1 Legitimizing the new regime

The early post-revolutionary years

The establishment of the PRC in 1949 was the final step in an astonishing rise to power by the CCP (Wilson 1982, Saich 1996). Formed less than three decades earlier by a handful of men on a lake in Shanghai, the CCP overcame a number of seemingly insurmountable obstacles during its ascendancy. In 1927, the party’s fragile urban base was virtually wiped out by the nationalist Guomindang (KMT). On retreating to the rural province of Jiangxi, the party soon found itself under threat again by the KMT as well as aggressive regional warlords. During the ensuing search for a new base known as the Long March (1934–5) the party was repeatedly attacked by hostile minority groups and faced arduous terrain and severe weather conditions that accounted for well over 90 per cent of its membership. After travelling for over a year through 11 provinces and covering over 8,000 miles, the remnants of the party finally set up camp in the northern region of Yanan but with the KMT closing in once again the likelihood of survival appeared remote.

The threat of foreign imperialism also loomed large, mainly in the form of Japan which had colonized the whole of north east China (or Manchuria) and looked set to make further territorial advances. Although the eventual defeat of Japan in 1945 offered a temporary respite to the CCP, civil war between the communists and the nationalists broke out almost immediately, and with the United States providing financial and military support to the KMT, it seemed unlikely that the CCP could survive, especially in the absence of any support from Stalin and the Soviet Union. Against the odds, however, it was the CCP that triumphed four years later thanks mainly to a combination of KMT military incompetence and shrewd CCP military strategy (Eastman 1984, Pepper 1999).

Notwithstanding the impressiveness of the CCP’s ascendancy, outright victory was far from complete. The preceding decades of civil and foreign war, inept KMT administration and warlord factionalism, not to mention the absence of any central authority since the late nineteenth century, had inflicted deep wounds on China’s political and socio-economic system. To make matters worse, the ethnic minority provinces of Tibet, Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia had not succumbed to CCP control and pockets of KMT resistance continued in south western China for some months after the revolution. The scale of the task ahead was monumental. If the CCP was to rebuild China much was required from a party with little experience in local administration and none at all in national government.

But the party had another pressing issue to deal with as it emerged victorious after the revolution – that of how to legitimize its new-found authority. Whilst the success of the communist armed struggle did much to enhance the popular support (or revolutionary legitimacy) of the CCP especially amongst the peasantry who comprised over 80 per cent of the population, the party was in no position to become complacent. The euphoria of the revolution would not last for ever and if the party intended to retain its monopoly on power for any meaningful period of time, new and more durable sources of legitimacy were required. This chapter examines some of the principal modes of legitimacy employed by the CCP during the early period of its incumbency (1949–57).

Administrative control and legal rational legitimacy

One of the most pressing tasks of the early post-revolutionary period was the establishment of central administrative control over the entire country. Given the incompleteness of CCP rule in 1949, this needed to be a staged process which meant that for the first few years the PRC was governed by six regional administrative bodies (north west, north, north east, east, south west, central south). In the north and north east, civilian governments were set up without much difficulty due to the strength of the CCP in these areas and the successful completion of the various military campaigns. But in the other four regions where the party was not in full control it was necessary to temporarily accede administrative power to the party’s military wing, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) until the conditions were ripe for the local party-state to take over.

It was during this transitional period that the legal rational procedures of democratic centralism were first applied at a governmental level. As explained in the Introduction, in reaching a decision, party members are encouraged to discuss their opinions in an open and democratic manner without fear of retribution should they hold a minority view. A decision is reached by majority vote and once this is achieved all participants are expected to conform to the party line without dissent and without resort to irregular methods of overturning this line. We shall see later in this chapter how Mao was quick to violate this fundamental principle.

The hand over from military to civilian institutions occurred much sooner than expected and was relatively seamless. Although the military authorities (known as Military Control Commissions) enjoyed considerable autonomy as policy-making units during the transitional phase, their role was soon scaled down to that of co-ordinating the establishment of local civilian administrations, and by 1952 fully centralized institutions of party and government (or state) were put in place. Each was to be governed by its own constitution (1954 for the state, 1956 for the party) which set out, amongst other things, a detailed hierarchy of congresses (i.e. decision-making bodies) and a legal rational system of procedures for reaching decisions and for appointing and dismissing office holders.

