- 225 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Immobilized Enzymes for Food Processing

About this book

Much has been written about immobilized enzymes during this period of time. So much, in fact, that it can become difficult even for those involved in developing new enzymatic food processing operations to bridge the gap between the field of immobilized enzymes and their specific requirements. It is the purpose of this book to assist those engaged in this difficult task. It is also a goal to bring to the researcher in enzyme immobilization an appreciation for the requirements of the food processing industry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Immobilized Enzymes for Food Processing by Pitcher,Wayne H. Pitcher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction to Immobilized Enzymes

Wayne H. Pitcher

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- I. Introduction

- II. Adsorption

- III. Covalent Bonding

- IV. Entrapment

- References

I Introduction

The purpose of this chapter on enzyme immobilization is to introduce the reader to the diversity of immobilization techniques available and some of the variables that affect the actual immobilization procedures. No effort has been made to judge the suitability of these methods for immobilizing enzymes for food processing. These considerations are discussed in Chapter 3. It is not intended that this section necessarily be comprehensive or contain detailed descriptions of immobilization procedures. Since enzyme immobilization can be accomplished in numerous ways under so many sets of conditions, these details would, at best, only provide a starting point. What is important is that the reader understand the various options known to be available in order that he may be able to select a reasonable approach to his particular problem. Thus, the emphasis in this chapter is on the attributes of the various methods of immobilization and the ways in which workers in this field have attempted to vary them.

Although there are hundreds of immobilization procedures that have been categorized in various ways, for the purposes of this treatment of the subject they are placed into three general groups. These three types of immobilization are adsorption, covalent bonding, and entrapment. Such a classification is convenient, if somewhat arbitrary. There are cases where two methods are combined, a common example being adsorption and cross-linking (a form of covalent bonding). For more detailed information on enzyme immobilization, other references should be consulted.1,2 Some additional examples are also given in Chapter 4.

II Adsorption

Adsorption is the oldest of the techniques used to immobilize enzymes, dating back to 1916 when Nelson and Griffin3 used both charcoal and aluminum hydroxide to adsorb invertase. Since that time a wide range of organic and inorganic substances have been utilized as supports for adsorbed enzymes. Both organic materials such as charcoal, various cellulose derivatives, and ion exchange resins and inorganic materials including silica, alumina, titania, glass, and various naturally occurring minerals have been used.

Although adsorption has had a dubious reputation in the past, probably as a result of problems with desorption and inactivation upon adsorption, commercially it has seen relatively frequent usage. Clinton Corn Processing Company has reported using DEAE-cellulose to adsorb glucose isomerase.4 Tanabe Seiyaku Company has been immobilizing aminoacylase on DEAE-sephadex and other ion exchange resins for use in a process to racemize mixtures of D- and L-isomers of amino acids.5 CPC-International is adsorbing glucose isomerase to porous alumina beads via a process developed by Corning Glass Works.

Development of a useful adsorbed enzyme derivative depends on many factors. Perhaps the most important, or at least the first to be encountered, is the interaction between the enzyme and the surface of the carrier.

The same enzyme will be adsorbed on different carriers to varying degrees and exhibit different levels of activity as a function of the support material properties. Similarly, a carrier which is effective for one enzyme may be totally useless for another.

