard language is based on the Holland dialect of Amsterdam, where political and economic power lay in the formative seventeenth century. The separation of Dutch from German arose from the active literary life in the local dialects from the middle ages onwards. The concentration of mercantile towns, compared with the more sparsely settled areas of Low German speech in the broader geographical framework, created a healthy milieu for the preservation of local usage, while the upper and merchant classes, strongly influenced by cultural streams from the south, found little affinity with the ‘High’ German tradition. Furthermore, the struggle against Spanish domination made language a significant element in national identity before it came to fill that role in other German lands. Acceptance of Calvinism tended to weaken links with the Catholic Rhineland and Lutheran North Germany. Some divergences remain between the resolutely Catholic Brabant and Flemish lands and the remaining provinces.

Although language has not been a prime factor in the emergence of national identity in Switzerland, one might have expected the German cantons in their long struggle with the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg to have developed a linguistic identity on the model of the Netherlands. Though the distinctive Alemannic spoken dialects are far removed from the written idiom of Saxon German used by Luther, it has been suggested that acceptance of this latter form as the official language, so patently different from everyday speech, arose because Zwingli chose to use it to dispute articles of faith with the Lutherans in their own written form. It has also been suggested that the local dialects were too jealously regarded to allow evolution of a synthetic written and spoken Alemannic standard form.

Language played a key role in the early emergence of a close-knit national identity in France. Once again, the ascendancy of one region, the Ile de France, has left its impress, with the early romantic literature in the Midi, using Provençal, eclipsed by the written and spoken dialect of the politically vigorous north. The early sixteenth century marked a drive for unification as fears of outside pressures grew, reflected in the royal decree of 1539 that only the northern form of French should be used in provincial chancelleries. By the seventeenth century the written language of the Parisian bourgeoisie had come to be accepted as the norm, though its use in speech took longer to establish. The local dialects, the patois, were usurped by a standard spoken language as the centralizing tendencies initiated by the Revolution spread, reinforced later by compulsory military service and universal schooling. The distinctive regional speech of the early Romance period has been almost obliterated, though provincial ways remain of pronouncing the standard language, but the nature and content of that language and its usage have been jealously guarded since 1635 through the Académie française. A significant element in the iconography of French national identity is a belief in the superiority of their language (‘what is not clear is not French’).

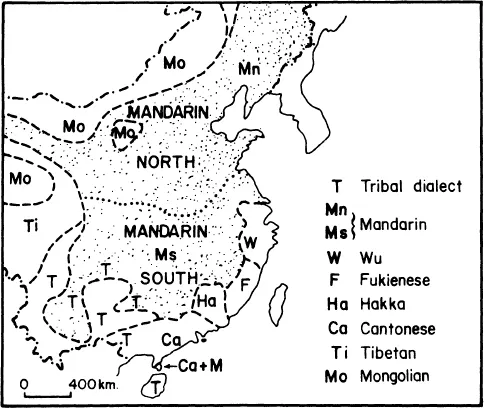

The long-standing identity of the Chinese nation has arisen from the early distinctiveness of their unique civilization, setting them clearly apart from the peoples around them, whom they regarded as grossly inferior. The development of an ideographic script (representing not sounds but concepts) has meant that, however divergent the local spoken vernacular, the written symbols are intelligible throughout the vast territory (Fig. 1.1). Though north and south cannot understand each other in speech, they can do so in writing. For the small educated class, the intelligentsia of the administration, this was a valuable tool, but the complexity of the script hindered the spread of literacy. For an industrializing country, this has been a serious drawback, so the Chinese are now faced with the monumental task of developing a common spoken language, primarily based on the northern dialects, notably that of Peking (the seat of political power). At the same time, to ease dissemination of literacy, they are attempting to replace the ideographic script by an alphabetic romanization of the written language, though because Chinese is strongly tonal in character, this is a daunting task.

Figure 1.1 Languages of China.

Adapted from Admiralty Handbook, China, vol. I, London 1944

Attainment of independence can present problems of finding a suitable official language to replace that used by the displaced colonial authorities. The Irish Free State in 1922 set out to create a separate Irish identity after centuries of English rule and felt language was an important medium in the task. During the long English domination the Irish Celtic tongue had become a minority language, losing its literary tradition and retreating to the remoter parts. A resurrected and revivified Irish language was introduced into the education system and a vigorous attempt made to force its use through government agencies. Nevertheless, after sixty years, the population remains overwhelmingly English-speaking, perhaps reflecting the strength of commercial and other ties with the rest of the English-speaking world.

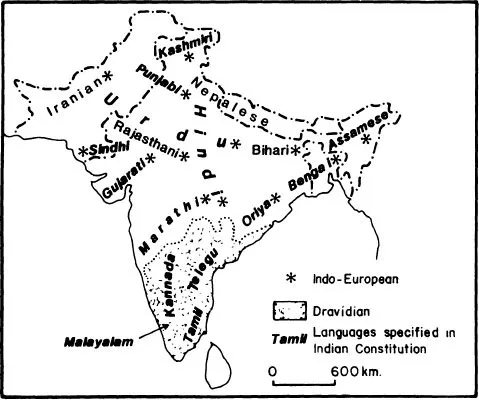

Efforts to create a sense of national unity, if not a single identity, in India since Independence have been bedevilled by the language issue. Despite the great number of languages spoken, six of them account for two-thirds of the population, while well over 90 per cent of the people are encompassed by the fourteen ‘languages of India’ defined in the Constitution. Such linguistic diversity has been seen as posing a primary threat to national cohesion, especially as no one language is spoken by sufficient people to give it undisputed superiority. Hindi or Urdu or other northern languages are, however, not readily acceptable to the quarter of the population using earlier Dravidian languages in the south (Fig. 1.2). Although the Constitution had recognised Hindi and thirteen other regional languages (four from the Dravidian family), there remained a need for one language to be a nationally recognized medium to replace the imperial lingua franca, English. Policy strongly favoured Hindi (used by just under a third of the population) in the Delhi dialect, support for which as the ‘official language of the union’ had been given by Gandhi. Nevertheless sectarian linguistic discontent caused civil disobedience, so the Delhi government, against its wishes, was forced to placate the regional interest by drawing internal territorial-administrative boundaries along linguistic lines. The government view has been that this has generated centrifugal forces when the need has been for centripetal ones in the interest of national economic and social welfare. English has been retained as an administrative language long after the original intention and Hindi’s role has been scaled down in the south. In the school system local languages are used, but Hindi is required at secondary level and above, while English is optional for government positions.

Figure 1.2 Languages of India.

Compiled from various sources

Switzerland is usually cited as an example that multilingual nations can be created, and there is no doubt that the Swiss are keenly aware of their common identity. Nevertheless Switzerland displays some special aspects, such as a federal state of a strikingly decentralized kind, allowing the cantons a substantial degree of fre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Introduction

- 1 The nation

- 2 The state

- 3 Territory

- 4 The frontier

- 5 Geographical aspects of national defence

- 6 Territorial administration

- 7 The rise and demise of empires

- 8 Aspects of international organization

- Selected bibliography

- Index