![]()

Part I

Tears and Image

![]()

1 Women Mourners in Byzantine Art, Literature, and Society

Henry Maguire

The principal purpose of this chapter is to examine attitudes toward mourning practices in Byzantium, especially as revealed in the art and literature of the Church.1 However, my chapter also has a secondary purpose, which is somewhat broader in its implications, namely, to address the problems associated with the use of medieval religious art as evidence for social history.

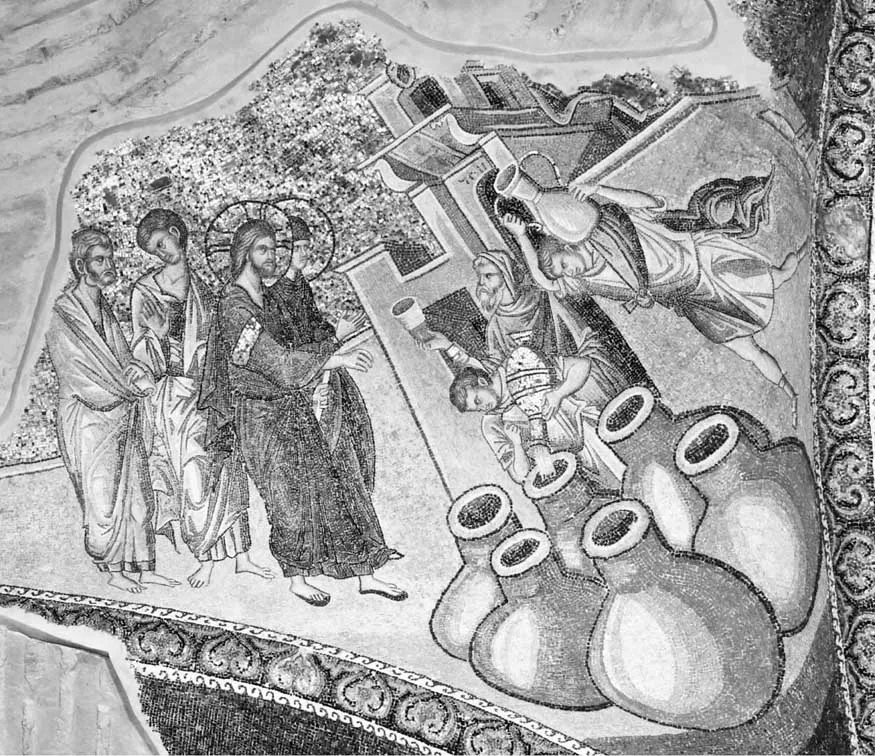

It is obvious to the most casual observer that there are limits to the extent to which Byzantine paintings and mosaics can be used as historical sources. We may take, as an example, the early fourteenth-century mosaic from the exonarthex of the Kariye Camii in Istanbul (Figure 1.1).2

Figure 1.1 Istanbul, Kariye Camii, Mosaic. Wedding at Cana.

Source: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Photograph and Fieldwork Archives, Washington, DC.

It depicts Christ turning water into wine at the wedding of Cana. As has been shown by Charalambos Bakirtzis, the vessel carried on the shoulder of the servant on the right is a particular type of container with a spherical or ovoid body known to the Byzantines as a Lagena.3 This type of vessel seems to have first appeared in the ninth century, and, as we know from archaeological evidence, was still in use in the fourteenth century. The Lagenes were employed both for the transport of liquids, and, as we see in the mosaic, for their handling in the household. The mosaic in the Kariye Camii, therefore, appears to give us valuable clues concerning the shapes of medieval Byzantine ceramics and about the ways in which they were carried and used. On the other hand, the same could never be said of the clothing worn by the actors in the mosaic. The classicizing garments of the disciples behind Christ, for example, follow an artistic tradition that goes back to the beginnings of Christian art in late antiquity. No one could suppose that they reflect the kind of costumes that might have been worn at a Byzantine wedding in the fourteenth century.

