1

A Lens on the Unremarkable

The unremarkable is actually remarkable. Much of children’s everyday text making is apparently unexceptional: a swift drawing dashed off in a few moments, a routine classroom exercise, exchanging messages, copying from the class whiteboard. Yet, viewed through a certain lens, what children do as a matter of course becomes surprising. Ordinariness masks richness and complexity, routine features that pass by largely unnoticed are not at all trivial and commonplace ‘errors’, even if not overlooked, are replete with meaningfulness. What might appear mundane, effortless, mistaken, even uninteresting, turns out to be intriguing.

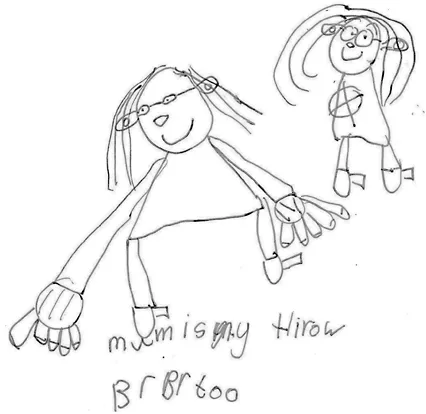

The quintessence of ordinariness, a text made at home by Shakira (age 6 years) epitomizes the remarkable in the unremarkable (Figure 1.1). Her drawings of frontally-oriented people are readily recognizable, but why are they different sizes? On the enlarged hands, Shakira included palm lines or traces of bones, but elsewhere she omitted other details such as the colour, texture and style of clothing, and background. Why did she do this? Arms are omitted on the smaller figure, even though Shakira knew how to draw them (see also Cox, 1992: 41–42; Golomb, 1974: 104; Goodnow, 1977: 65). Is this a mistake? Where the proportions of drawing do not match those of the actual world and where certain features are not incorportaed, a possible inference is deficiency: either mistakenness in how children see the world or immaturity in their drawing skills. Could there be an alternative explanation? The caption—‘Mum is my Hirow (Hero) Br Br (Barbara) too’—might raise a smile, but what about the ‘incorrect’ spellings and omission of punctuation marks? Is this inability or immaturity, or can it be seen in a different way? Yet other questions arise. Why did Shakira choose the present tense? Why did she position her writing one block above the other, and below the drawing of her mother? Why does ‘Hirow’ reside in writing rather than drawing? She drew and wrote with green glitter pen and trimmed the sheet with chopped cuts to remove extraneous paper. Is this meaningful? An entirely everyday text such as this raises issues central to investigation of the unremarkable. What is and is not noticed, who notices, and why?

THE IDEOLOGY OF THE LENS

Whilst by no means denying that children develop physically and that they learn increasingly about the world and being in the world, the dominant view that they progress from asociality to sociality, from simplicity to complexity, from irrationality to rationality and from incompetence to competence has proven ‘extraordinarily resistant to criticism’ (Prout and James, 1997: 22). This is only one step away from slippage into seeing children as deficient. Of course, they do not have adults’ breadth of social experience, and they have many years of school education ahead of them. Even so, discourses of inadequacy, shortcoming and ignorance focus on what children cannot do. Viewing them as in need of improvement, correction or ‘filling up’ distracts attention from the sophistication of what they can do and the range of what they do know.

Regarding children as social agents shifts the focus. It takes seriously their ‘work’ as they participate in the environments in which they find themselves. Social roles, relationships and interactions are generated in the dynamism of people engaging with one another, and this includes children. Of course, young people’s lives are shaped and constrained, even determined, by adults. Yet, as they participate in everyday social activities—whether interacting around the kitchen table, working in the classroom, playing in the park, shopping, or whatever else—what goes on is not just a case of social determinism. Children frame, interpret and respond. Doing what is expected of them takes social and semiotic effort as they figure out what is needed on this occasion. Children are not merely compliant respondents. Their very engagement as they weigh up, abide by, oppose and negotiate exchange with others both sustains, reproduces and challenges existing discourses and practices. The well-established and highly particularized rules and social relations of school construct one such space where young people both conform and contest. Children act upon the powerful ideologies of what is done and how (Hutchby and Moran-Ellis, 1998; James, Jenks and Prout, 1998; Prout and James, 1997). This marks a shift from socialization to disposition, from ‘being done to’ to participation.

Common parlance, the well-established term ‘acquisition’ (e.g. ‘language acquisition’, ‘knowledge acquisition’, ‘skills acquisition’) implies that children learn through osmosis, just as the pedagogic notion of ‘delivery’ presupposes largely uninterrupted ‘reception’. The notions of transmission and assimilation background agency, with an attendant positioning of children as absorbers of knowledge and experience. An alternative is that learning requires semiotic effort. Something is attended to, be it a new-born baby recognizing the reaching out of a hand, a preschooler working out the rules of tense or plurality (e.g. ‘I goed’, ‘the feets’), a beginning reader making sense of the shapes of script or a school scientist puzzling over the use of arrows to show magnetic force. An alternative to passivity is engagement and ‘work’.

