- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Metal Matrix Composites

About this book

The concept of reinforcing a material by the use of a fiber is not a new one. The Egyptian brick layer employed the same principle more than three thousand years ago when straw was incorporated into the bricks. More recent examples of fiber reinforced composites are steel-reinforced concrete, nylon and rayon cord reinforced tires, and fiberglass reinforced plastics. In the last several years considerable progress has been made on new composite structures particularly utilizing boron (on tungsten substrate) fibers in various matrices. Many of these advances have been reviewed recently by P. M. Sinclair1 and by Alexander, Shaver, and Withers.2 An excellent earlier survey is available by Rauch Sutton, and McCreight.3 Boron-reinforced epoxy composites are being fabricated and tested as jet engine components, fuselage components, and even as a complete aircraft wing because of the tremendous gain in experimentally demonstrated properties such as modulus, strength, and fatigue resistance, particularly on a weight normalized (e.g., strength/density) basis. Other than glass/epoxy and boron/ epoxy composites and perhaps boron/aluminum, the systems now under study are in the early stages of research and development. These include other boron/metal composites, graphite/polymer, graphite/metal, graphite/graphite, alumina/metal, and aligned eutectic (directionally, solidified) combinations. As Sinclair points out, designers are wary about filamentary composites becausethere is little background information and scant experience.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

The concept of reinforcing a material by the use of a fiber is not a new one. The Egyptian brick layer employed the same principle more than three thousand years ago when straw was incorporated into the bricks. More recent examples of fiber-reinforced composites are steel-reinforced concrete, nylon and rayon cord-reinforced tires, and fiberglass-reinforced plastics. In the last several years considerable progress has been made on new composite structures particularly utilizing boron (on tungsten substrate) fibers in various matrices. Many of these advances have been reviewed recently by P. M. Sinclair1 and Alexander, Shaver, and Withers.2 An excellent earlier survey is available by Rauch, Sutton, and McCreight.3 Boron-reinforced epoxy composites are being fabricated and tested as jet engine components, fuselage components, and even as a complete aircraft wing because of the tremendous gain in experimentally demonstrated properties such as modulus, strength, and fatigue resistance, particularly on a weight normalized (e.g., strength/density) basis. Other than glass/epoxy and boron/epoxy composites and perhaps boron/aluminum, the systems now under study are in the early stages of research and development. These include other boron/metal composites, graphite/polymer, graphite/metal, graphite/graphite, alumina/metal, and aligned eutectic (directionally solidified) combinations. As Sinclair points out, designers are wary about filamentary composites because “there is little background information and scant experience.”

The paucity of mechanical data, difficulties in fabrication, high costs, and degradation reactions at anticipated use temperatures have all contributed to the cautious development of reinforced metals. There is also a natural reluctance of the designer to undertake new design concept development. This is required since conventional concepts do not optimize the use of fiber composites. Competitive advantages that metal matrix composites offer over conventional metallic systems include the ability to: (1) take advantage of the anisotropic character of the composite in the efficient design and fabrication of structures, (2) tailor-make a material to meet a specific set of engineering strength or stiffness requirements, and (3) increase the stiffness, strength, and thermal stability of such common engineering alloys as aluminum, titanium, and nickel. It is not unusual to demonstrate weight savings to 40% on specified structures, often with significant increases in fatigue strength, stress rupture, and creep properties.

