![]()

1 | Elucidation of Vasopressin Signal Transduction Pathways in Vascular Smooth Muscle

Kenneth L. Byron and Lyubov I. Brueggemann |

CONTENTS

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Concentration-Dependence of AVP-Induced Ca2+ Responses in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Measured with Fura-2

1.3 Proximal Signaling Events Underlie Distinct Ca2+ Responses to Varying [AVP]

1.4 Elucidating Downstream Effectors of AVP-Stimulated Ca2+ Spiking

1.5 Ion Channel Targets in AVP Signal Transduction

1.6 A More Physiological Model System

1.7 Drilling Down to the Molecular Details of KV7 Channel Modulation

1.8 Clinical Pharmacology of KV7 Channels and Its Cardiovascular Consequences

1.9 Developing New Therapies for Diseases of Altered AVP Secretion

1.10 Methodological Considerations

1.11 Summary

References

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Arginine8-vasopressin (AVP), also known as antidiuretic hormone, is a peptide hormone that is synthesized by magnocellular neurons in the hypothalamus of the mammalian brain. AVP is stored in secretory vesicles within nerve terminals located in the posterior pituitary gland, from whence it can be released into the systemic circulation (Treschan and Peters 2006). One of vasopressin’s primary functions, as its name implies, is to constrict the vasculature to elevate blood pressure (BP). This important function comes into play when AVP is released from the pituitary nerve terminals following an increase in plasma osmolality or a fall in BP. Its primary endocrine signaling actions are two-fold: AVP exerts antidiuretic actions by stimulating the kidneys to increase water reabsorption, and it exerts vasoconstrictor actions by stimulating contraction of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Through this combination of actions, AVP plays an important part in restoring BP and water balance.

Plasma AVP exerts a potent antidiuretic effect on the kidney, with a maximal antidiuresis occurring, on average, at plasma [AVP] of approximately 4 pM (Baylis 1987). With a normal mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 70–105 mmHg and normal water balance (plasma osmolality approximately 280–285 mOsmol/kg), the concentrations of AVP in the systemic circulation are undetectable by conventional radioimmunoassay techniques (Baylis 1989). However, measurements conducted in human volunteers subjected to either increasing plasma osmolality or lowering of MAP revealed that either stimulus can increase circulating [AVP] in proportion to the magnitude of the stimulus (Baylis 1983). Increasing plasma osmolality from 280 to 310 mOsmol/kg increased [AVP] from undetectable levels to approximately 10 pM; by comparison, lowering BP was a more effective stimulus, elevating plasma [AVP] to as much as 500 pM when BP was lowered by 60% (Baylis 1983, Baylis and Ball 2000).

At the level of the vasculature, the BP restoring actions of circulating AVP have been attributed to the vasoconstrictor effects elicited by binding of AVP to V1a-vasopressin receptors on VSMCs, particularly those located on the surface of arterial smooth muscle cells of the splanchnic circulation. The splanchnic circulation supplies oxygen and nutrients to the gastrointestinal tract via a vast arterial network of resistance vessels originating from the celiac trunk, the inferior mesenteric artery and the superior mesenteric artery. Mesenteric arterioles have been found to be highly sensitive to AVP, constricting in response to concentrations of AVP as low as 10 pM (Altura 1975). Constriction of the splanchnic arterial vasculature can significantly increase total peripheral vascular resistance and thereby provides a very effective mechanism for restoration of BP.