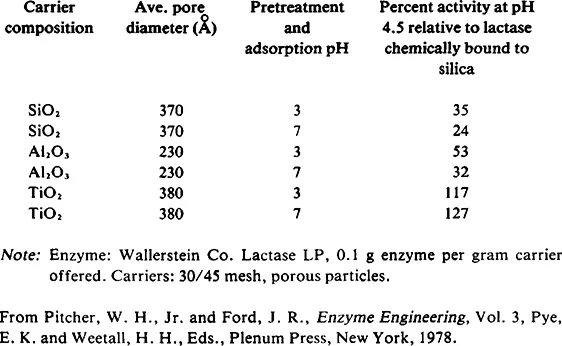

Several striking examples of the effect of carrier composition on adsorbed enzyme activity have been reported. Pitcher and Ford6 adsorbed /3-galactosidase (lactase) onto various porous ceramic beads with widely varying results as shown in Table 1. Stanley and Palter7 reported adsorbing this same enzyme on a wide range of phenol resins. They found that several materials including Duolite® A-1 (Diamond Shamrock Co.), charcoal, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, salicylaldehyde, and o-cresol-phenol-formaldehyde polymer failed to retain any enzyme activity. Oxidized catechol, humic acid, phloro-glucinol-formaldehyde polymer, and catechol-formaldehyde polymer exhibited good initial activity but exhibited significantly lower activity after treatment with salt solution. Duolite® S-30 (Diamond Shamrock Co.), resorcinol-formaldehyde polymer, and Duolite® S-30 formylated with DMF-POCl3 showed relatively high activity retention even after soaking in 2MNaCl or 4M urea for several hours. The authors did eventually resort to glutaraldehyde cross-linking to stabilize the composite after adsorbing the enzyme to the S-30 resin.

Table 1 Lactase Adsorption

Caldwell et al.8 reported affecting the activity of a β-amylase-Sepharose 6B derivative by varying the hexyl-group substitution levels in the sepharose. Maximum activity was observed at a hexyl to galactose residue molar ratio of 0.5.

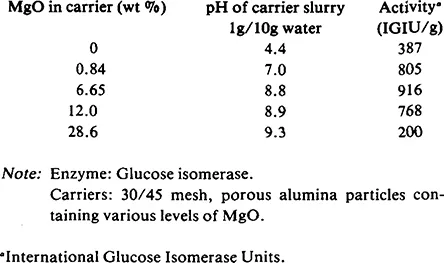

A patent granted to Eaton and Messing9 describes the effect of varying amounts of magnesia in a porous alumina carrier on the activity of adsorbed glucose isomerase. Addition of magnesia to the alumina support composition affects pH which may, in turn, influence enzyme activity. From Table 2, it can be seen that enzyme activity falls off at low and high MgO levels. Other data in the patent indicates the optimal magnesia level to be in the 1 to 4% range.

Some of the effects of carrier composition in this case may be attributable to pH shifts. Examples of pH effects on enzyme adsorption are well known. Kennedy and Kay10 reported optimal adsorption of dextranase on porous titanium oxide spheres at pH 5.0. This derivative was evidently at least fairly stable when used in a column reactor. However, when the pH of the dextran solution feed was raised from 5.0 to 7.3, enzyme was rapidly eluted from the titania bed.

Boudrant and Cheftel11 reported on the stability of invertase adsorbed to several macroreticular ion exchange resins. Enzyme desorption was more pronounced at pH 5.9 to 6.3 than at lower pH (2.4 to 3). However, other conditions such as temperature and ionic strength more strongly influenced enzyme desorption.

High ionic strength solutions of electrolytes do tend to cause the desorption of adsorbed proteins. The extent of this problem depends on the specific enzyme and support material involved, pH, temperature, and perhaps other variables. Boudrant and Cheftel,11 and Stanley and Palter,17 and Baratti et al.12 all reported the effect of ionic concentration on the adsorption of enzymes as had many others before them. Each of these groups, however, also reported other factors having even greater influence on the susceptibility of the immobilized enzyme to desorption. Boudrant and Cheftel11 observed marked variation in enzyme adsorption with pH. Stanley and Palter7 reported wide variations in enzyme adsorption as a function of the support material. Baratti et al.12 observed that different sodium chloride concentrations affected the adsorption of two different enzymes on the same DEAE-cellulose support. Less than 20% of catalase was adsorbed from 0.1 M NaCl solution, while more than 90% methanol oxidase was adsorbed. A patent by Cayle13 describes specific adsorption of β-galactosidase from a crude enzyme preparation onto aluminum silicate at a pH between 3 and 6 and desorption at a pH between 7 and 8. In other words, knowledge of the enzyme-support interaction as a function of adsorption conditions can be utilized for enzyme purification as well as enzyme immobilization.

Table 2 Glucose Isomerase Adsorption9

Other factors are also important in the adsorption of enzymes to support materials. These include the duration of enzyme-support contact, enzyme to support ratio, and enzyme concentration. Temperature can also influence adsorption but this usually is not readily apparent in systems of interest where adsorption is normally strong and temperature ranges are relatively small.