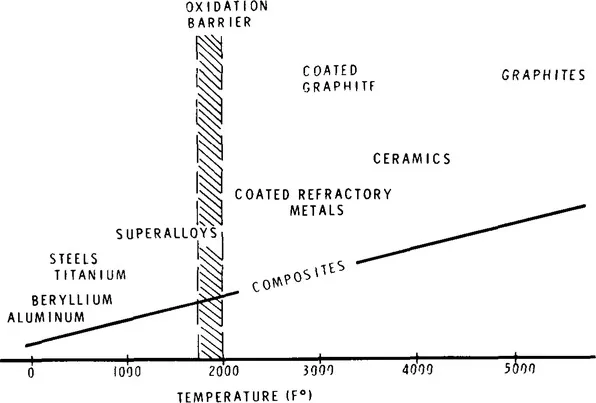

In comparison to other composite matrices, the most obvious potential advantage of the metal matrix is its resistance to severe environments, toughness, and retention of strength at high temperatures. Burte and Lynch4 have emphasized that the most unambiguous potential for future use is at temperatures above 1600° to 1800°F (871° to 982°C) when considering the competition from the more familiar directions of metallurgical development or polymer matrix composites. In a composite structure it is possible to emphasize environmental stability of the matrix at elevated temperatures since the required mechanical strength and stiffness can be obtained from the reinforcement. In homogeneous materials, mechanical properties and environmental stability may have to be compromised to produce a useful structure. In filamentary reinforced metals the shear strength requirements of the matrix are nominal since the matrix serves only to transfer load into the filaments. Figure l5 schematically illustrates the broad range of temperatures over which composite structures with various matrix materials may be considered. Up to about 1000°F (538°C), several potential metal composite systems have already been identified. For high temperatures, where oxidation presents a major problem in the development of ductile structural materials, stable reinforcements such as continuous alumina filaments have considerable potential. At temperatures below 600°F (315°C) the potential is less clear; but possible advantages of a metal matrix compared to a polymer matrix include improved abrasion and erosion resistance, greater shear, bearing, and transverse strengths, increased toughness, the ability to use conventional metal processes, and greater deformation prior to fracture. Disadvantages include higher density, more difficult fabrication, matrix-filament reactions, and higher cost. The metal matrix can provide a meaningful contribution to the strength and elastic modulus in all directions.

FIGURE 1. Temperature regimes of usefulness of various materials.

A body of important mechanical property data has been obtained within the last two years. This review concentrates on the recent literature, partly because this is where most of the information on limiting mechanisms and properties is found, and partly because much of the earlier work was conducted on inadequately characterized materials, sometimes poorly bonded or containing reinforcing filamentary materials with widely disparate mechanical properties. In many instances, as Tsai suggests,6 the unique character of filament-reinforced metals demands more sophisticated mechanical tests than have generally been applied. The anisotropic character of composite structures demands substantial emphasis on properties associated with multiaxial stress states as opposed to the early reliance on uniaxial tensile data to characterize these materials. With an increasing availability of a variety of high strength, high modulus continuous filaments, the number of potential filament/metal systems is rapidly increasing. Advances in fabrication techniques have produced composite structures with reproducible properties, the most advanced being boron/aluminum.

Emphasis in this review has been placed on systems where a considerable body of mechanical data has been obtained and can be critically examined. It is those systems which are closest to engineering development that the authors felt would be of most interest to the reader. Of necessity, several areas were not covered in much detail, for instance, graphite-reinforced metals, where less effort has been expended to date and the reader is referred to the cited references for further information. A separate section was included on whisker-reinforced metals as unique composite structures; but generally, these materials have not gained the prominence predicted for them ten years ago. Directionally solidified eutectics, which are sometimes considered a special case of whisker-reinforced structures, have also been considered separately. A section on mechanics has been included which suggests the available methods to predict mechanical properties of composite structures and the response to various external loads. It is mainly a compilation of referenced approaches since little has been done to apply more than a simple “rule of mixtures” analysis in most metal composites. It appears to the authors that this is an area where much could be accomplished.

Chapter 2

Reinforcements

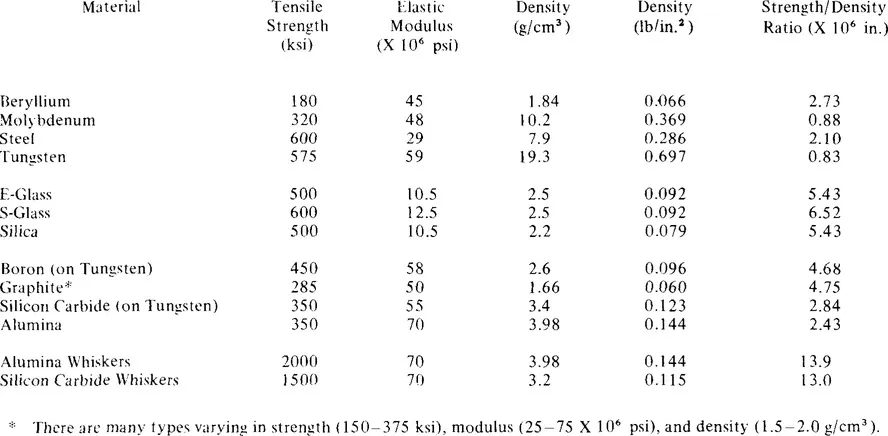

During a period of less than ten years a wide selection of high modulus, high strength, low density, and often refractory filamentary materials has become available as candidate reinforcements for metallic materials. A number of these are listed with typical mechanical properties in Table 1, with the more familiar glass and metal wire filaments given for comparison. For metals the filaments of major interest have been boron, silicon carbide, alumina, refractory wires, and graphite. In many cases the preparative methods result in problems such as defects and residual stresses, which mitigate against maximizing the mechanical properties of composite structures. A silicon-carbide coated boron with slightly lower tensile strength than boron (Borsic®) is also made and used where boron-metal interactions degrade the filament.

