![]()

Part I

Cities and the fabric of encounter

![]()

1

Restricting contact

Segregation is a conspicuous phenomenon in our social and urban experience. It can be felt when we use a city’s spaces and seems ever present. It manifests in different cultures and regions, and is shown to be as ancient as the city itself. Segregation even seems to shape the city or at least to impregnate many of its localities (as seen in Charles Booth’s 1898 map of social classes in London above and in Plate 1).1 Social networks theorist Linton C. Freeman formulates one of the simplest and most powerful definitions of segregation: ‘restrictions on some form of social contact between persons who possess different socially relevant characteristics.’2 Segregation is a form of restricting interaction – a restriction that operates through differences. One intriguing and difficult aspect of segregation is that we carry with us the signals of the idiosyncrasies that define our identities – the very signals that differentiate us and by which we are recognised – which cannot simply be rejected or ignored. If we think of segregation as a form of restricting contact, we can perceive that it involves the body and is enacted in the presence or absence of the body as a key aspect of the materiality of social relations. Whether we agree with this initial definition, we must admit that the problem of segregation is pervasive and continues very much alive. Though elusive, it becomes visible in the cars burnt in Paris, the distinct buses used by immigrants in Foggia and the different areas for different social classes in Rio de Janeiro.

Space is usually seen as both the materialisation and the medium of segregation. Spatial segregation is a way of engendering social distance. Through choice or a lack of choice, groups sharing race, class, income levels or lifestyles live close to each other. We see spatial segregation as a form of social distance. Space separates.

However people hardly remain static in segregated territories. They move through different areas and in different situations in the city, commuting to work and socialising in different places. Socially different people may pass through and share the same places. They may be side-by-side in the subway or on the street. We could even think that this mobility would render space an obsolete form of segregation. But if that is the case, why do we still observe segregation as an active part of life in our cities? If we are so mobile, why is the ‘other’ still mostly unknown to us? Cities still seem to be efficient systems for inducing distance between the different.

Nonetheless, I suggest that a response for the key question on how we experience social segregation in contemporary cities still implies an active role for urban space – a role that, however, cannot be contained in territorial segregation. The core of my argument is that, given that our societies are, among other things, systems of encounter involving high levels of mobility and complexity, we must examine space beyond the usual visions of spatial segregation. By providing a critique of the ways in which we assume space as an explanation for social distance, this chapter prepares the grounds for a reinvigorated study of the problem – an approach intended to introduce the relations formed by our encounters as possibilities for recognising the other. Placing the emphasis on routines and co-presence as aspects of social integration, on the differences in forms of social life and on active capacities in the formation of personal social networks, this chapter proposes a form of encompassing our daily actions and movements that considers the spatialities of co-presence and encounter, and of absence and non-encounter, as constitutive elements of segregation.

This intention implies entering an endless interweaving of movement and encounters in cities. The approach adopted here makes a somewhat eclectic use of ideas ranging from Freeman’s view of segregation as restrictions on contact to Anthony Giddens’s emphasis on the encounter as an element of social integration. It thereby looks to explore the actions and mobilities of urban actors shaping the integrative or segregative potential of the encounter in a city. This marks a shift in focus away from the relatively stable segregation of places – where separation is assumed rather than shown in its social manifestation – and towards the role of space and the body in the mediation of contacts between different actors. I wish to understand social segregation in a more dynamic form by considering how it is enacted in the trajectories of people in urban space. This approach is developed as a way of comprehending the forms through which the other is rendered invisible in our routines – a way of verifying how social distance becomes established in daily life, social differences become structural distance and the other an unknown form of otherness.3

This reformulation of the spatiality of segregation locates the body – both the medium and the sign of identities and differences – and its actions as the instances where segregation is socially revealed and lived. In other words, in contrast to a literature traditionally focused on territorial dimensions, I intend to locate the trajectories of the body as central to the spatiality of segregation. My aim is to show how the urban circumstances of the encounter generate possibilities for interaction and the emergence of different social networks within the same city, at times configuring distinct social worlds in which the other remains unknown. In so doing I hope to show that space still plays a key role in segregation, in fact deeper than the usual approaches allow us to see – a role that can help us achieve a more comprehensive understanding of our constant experience of segregation: a subtle process of social distancing that ultimately operates on and through the trajectories of the body.