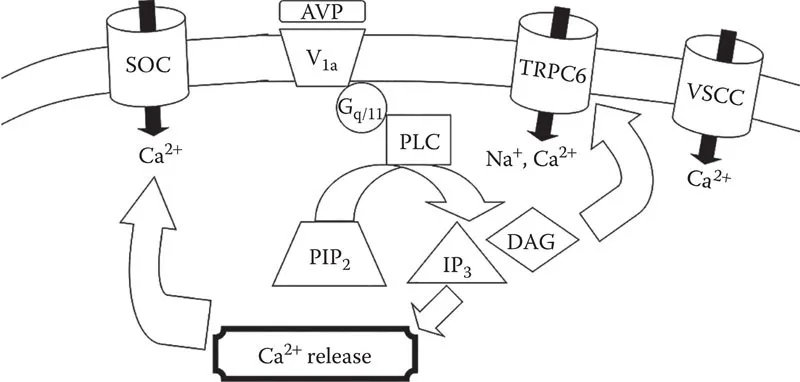

The signal transduction pathways whereby binding of AVP to V1a receptors results in contraction of VSMCs had been extensively studied by the early to mid-1990s. Because elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) was recognized as the primary effector of smooth muscle contraction, many studies measured changes in [Ca2+]cyt in response to AVP, in combination with various biochemical and pharmacological approaches to elucidate the signaling pathways that might elicit this response. The V1a receptor is in the family of G protein-coupled heptahelical receptors (Morel et al. 1992). It had been determined to be coupled to Gq/11 proteins (Wange et al. 1991, Thibonnier et al. 1993), which link agonist binding to activation of phospholipase C (PLC). PLC cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a minor membrane phospholipid, into two components: diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) (Berridge 1984). The latter compound was well established as an effector of the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Berridge 1984). In VSMCs, Ca2+ is stored within the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR); activation of Ca2+ channels on the membrane of the SR by IP3 results in release of the stored Ca2+ into the cytosol where it can activate the contractile proteins. Thus, this pathway provides a reasonable mechanism to explain how AVP increases [Ca2+]cyt to elicit smooth muscle contraction. Evidence supporting this signaling pathway included the demonstration of robust increases in [Ca2+]cyt in VSMCs in response to AVP even in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Vallotton et al. 1986, Byron and Taylor 1995), corresponding to measurements of AVP-induced IP3 formation (Doyle and Ruegg 1985, Aiyar et al. 1986). In addition to the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores, AVP was also shown to increase influx of Ca2+ across the plasma membrane, an effect that was largely attributed to activation of store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) channels (Byron and Taylor 1995) and/or non-selective cation channels, including TRPC6 (Soboloff et al. 2005, Maruyama et al. 2006), which can be activated by DAG. A hypothetical signaling pathway for AVP-induced elevation of [Ca2+]cyt and VSMC contraction was developed to account for all of these observations (Figure 1.1). Although it was generally well accepted, there was at least one crucial discrepancy that raised questions about its validity.

What had often been overlooked or ignored in considering the vascular AVP signal transduction model is the concentration-dependence of the components. Although AVP robustly elevates [Ca2+]cyt in VSMCs by releasing intracellular Ca2+ stores, this effect is half-maximal at approximately 5 nM AVP, in good agreement with measurements of AVP-stimulated IP3 formation, which similarly requires nanomolar concentrations for half-maximal activation (Doyle and Ruegg 1985, Aiyar et al. 1986, Ito et al. 1993). Activation of SOC entry and TRPC6 currents were also reported based on exposure of VSMCs to 50–100 nM AVP (Byron and Taylor 1995, Soboloff et al. 2005, Brueggemann et al. 2006). It appears that the hypothetical Ca2+ signaling model (Figure 1.1) requires nanomolar concentrations of AVP even though such concentrations are at least an order of magnitude higher than the highest concentrations measured in the systemic circulation. Can this model really explain the vasoconstrictor actions of AVP observed at physiological concentrations of AVP in the 10–100 pM range? We have explored this question for more than two decades and will describe some of our approaches and their remarkable outcomes in the remainder of this chapter.

FIGURE 1.1 Hypothetical AVP Ca2+ signaling in VSMCs. Binding of Arg8-vasopressin (AVP) to the V1a vasopressin receptor is coupled to activation of the Gq/11 G protein α-subunit, which in turn activates phospholipase C (PLC). PLC cleaves PIP2 to produce DAG and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). The latter activates a Ca2+ release channel in the SR, and the resulting depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores triggers activation of SOC channels on the plasma membrane. DAG can activate TRPC6 non-selective cation channels in the plasma membrane. Influx of cations can depolarize the membrane to activate VSCCs to further stimulate Ca2+ influx.