Boron filaments are produced by chemical vapor deposition of boron on a hot 0.5 mil tungsten wire substrate7 from boron trichloride and hydrogen at approximately 1000°C. The typical filament is 4 mils in diameter with strengths averaging 450 × 103 psi. A filamentary fatigue life in excess of a million cycles (using a tension-zero-tension cycle at 150 cycles/minute) has been measured using a cyclic load of half the mean tensile strength. The density of 2.6 g/cm3 is slightly greater than E-Glass, but the specific modulus of boron is far superior to that of glass fiber.8,9

TABLE 1

Filament Properties

Filament Properties

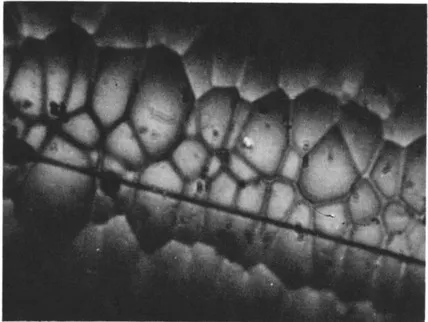

The boron deposit is extremely fine-grained, bordering on being amorphous.10 The surface typically has a “corn-cob” appearance (unless contaminated with oil or grease films which are sometimes found on “as received” filaments).11 During the deposition process the tungsten wire is at least partially converted to tungsten diboride12 and cooled rapidly from the hot zone in highspeed processing. Residual stresses are generated in the boron filaments from the differences in thermal expansion between the boron deposit and substrate. These residual stresses make the filaments susceptible to longitudinal cracking, as shown in Figure 2. Complete fiber-splitting in 1 -ft lengths of boron filaments was observed by Burte, Bonanno, and Herzog.11 This fiber-splitting is apparently responsible for low transverse strengths in unidirectional boron/aluminum conposites which will be examined in more detail in the mechanical property discussions.

FIGURE 2. Surface of boron filament with longitudinal crack (2000x).

Substrates other than tungsten have been examined to reduce the cost and also produce a boron filament having a density somewhat closer to that of boron (2.34 g/cm3). Fused silica is one example. Diborane has been decomposed at 700°C to form boron on silica, the lower temperature of deposition necessary for the substitution of the silica substrate for tungsten.8, 11 The silica-boron filament had strengths up to 350,000 psi and a density of 2.35 g/cm3, but the deposition process was difficult and it has not replaced tungsten-boron. To retard degradative reactions in metals, more inert materials such as silicon carbide14 and boron nitride15 have been applied in thicknesses of less than 1 mil.

Silicon carbide has been deposited directly on tungsten16 using ethyltrichlorosilane (CH3SiCl3), hydrogen, and argon at approximately 1300°C This is a difficult synthesis by vapor deposition and the filament properties have varied considerably. Silicon carbide has a higher density at 3.4 g/cm3 but the retention of strength at higher temperatures is very good. Recent strength values have exceeded 350,000 psi.

Single crystal alumina filaments have been produced from molten alumina utilizing a carefully controlled drawing process.17 The continuous filament is typically about 10 mils in diameter, with a strength of 350,000 psi and with high residual stresses as-grown. Voids within the crystals and morphological defects have been found which presently limit the filament strength. The strength has been found to be extremely sensitive to the presence of surface defects.18 The density is comparatively high at 3.98 g/cm3. These problems are offset, however, by the excellent high temperature properties of alumina and its stability in many transition metals of interest.

Considerable effort has been expended in recent years to produce high strength graphite fibers. Fiber synthesis usually involves pyrolysis and high temperature processing of polymeric precursor materials, such as polyacrylonitrile or rayon filaments which are graphitized at temperatures >2600°C.19 Graphite yarn is available which exhibits relatively high strengths and moduli. Densities range from 1.4...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Crc Uniscience Series

- Contents

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Reinforcements

- Chapter 3 Consolidation

- Chapter 4 Compatibility and Fabrication

- Chapter 5 Refractory Metal Wire Composites

- Chapter 6 Whisker Reinforced Metals

- Chapter 7 Tensile Properties

- Chapter 8 Compression

- Chapter 9 Fatigue

- Chapter 10 Impact

- Chapter 11 Elevated Temperature Tensile Strength

- Chapter 12 Creep and Stress Rupture

- Chapter 13 Eutectic Composites

- Chapter 14 Mechanics of Composites

- Chapter 15 Improved Mechanical Properties

- Chapter 16 Some Prospects for the Future

- Chapter 17 Conclusions

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Metal Matrix Composites by C.T. Lynch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.