The state structure

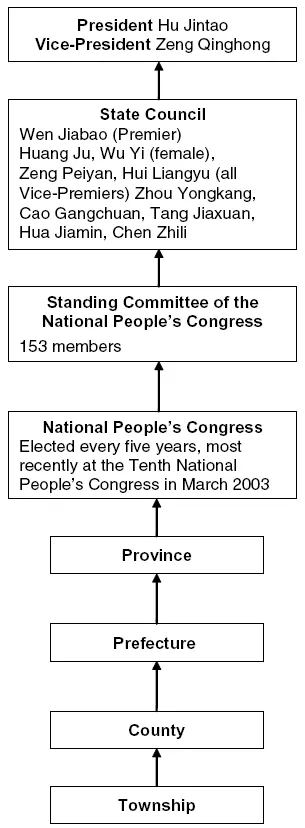

The structure of government, which remains in place today, comprises congresses at five ascending levels: national, provincial, prefectural, county and township (Schram 1987) (see Figure 1). During the early period, in accordance with the 1953 Election Law, representatives at the national down to the county level were elected indirectly (i.e. by congress members from the level immediately below them). So, for example, deputies at the national level, known as the National People’s Congress (NPC), were elected by members of provincial congresses, deputies to provincial congresses were elected by representatives of prefectural congresses and so on. By contrast, representatives at the township level were elected directly (i.e. by residents of that township).

Figure 1 Simplified structure of the Chinese government (2005).

According to Jacobs (1991: 173–4), in the state elections which took place during 1953–4 (the first in the PRC), 97 per cent of the population aged 18 and over were registered to vote and of them 86 per cent actually cast their vote. In the direct elections to the township congresses, votes were cast in large public meetings by a show of hands. In the indirect elections, lower level people’s congress members used secret ballots to vote for higher level people’s congress members. Yet, irrespective of which voting method was applied, there was no genuine choice of candidate because in every election the number of candidates always equalled the number of positions available.

The NPC is (theoretically) the supreme organ of legislative power. Comprising up to 3,000 delegates at any one time, its role is constitutionally defined as devising laws, amending the state constitution, ratifying international treatises and nominating or appointing senior state officials. The NPC is elected for a term of five years and holds one plenary session (or Plenum) each year. The unwieldy size of the NPC and the infrequency with which it meets means that it is unable to fully exercise its powers. It therefore elects a Standing Committee comprising about 150 members and this body acts on behalf of the NPC when it is not in session. Convening every two months (since 1987), the Standing Committee has gradually seen an increase in its law making powers and powers of supervision over the enforcement of the constitution. It also functions as an examination and approval authority for any proposed adjustments to the state budget and the fixed term plan for the national economy.

Yet, ultimate governmental authority lies with the State Council, officially the executive organ of the NPC but in reality also the state’s principal legislative body. Consisting of a small number of senior officials who meet frequently but secretly, it is the State Council rather than the NPC or the Standing Committee that formulates government policy and administrative measures. The State Council’s proposals are submitted to the Standing Committee for modification and then to the NPC for “consideration” (i.e. approval). The State Council also supervises the numerous policy commissions and ministries that now exist such as the State Economic and Trade Commission and the Ministry of Education. During the Mao era, the State Council was headed by a Chairman and a Vice-Chairman who were advised by a Premier and a number of Vice-Premiers. Following the 1978 state constitution, the posts of Chairman and Vice-Chairman were abolished and the government is now formally led by a President (currently Hu Jintao) and a Vice-President (currently Zeng Qinghong).

The dominance of the State Council means that the function of the NPC is largely superficial in that it ratifies State Council decisions rather than devises any policies of its own; in other words, notwithstanding a recent increase in its powers, the NPC was and remains little more than a rubber-stamp. This has done little to strengthen the legal rational legitimacy of the Chinese government. Despite the official rhetoric about the supremacy of the NPC in government decision making, all important government decisions are made behind closed doors by a handful of men. The annual plenary sessions of the NPC, which are heavily publicized throughout the country, are just for show. They are, in truth, an outward attempt to provide a veneer of procedural uniformity and demonstrate a commitment to a legal rational system of decision making.