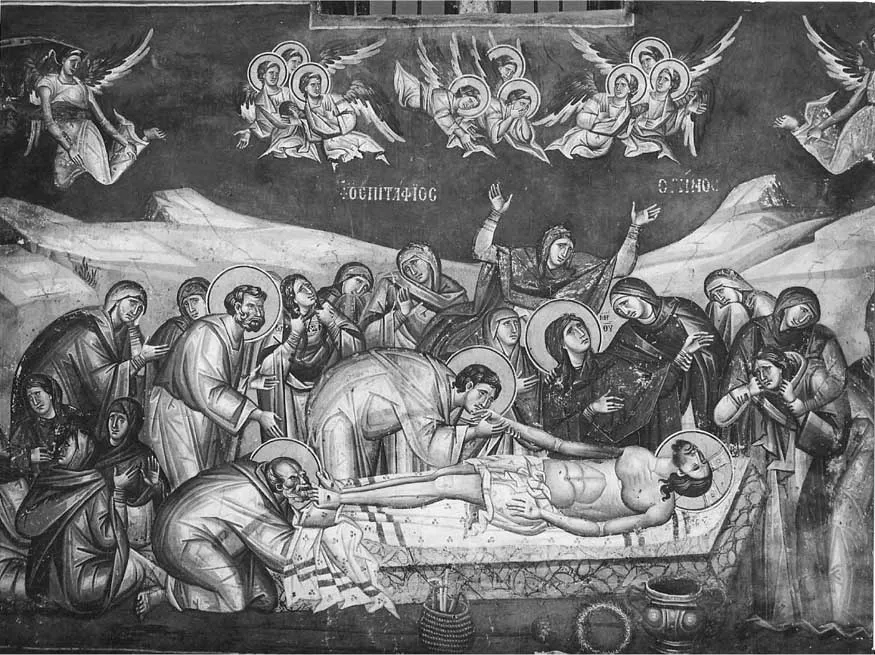

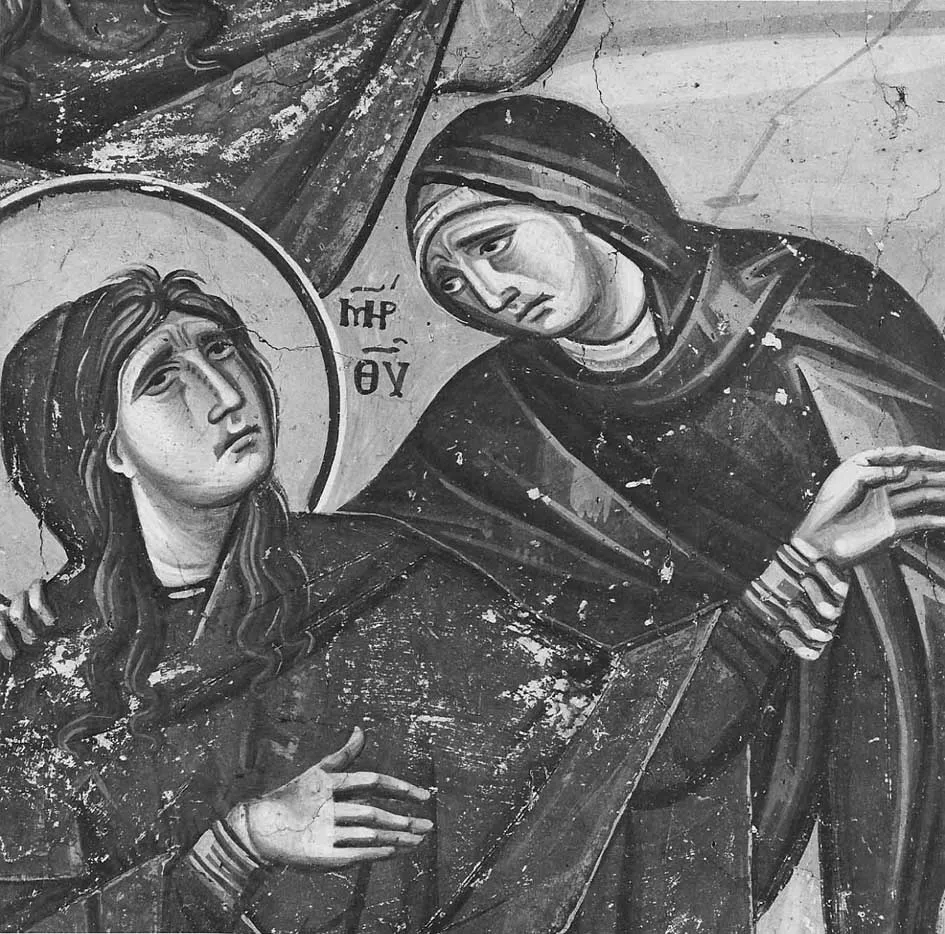

Medieval Byzantine religious art, therefore, turns out to be an uncertain guide to the reconstruction of objects used in daily life, useful in some particulars, but not in others.4 But to what extent can Byzantine paintings be used as evidence for the performance of popular rituals in Byzantium?5 A case in point is the wonderfully detailed fresco of the Lamentation over the dead Christ from the church of St. Clement at Ohrid, which was painted by the Greek artists Michael and Eutychios in the last decade of the thirteenth century (Figures 1.2–1.3).6

Figure 1.2 Ohrid, St. Clement, fresco. The Lamentation.

Photo: Josephine Powell Photograph, courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Figure 1.3 Ohrid, St. Clement, fresco. The Lamentation, detail of the Virgin.

Photo: Josephine Powell Photograph, courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Here we see a large crowd of female mourners, who make a variety of gestures of lamentation: they bare their heads, they expose their hair, they pull their locks, or they raise their arms into the air. Are we justified in seeing this scene as an illustration of a ritual lament of the late thirteenth century, just as the vessels in the Wedding at Cana in the Kariye Camii were faithful renderings of medieval ceramics? Or are these mourning women merely part of an independent iconographic tradition that had no connection with contemporary reality, like the costumes of the disciples in the mosaic of the marriage at Cana?

In order to find an answer to this question, I shall divide my chapter into two sections. In the first section, I shall outline the church’s official attitude to mourning, as expressed in sermons, letters, and biblical commentaries. In the second section, I shall look at some representations of mourning in Byzantine art, in order to see how far these may have corresponded with church teaching, on the one hand, and with actual social practices, on the other.

MOURNING IN CHURCH WRITINGS