Representation and communication are never ideologically neutral (Halliday, 1978; Hodge and Kress, 1988; Lemke, 1990). What and how children draw and write are framed by what is valued, and what is valued in one social environment might be denigrated, ignored or reconfigured in another. This shapes what they are asked, expected or choose to do, how their efforts are received and how their texts are evaluated. The ideology of the lens—how texts are looked at—frames what is recognized. This is highly political because what is acknowledged shapes how young people are positioned, whether as social agents or as developmentally deficient, or whatever else. Even from the youngest age, how children are seen and how they come to see themselves as text makers are formative of their dispositions and identities. Societal and educational discourses and practices have far reaching implications not only for what it means to be literate, and more broadly an assured text maker, but also for citizenship and social justice.

A LENS ON THE UNREMARKABLE IN CHILDREN’S DRAWING AND WRITING

The so-called ‘scribble’ produced by very young children was formerly— and sometimes still is—considered to be motor action undertaken and enjoyed for its own sake, ‘chaotic’ and devoid of representational intentionality (Matthews, 1999: 4), even ‘meaningless’. This has led to the commonly held view that their drawings are deficient. More recent research shows that intense multidirectional lines, shading of areas or ‘patches’ can represent the solidity of people, animals or make-believe characters (Buckham, 1994: 134–137) or inanimate objects (Matthews, 1999: 34). Different kinds of marks (looped and single lines or ‘slashes’ and zigzags) can show existence, number and location, and body parts may be represented discretely rather than connected (Lancaster, 2007; Wolf and Perry, 1988: 20). Pre-schoolers’ representations can depict sensations such as a hurting knee or tactility such as the feel of a blanket (Brittain, 1979: 30, 33). It is not that this is wrong. Even if unlike the drawing of older children, these are marks of meaning, neither haphazard nor accidental, but ‘principled’ (a term I borrow from Gunther Kress here and throughout the book). In order to show the defining attributes of people, animals and objects, a common feature of early drawing is that children may not restrict themselves to one angle only. It is not that representations with multiple viewpoints are any less sophisticated than a single perspective, or that there is an historical or developmental progression from one to the other (see also Cox, 2005; Golomb, 1999). In drawing without one fixed point of view, such as a family around the dining table (Matthews, 1999: 84–93), a friend on the other side of the street (Lowenfeld and Brittain, 1987: 269) or children in a circle enacting a playground rhyme (Cox, 1992: 137), angle is a semiotic resource that provides the potential for making certain meanings.

What if what is commonly assumed to be mistaken is looked at again? As 4-year-olds moved between writing-like squiggles and meticulously formed lettering, this was not a case of a linear progression from ‘scribble’ to ‘proper writing’ (Kenner, 2000b: 254–264), or ‘reverting’ to immaturity. Rather, their representations were shaped by purpose. Fluent inscription of a linear succession of circular shapes was an act of writerly performance, with the visual appearance of continuousness being deemed apt for a story and horizontal completion of a grid-like structure being well suited to signifying a class register. On the other hand, careful attention to the detail of the Arabic script was a way of demonstrating seriousness in engaging with alphabetic form. As they observe and participate in text-making activities, children gain access to and make meaning with an ever-widening range of resources. This shifts the focus to which resources children have available to them and how they deploy them at their discretion within the framing of specific activities.

Literacy is highly valued in many contemporary societies. Spelling— where the script is alphabetic—maintains a key place in contemporary policy, curriculum, teaching and assessment. We want children to be able to spell competently, because this equips them with the resources to participate confidently in different social domains. As they learn the rules and irregularities of Standard English spelling, they do not always ‘get it right’. Shakira wrote ‘Hirow’ instead of ‘hero’ and ‘BrBr’ instead of ‘Barbara’ (Figure 1.1). How is this to be understood and handled? One response is to say that it is a good attempt for a child of this age, but that some of the spellings are plain wrong and will be rectified in time, with instruction, correction and practice. Alternatively, features that might be judged inaccurate can be seen as being replete with resourcefulness. Where children are taught to identify phonemes and to ‘build’ words using phonics, Shakira’s spellings represent a principled effort to transcribe the sounds of speech. Inadequacy is replaced by resourcefulness and agency. Even so, teachers are responsible for supporting children towards what is valued educationally as set out in the requirements of the curriculum, which includes learning to spell correctly. This raises questions around how learning opportunities are designed and how children’s efforts are responded to. The desired outcome remains educationally and societally valued, but the process of getting there comes to the fore.