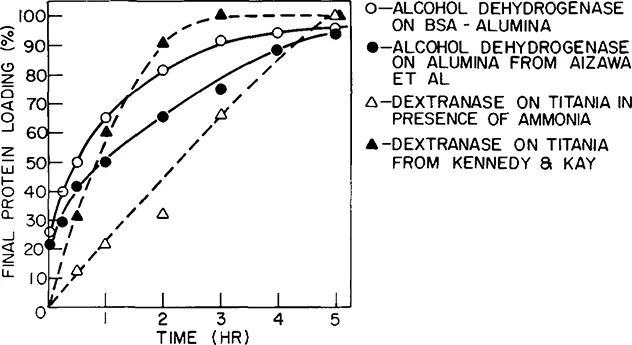

Enzyme adsorption seems to require a longer time than would be expected solely from diffusion rate considerations. Typical enzyme uptake curves are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that the adsorption rate can be affected by the support properties and adsorption conditions, further evidence that the adsorption reaction itself is the rate-limiting step. In the absence of enzyme adsorption rate data, it is usually prudent to allow 16 to 24 hr contacting time for the preparation of an adsorbed enzyme derivative.

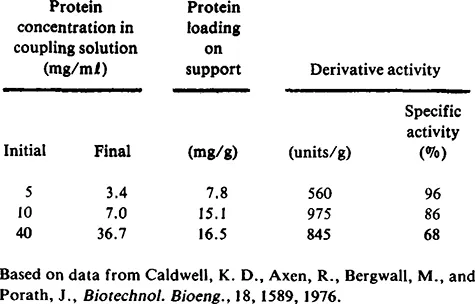

Another commonly observed phenomenon is illustrated by Table 3 based on data from Caldwell et al.8 From this table it is apparent that the higher the enzyme or protein concentration, the higher the loading. Concentration, not amount, was the critical factor since excess protein was available in all cases. It is also clear that at high enzyme concentration the support material becomes saturated and little additional protein can be adsorbed even at higher concentrations. Finally, the specific activity decreases with increasing enzyme loading, even to the extent that lower total activity is observed for the derivative. This phenomenon has been observed, even more dramatically in other cases. It is apparent that simply adsorbing a large amount of enzyme on a support material is not sufficient to produce a high activity derivative. Kennedy and Kay10 reported a higher protein loading on titania when they attempted to adsorb dex-tranase in the presence of ammonia. However, when they used no ammonia, the titania derivative had lower protein loading (3.2 vs. 25.1 mg/g matrix), but much higher activity (9.6 vs. 2.2 units/g).

Figure 1 Enzyme adsorption as a function of time.

Table 3 Amyloglucosidase Adsorption on Hexyl-Sepharose

The apparent activity of an adsorbed enzyme derivative has frequently been observed to rise as smaller support particles are used. Usually this phenomenon is attributed to internal diffusion limitations and indeed that is frequently the case. However, at least in the case of adsorbed enzymes there is another effect that is sometimes overlooked. Enzyme loading itself can vary with particle size.

One might expect to observe higher enzyme loading on small vs. large particles from a sample of various size particles contacted with enzyme at the same time. Diffusion effects would favor the smaller particles. However, at Corning Glass Works, enzyme was adsorbed on two separate porous alumina samples, one 30/45 mesh and the other 50/60, under identical conditions. The protein loading on the 30/45 mesh material was 20.8 mg/g and on the 50/60 mesh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction to Immobilized Enzymes

- Chapter 2 Immobilized Enzymes for Food Processing

- Chapter 3 Requirements Unique to the Food and Beverage Industry

- Chapter 4 Manufacture of High Fructose Corn Syrup Using Immobilized Glucose Isomerase

- Chapter 5 Potential and Use of Immobilized Carbohydrases

- Chapter 6 Applications of Lactase and Immobilized Lactase

- Chapter 7 Immobilized Proteases — Potential Application

- Chapter 8 Application and Potential of other Enzymes in food Processing

- Index