From the fourth century onwards, the teaching of the Byzantine church on the subject of mourning was consistent: mourning was a proper response to bereavement, but only in moderation. The strictures of the ecclesiastics were directed in the first place to women, since women took the primary role in the mourning rituals of Byzantium. However, men were not excluded from displays of grief, as we learn, for example, from the Life of St. Mary the Younger, a pious woman of the ninth century. When this saint died, we are told that “there broke forth great weeping and wailing, raised both by her husband and the women.”7 Weeping was permitted, but excessive demonstrations of grief, such as tearing one’s hair, clothes, or cheeks, loud wailing, or beating one’s chest were unacceptable, not just because they were indecorous, but more importantly because they implied a lack of faith. The problem of what was correct deportment for Christians in bereavement was often discussed in commentaries upon the eleventh chapter of St. John’s Gospel, which tells the story of the Raising of Lazarus. The death of Lazarus, of course, was the one occasion on which the Bible says outright that Jesus himself wept.8 St. John Chrysostom, in his commentary on this passage, compared the restraint of Mary and Martha with the abandon of the women of his own time: “but now,” he said, “along with the other evils, this female affliction also prevails. For in lamenting and wailing they make a display, baring their arms, tearing their hair, scratching gullies down their cheeks. … And they bare their arms—this under the eyes of men. … [Weeping] I do not forbid,” continues John Chrysostom, “but I forbid beating oneself and immoderate weeping. … Weep, but gently, but with decorum. … If you were to weep thus, you would not weep as one who distrusts the Resurrection, but as one who cannot bear being separated.”9 The same advice was repeated by other fourth-century fathers, including St, Basil of Caesarea and St. Gregory of Nazianzus,10 and also by many later Byzantine writers. Theodore of Stoudios (d. 826), for example, wrote to a nun whose mother had recently died, praising her for “not giving vent to irrational wails and desperate lamentings.”11 To be altogether without grief, he said, shows want of feeling, but to break down in grief shows a lack of faith in the Resurrection.12