1.2 CONCENTRATION-DEPENDENCE OF AVP-INDUCED Ca2+ RESPONSES IN VASCULAR SMOOTH MUSCLE CELLS MEASURED WITH FURA-2

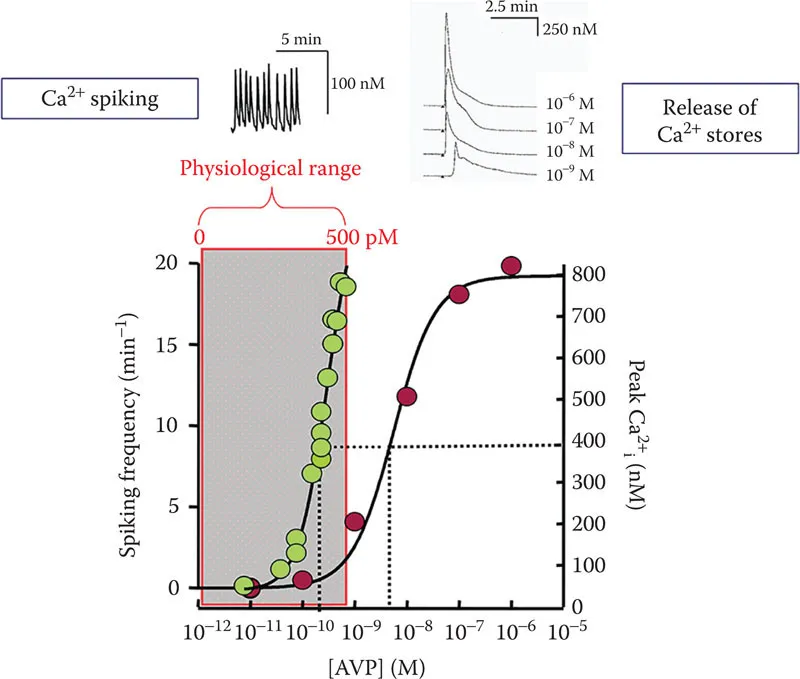

In our initial attempt to investigate the concentration-dependence of AVP-stimulated Ca2+ responses in VSMCs, the A7r5 embryonic rat aorta smooth muscle cell line was employed. A7r5 cells had already been reported to respond robustly to AVP and to stably express many differentiated smooth muscle characteristics (Kimes and Brandt 1976); in contrast, smooth muscle-specific markers, V1a receptor expression, and responses to AVP are often lost in primary cell cultures of VSMC (Thibonnier 1992, Owens 1995). We used the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura-2 to monitor [Ca2+]cyt in single A7r5 cells or in confluent monolayers of A7r5 cells exposed to increasing concentrations of AVP. In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, AVP stimulated a release of intracellular Ca2+ stores at supraphysiological concentrations, with an EC50 of approximately 5–10 nM AVP. In single cells, these responses were characterized by an abrupt rise in [Ca2+]cyt after a variable latency (decreasing latency with increasing [AVP]), reaching a maximal peak of 862 ± 43 nM Ca2+ at 1 µM AVP (Figure 1.2). Neither the magnitude of the AVP-stimulated Ca2+ release signal nor its concentration-dependence was appreciably altered by inclusion of nimodipine, a blocker of L-type voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels (VSCCs) (Byron 1996).

FIGURE 1.2 Ca2+ responses to varying [AVP] in A7r5 cells. Red symbols represent amplitude of Ca2+ release responses (scale bar on right). Green symbols represent frequency of Ca2+ spiking (scale bar on left). Representative examples of Ca2+ spiking and Ca2+ release time courses are shown above the graph. (Adapted from Byron, K. L., Circ. Res., 78, 813–820, 1996.)

When the same A7r5 cells were exposed to much lower concentrations of AVP, starting at 10 pM (10−11 M) and increasing in 10 pM increments, it was immediately apparent that a different Ca2+ signal was elicited. Spontaneous Ca2+ transients (rapid elevation of [Ca2+]cyt from a baseline of around 50 nM to a peak around 150–200 nM Ca2+, referred to as Ca2+ spikes) occurred at very low frequency (~0.02/min) in the absence of AVP. When [AVP] was increased to a threshold between 10 and 30 pM, however, there was an abrupt increase in spike frequency and the frequency continued to increase in a steeply concentration-dependent manner up to a maximum of ~17/min at 500 pM AVP (EC50 ~ 150 pM) (Byron 1996).

Despite their strikingly divergent sensitivities to AVP, both the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores and the Ca2+ spiking responses were blocked by a V1a-vasopressin receptor antagonist, suggesting that both effects are downstream of AVP binding to a single receptor subtype. However, several differences were noted in the Ca2+ spiking response compared with the Ca2+ release response: (1) Ca2+ spiking required extracellular Ca2+ and was abolished by nimodipine, whereas AVP-stimulated Ca2+ release occurred in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and was unaffected by nimodipine; (2) the Ca2+ spiking response to AVP was a frequency-modulated (FM) response (spike frequency changed dramatically while the amplitude of the Ca2+ spiking was fairly constant over a wide range of AVP concentrations); in contrast, the release of intracellular Ca2+ by AVP was an amplitude-modulated (AM) response (increasing amplitude with increasing [AVP]); and (3) Ca2+ spiking occurred nearly synchronously among all of the cells of a confluent monolayer, whereas Ca2+ release responses occurred asynchronously, even among neighboring cells (Byron 1996). These exciting new observations suggested that distinct Ca2+ signaling mechanisms might underlie the moment-to-moment regulation of vascular tone by picomolar concentrations of AVP. Although the signaling pathway for AVP-stimulated release of Ca2+ stores was already described, it remained to be determined what mechanisms produce the Ca2+ spiking respo...