The party structure

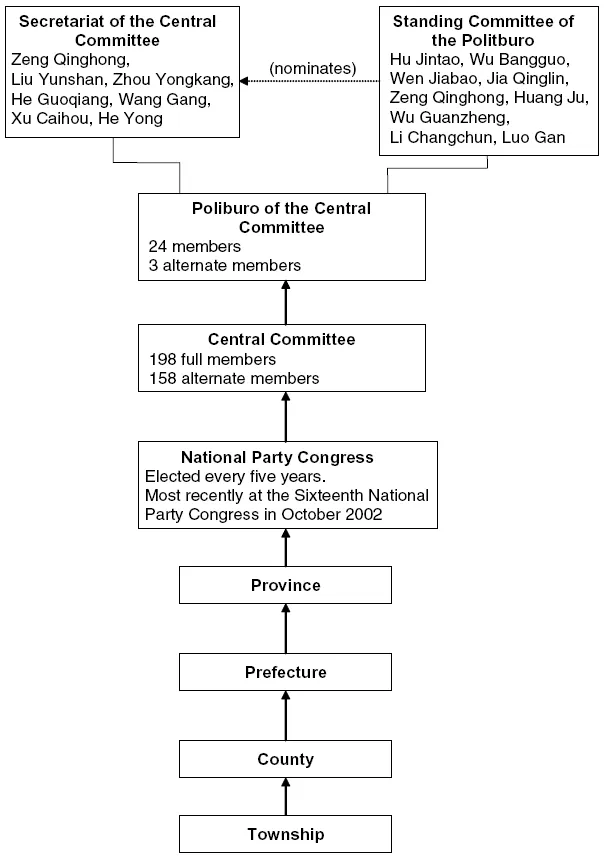

The party structure mirrors that of the government with a hierarchy of congresses from the township level up to the national level (Lieberthal 1995) (see Figure 2). The system of selection is also the same with delegates from each level elected by those members belonging to the congress immediately below with the exception of the township level where members are nominated by the next highest level up. In theory, the party is headed by the National Party Congress (not to be confused with the National People’s Congress) which comprises approximately 2,000 members and convenes once every five years for approximately one week. The National Party Congress (theoretically) acts as a forum for debate on important party matters, but in reality this function is carried out by its Central Committee which comprises about 350 full members (including alternate members) and holds five annual plenary sessions before being reconstituted.

As with the state, party policy is ultimately decided by a much smaller group of people in the form of the Politburo (about 20 members) and within that group the PSC which is made up of about six men. Like the State Council, the PSC is a secretive organization which meets in private to formulate party policy (usually at the seaside resort of Beidaihe, not far from Beijing). At the Eighth National Party Congress in 1956, the PSC was led by a Chairman and under him were five Vice-Chairmen and a General Secretary. The posts of Chairman and Vice-Chairman have since been abolished and the party is now led by a General Secretary (currently Hu Jintao) who is also head of the Secretariat, a body that was resurrected in 1982 to take care of routine party work.

Like the NPC, therefore, the National Party Congress and its Central Committee are primarily rubber-stamping bodies. Although the Central Committee enjoys certain formal powers such as the power to “elect” (i.e. approve) the composition of the Politburo and the PSC, and is a much more active debating chamber than it was during the Mao era, its principal purpose is to ratify draft documents that are handed down by the PSC. The National Party Congress is even more toothless than the Central Committee. As Saich (2001: 86) points out, in meeting once every five years its role is restricted to ‘providing a display of power and unity, and more important “milestones” in party’s history’. As with the state apparatus, this makes for a very weak legal rational system in China. One important point to remember about the institutions of party and state in China is that they are largely one and the same entity. As Zheng Shiping (1997) has shown, although official theorists maintain that the state is separate from the party, the party has always dominated the state by consistently staffing its key decision-making bodies with senior party personnel; in other words, those who have occupied leading positions within the State Council have usually occupied leading positions within the PSC. So, for example, in 1956 (after the Eighth National Party Congress) Mao was Chairman of both the party and the state, Zhu De was Vice-Chairman of the two institutions, Liu Shaoqi was Vice- Chairman of the party and Chairman of the NPC (effectively third-in-command of the state) and Zhou Enlai was a party Vice-Chairman and Premier. Consequently, all important government decisions were (and have continued to be) made by leading party members. There is no genuine separation of powers in Chinese politics.

Figure 2 Simplified structure of the Chinese Communist Party (2005).

The secretive and elitist nature of decision making in China and the domination of the party over the state has been matched over the years by the neglect of other legal rational procedures (Teufel-Dreyer 1996: 90–1). For example, on no occasion during the years 1956–77 did any National Party Congress see out its statutory five year term. Conversely, the Eighth Central Committee (constituted in 1956) served a 13 rather than a 5 year term. The reliability of government procedure is no better. During the 30 years from 1949 to 1979, the NPC did not convene for 13 of them, including one entire 8 year period from 1966 to 1974. Dismissals and appointments of senior office holders have also been arbitrary. As Chairman of the state, Liu Shaoqi’s term in office was scheduled to end in January 1969. However, he was deposed three months earlier and not by the NPC (the only body constitutionally empowered to do so), but by the Central Committee, a party organ (see Chapter 3). Similarly, the appointment of Hua Guofeng as Premier (a government post) in 1976 and the simultaneous removal of Deng Xiaoping as Deputy Premier were carried out by the Politburo during a party conference (see Chapter 4).