In a similar vein, we may quote from the commentary on St. John’s Gospel that was written by Theophylaktos of Bulgaria (d. after 1126), probably for the Empress Maria, wife of Michael VII. Speaking of the Raising of Lazarus, Theophylaktos declared: “To have no feeling and no weeping is bestial; but to weep too much and to be fond of lamenting is womanly.”13 A somewhat later commentator, Euthymios Zigabenos (ca. 1100), drew a lesson concerning the correct mode of grieving from Christ’s demeanor at the death of Lazarus: “Christ wept, allowing his [human] nature to reveal what was proper to it, giving us a moderate measure of weeping for the dead. Then Christ rebuked his feelings, not allowing them to degenerate into excess.”14 The twelfth-century South Italian preacher Philagathos drew a distinction between weeping and wailing; the former was natural and permissible, the latter was to be curbed, as Christ himself had curbed his grief at the death of Lazarus.15

Similar official attitudes toward grief were expressed in the lives of Byzantine saints. An example is found in the Vita of St. Mary the Younger, whose firstborn child, a son, died prematurely at the age of five. We are told that “her mother’s heart was broken and torn asunder, as one would expect; but she kept to herself, sighing and openly weeping, without, however, displaying unseemly behavior. She did not tear out her hair, nor did she disfigure her cheeks with her hands, nor did she rend her clothes, nor did she throw ashes on her head, nor did she utter blasphemous words. She almost conquered nature … weeping just enough to show she was a mother.”16

MOURNING IN BYZANTINE ART

For many centuries the teaching of the church with regard to mourning was reinforced by its art. Until the end of the twelfth century violent gestures of grief, such as the pulling of hair, the scratching of cheeks, and the tearing of clothes, were excluded from New Testament scenes.17 We may take, by way of example, the early twelfth-century fresco of the Raising of Lazarus in the Church of the Virgin at Asinou, on Cyprus, where the deportment of Christ and of the two sisters, Mary and Martha, corresponds admirably to the restraint prescribed by the homilists (Figure 1.4).18

Figure 1.4 Asinou, Church of the Panagia Phorbiotissa, fresco. The Raising of Lazarus.

Photo: Dumbarton Oaks, Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives, Washington, DC.

Only one of the women, Mary, holds her hand against her cheek, as a sign that she is gently weeping. Likewise, if we look at the painting of the Death of the Virgin (Koimesis) in the same church, we see that both the apostles and the women in the arcaded galleries behind them are weeping quietly, with their cheeks cradled in their hands or their garments.19 Somewhat more expressive gestures of grief can be found in twelfth-century paintings of the Threnos, the Lament over the body of Christ, such as the fresco of 1191 in the church of St. George at Kurbinovo. Here one of the mourning women may be seen to raise up her hands in lamentation.20 But, to my knowledge, before the thirteenth century Byzantine artists never painted violent, self-destructive gestures of the kind condemned by the church fathers, even in depictions of the Threnos.