Over the course of their schooling, children learn to create a range of genres: stories, poems, reports, lists, instructions and so on. As they move between different subjects of the curriculum, learning to interpret and represent graphically the specialized knowledge of each subject area according to its particular and shared representational conventions is not without challenge (Gee, 2003; Unsworth, 2001). The co-presence of narrative, map and game in the same text (Barrs, 1988; Pahl, 2001) might be judged as flawed. In certain contexts, this would be the case. Made at home as part of self-generated activities, such texts may be generically mixed, but are they a muddle? As children transport representational resources between school and home, they make the most of familiar and newly discovered forms in their shaping of meaning. They also integrate features of contemporary popular culture such as characters and events from digital games, comics, cartoons and films (e.g. Dyson, 2008; Marsh and Millard, 2000) in ways that do not necessarily cohere with formal genres. Viewed not as deficiency but as resourcefulness, this demonstrates initiative as children make the most of what is to hand in investigating forms and structures, and discourses and genres. It is important that children learn to create texts that conform to convention. Given the space to explore and experiment, we see the inventiveness, originality and ingenuity of their drawing and writing.

Change has been intense in recent times, with upheavals on an unprecedented and unforeseen scale. Stabilities in finance, employment, national and global politics and social relationships have been undone in quite unanticipated ways. Along with this, text-making practices unthought of fifty years ago have become commonplace and un-extraordinary. With increasing affordability of, and access to, an ever-widening range of digital technologies in many contemporary societies, children play video games, surf the web, shop online, download music, exchange online messages, blog, make web pages, and post photographs and movies (Carrington, 2005; Downes, 2002; Facer, 2003; Holloway and Valentine, 2003; Knobel, 2006; Livingstone and Bovill, 2001). Commonplace and un-extraordinary, these forms of, and practices in, authorship, dissemination and interaction have transformed communicational possibilities, and are redefining literacy (Carrington, 2004; Lankshear and Knobel, 2003). Indeed, current debate questions whether ‘digital literacy’ is sufficient to account for expanding multimodal forms of text making.

A LENS FOR INVESTIGATING CHILDREN’S DRAWING AND WRITING

Social semiotics is concerned with signs, sign making and sign makers. The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, one of the founders of semiotics, proposed that a sign is a ‘double entity’ comprising a signifier and a signified (Saussure, 1966: 65). In his study of the spoken sounds of Indo-European languages, this duality, he argues, does not consist of a naming word corresponding to the thing it names but respectively to a ‘sound-image’ produced physically and a ‘concept’ constructed in the mind: the physiological and the psychological (ibid.: 66). Beyond the signifiers of speech that interested Saussure, the social semiotic notion of ‘resource’ embraces all modes of representation and communication (e.g. writing, drawing, gesture, gaze, dress, etc.). Sign making is embodied, not just ‘mindful’. Replacement of ‘concept’ with ‘meaning’ broadens the scope of what can be signified to include, for example, the affective, attitudes and perspectives—and the social. A coherent theoretical and analytical framework unrestricted to any one mode provides a means for examining representation and communication irrespective of what it is.

For the most part, children’s writing and drawing have been studied separately, the former mainly by language and literacy specialists, and the latter largely by developmental and cognitive psychologists, and art educators. As a consequence, much is known about writing and drawing discretely. Their co-presence in children’s text making has been by no means ignored in research. With the recent emergence of multimodality as a domain of inquiry, writing and drawing have been examined as inter-semiotic rather merely co-present, with implications for design, the representation of knowledge and the construction of identity (e.g. Bearne, 2003; Mavers, 2009; Pahl, 2004). Multimodal texts are ensembles made with the resources of more than one mode. Settling on whether writing or drawing is best suited to purpose demands resolutions with regard to the distribution of meanings and the relationships between them.

At first sight, different kinds of graphic texts—a drawing, copying from a picture dictionary, digital exchange—appear to have little in common. They entail different modes of representation, different media, different identities, different purposes, different environments, and no doubt other things too. If representation is taken to consist of form and meaning (or ‘sign’) then certain questions can be asked irrespective of what it is. How are signs made in a range of ways? Why was this mode chosen for this sign making? What would have been the consequences of choosing a different mode? Can the same meaning be expressed in different ways, or are certain meanings exclusive to either writing or drawing? As graphic forms of representation, are any resources shared? Where is the semiotic load? What has been put with what? What relationships have been constructed between modes? In their handling of a variety of resources in their shaping of meaning, what does this imply about children as makers of texts?

In investigating the unremarkable features of children’s drawing and writing as agentive design, a theory of representation must be able to offer a means of accounting for the routine and commonplace, including ‘errors’, as investment of ‘work’. It was Saussure’s view that the relationship between signifier (signifiant) and signified (signifié) in a word sign is generally arbitrary in the sense that the sounds of speech bear no relation to what the thing being referred to is (Saussure, 1966: 67, 73). Notwithstanding the etymology of word roots, of which children are unlikely to be aware, there appears to be some sense in the contention that the marks of writing bear no visual relation to the actual things they represent. This, however, is an observation on the extent to which the form of a signifier has ‘resemblance’ to that which it signifies. What if the focus shifts to semiotic (sign-making) processes? A social semiotic approach maintains that people do not use ready-made signs; they make them (Kress, 1993, 1997). This perspective challenges the commonly held view that culturally developed and socially enforced codes are acquired and applied. In an entirely ordinary process, signs are constantly made afresh as composites of form (or signifier) and meaning (or signified). Even though the sign maker produces meaning with well-acknowledged and r...