The military

Any discussion of China’s power structure would be incomplete without examining the integral role of the PLA, which includes a standing army, navy and air-force (Whitson and Wang Chen-hsia 1973). Although the military relinquished administrative control a few years after the revolution, it continued to participate in party-state affairs. This was born out of tradition. During the revolutionary years, the relationship between the party and the military (then known as the Red Army) was virtually impossible to differentiate. Non-military men often advised on tactics for guerrilla warfare whilst the military frequently implemented policy (e.g. land reform) in areas where the party was not well represented.

The military retained its administrative role in several ways. One way was through the transfer of military personnel into civilian jobs such as Deng Xiaoping who moved from Political Commissar of the Second Field Army to Vice-Premier (in 1954) and member of the PSC (in 1956). Inevitably, Deng and others like him did not simply sever their loyalty to the military on assuming their civilian positions. In fact, in many cases, they retained extremely close ties with former military colleagues from their old military units. According to Whitson (1969), Chinese politics during the early period (and beyond) was characterized by policy disputes between representatives from the different field armies of the old Red Army.

Some scholars have suggested that the transfer of military personnel into civilian administration posts was often made at the expense of “party-only” personnel. Mozingo (1983) suggests that whilst many party members did not play a leading role in actually fighting the revolution, they were far better qualified as technocrats to run the affairs of state. Mozingo concludes from this that if there had not been such a massive shift of personnel from military to party-state, the party would have found it much easier to control the military.

The link between military and party-state was also maintained through the appointment to civilian posts of people who kept their military positions. This was the case at all levels of the hierarchy all the way to the very top with several leading military officials appointed to powerful positions in the party and the government. Zhu De (Vice-Chairman of the party and the state) and Lin Biao (party Vice-Chairman and Vice-Premier) were high-ranking military officials, as were Peng Dehuai and Li Xiannian who both became full Politburo members and Vice-Premiers under the new political order. Perhaps most significantly, a new state post of Minister of Defence was set up and assigned to a serving military leader (the first incumbent was Peng Dehuai). Although formal control over the military lay with the Military Affairs Commission which was a party-run body (of which the Minister of Defence was a member), the Minister was given considerable autonomy on all the key areas of military affairs. In effect, the military was controlled by one of its own.

The blurring of the boundaries between the military and the civilian administration has given rise to the perennial problem of who controls who? According to a famous Mao dictum, “the party must always control the gun”. However, in allowing the military to play such a prominent role in civilian matters, the CCP has often found it difficult to adhere to this principle, as was particularly evident during the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution when the military functioned as de facto ruler following the collapse of the government (see Chapter 3). The military overlap into civilian affairs has also had a negative effect on legal rational proceedings in China. By allowing for such an incestuous relationship to exist between the party, the state and the military, it has often been hard to tell precisely which institution is making the decisions and whether they are constitutionally entitled to do so.

Ideology and legitimacy

A more definite form of regime legitimacy during the early period was ideology. As discussed in the introductory chapter, the official ideology of the PRC in 1949 was (and remains) Marxism, a doctrine which prioritizes the interests of the proletariat or working class through the leadership of the CCP. So what were the proletarian interests that the CCP sought to represent? In accordance with orthodox Marxism, CCP rhetoric focused on the necessity of eliminating the exploitation inherent in the capitalist system (the penultimate stage of human society). Under capitalism, it was argued, the ruling bourgeois class exploited the proletariat by forcing it to sell its means of production (i.e. its labour) for a pittance and often under oppressive working conditions. The new regime vowed to extinguish all vestiges of private ownership upon which such exploitation rested and build a society based on the socialist principles of equality and freedom in which the proletariat were not only equal in terms of their personal income, but also in terms of their wider opportunities in areas such as education, employment and even leisure. This was the utopia (i.e. communism) that the CCP claimed to be working towards; its ideological legitimacy depended on the extent to which the utopia was realized.

Chinese Marxism and Maoism

But much like Lenin and the Bolsheviks, Mao and the CCP reinterpreted Marxism. Despite adhering to the basic Marxist principle of overthrowing the bourgeoisie and liberating the proletariat, the CCP did not conceptualize these two classes within an urban based framework as Marx and Lenin had done (Shum Kui Kwong 1988: 6). Given that over 80 per cent of the Chinese population lived in the countryside, the party developed a more agrarian understanding of class so that the bourgeoisie was predominantly made up of the landlord class and the proletariat was predominantly made up of the ...