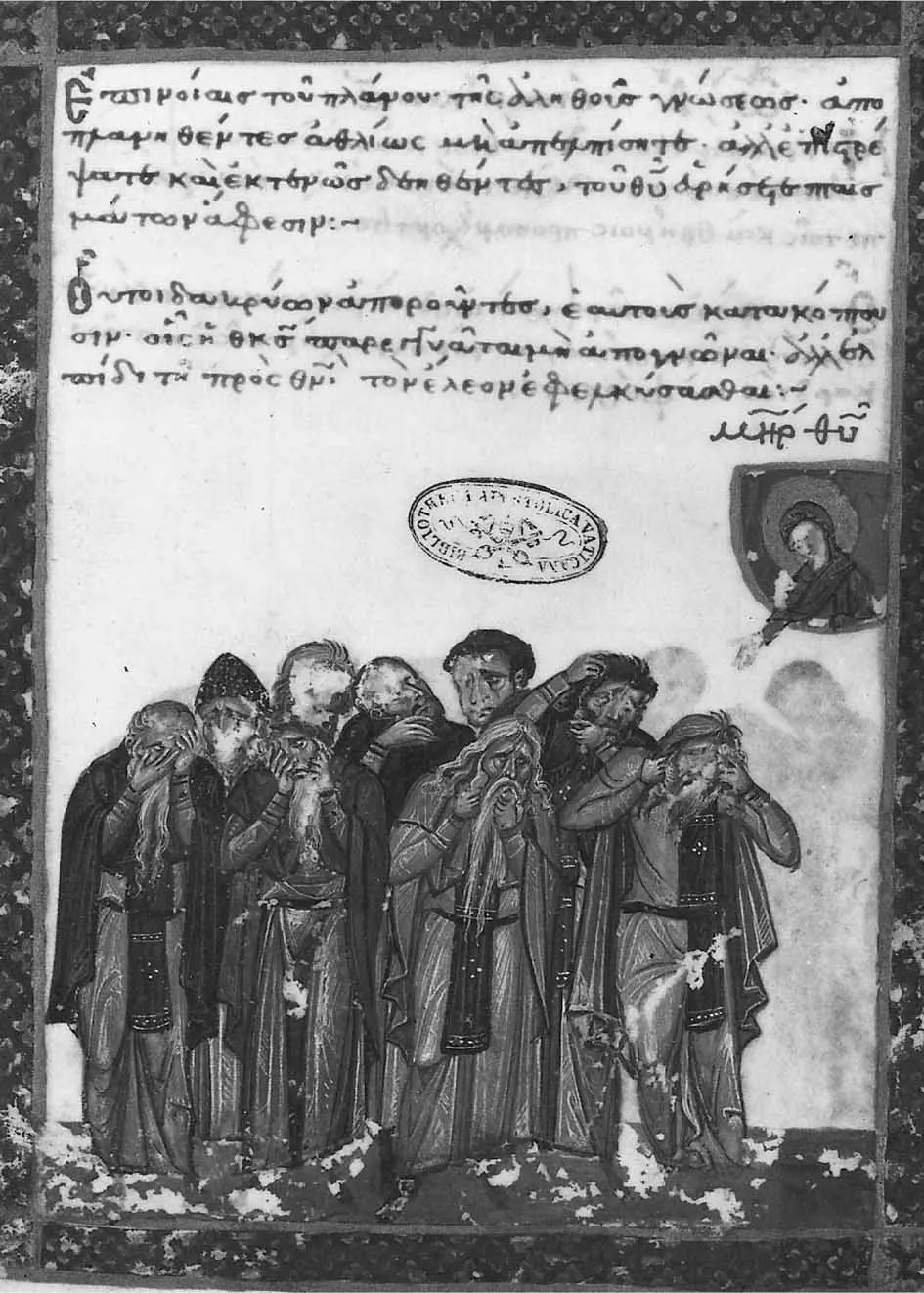

However, violent, unrestrained actions were described and depicted in other contexts, especially portrayals of penitents, deathbed scenes from the Old Testament, and the Massacre of the Innocents. In all these cases, extreme grief was permissible, even appropriate, according to the teaching of the church. St. John Chrysostom, while he discouraged lamenting for the dead, recommended that Christians grieve for their own sins.21 Accordingly, it is in portrayals of penitents that we find the most violent gestures of grief in Byzantine art, most notably in a miniature from a late twelfth-century or early thirteenth-century manuscript in the Vatican (ms. gr. 1754, fol. 6r.), which illustrates the Penitential Canon (Figure 1.5).22

Figure 1.5 Vatican Library, ms. gr. 1754, fol. 6r. Penitent Monks.

Photo: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Archivio Fotografico.

This poem, which was ascribed to Andrew of Crete, celebrates the “Holy Criminals,” whose prison is described in the Heavenly Ladder by ...