A brief genealogy of a spatial reductionism: segregation as social division of space

[S]ocial relations are so frequently and so inevitably corrupted with spatial relations; … physical distances, so frequently are, or seem to be, the indexes of social distances.

Robert Park (1915:117)

This extraordinary phrase from Park, one of the leading theorists of the Chicago School in the first decades of the twentieth century, synthesises a socio-spatial view that still seems to pervade our understanding today: the understanding of the social and spatial relations (and distances) as though the social were not only expressed directly in the spatial, and vice-versa, but also explained sufficiently the way in which the other domain is defined. Segregation is an exemplary case of the conflation of social and spatial relations: a form of social control apparently definable by its pure spatiality. In fact this conflation seems to be assumed with such intensity that territorial segregation has became a surrogate for any form of social segregation, and the spatiality of segregated areas becomes a sufficient condition to explain low levels of interaction between the socially different. Traces of this vision of segregation, linked to places more than people’s behaviour per se, can be identified in the detailed work of Charles Booth on patterns of income, class and residential distribution in London, in 1889 and 1898 (see Plate 1).

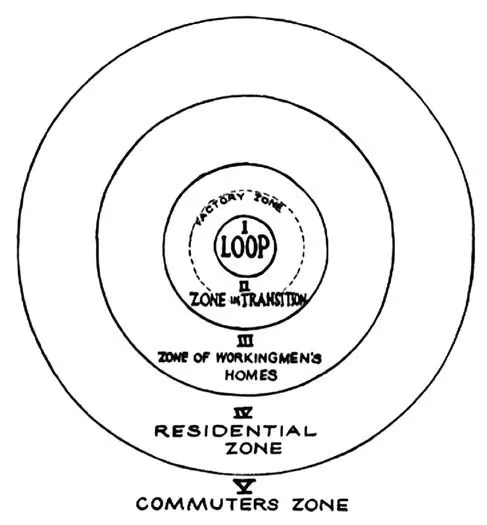

This inherently spatial view of segregation found theoretical support in the Chicago School, most specifically in Park’s works on spatial relations as an adequate replacement for the study of social relations and in E.W. Burgess’s seminal study of residential segregation in American cities (Figure 1.1).4 Indeed Burgess’s zone model of social patterning intrinsic to urban growth has been widely influential. The aggregation of socially similar actors – sharing similar levels of income and power – is indeed largely inherent to the process of spatial production and in the residential localisation mediated by land values. Through a circular process generated by economic dynamics, social groups differentiated in terms of income, cooperate productively at the same time as they compete for the best positions and advantages in urban space.5 The result is a pattern of location in specific areas of habitation that are locally homogenous and distinct from each other – a city where actors, as a whole, live in a dissociated form. It would be possible, therefore, to generate ‘maps of social segregation’ through the observation of urban morphology and the localisation of these areas.

Many lines of work stemmed from this view in the following decades, such as Duncan and Duncan’s dissimilarity index, Liberson on ethnical assimilation, Tauber and Tauber on black migration, Guest and Weed on causal relations in social and residential segregation, Massey and Denton on spatial patterns of racial segregation, and Quillian on black-white residential segregation and migration, among many others.6 Thomas C. Schelling famously showed how the effects of individual preferences on location unfold into patterns of residential segregation (see Plate 2), and how an integrated society would generally subside into a segregated one even though no individual actor strictly prefers this.7

Extensive empirical work reinforced the conflation. Farley found that residential segregation for ethno-racial motives was much higher in American cities than segregation by social class, a pattern independent of variations in education, occupation or income.8 The emphasis on space as a sufficiently accurate measure to understand the implications of social segregation is closely related to residential segregation.9 The dynamics of territorial segregation as a product and means of engendering social segregation certainly remains an area of great academic interest.10

Figure 1.1 Burgess and his model of urban zones naturalise segregation

A fixation on territorial segregation related to systems of identity11 might be traced back to the origins of the concept: a persistent ethno-racial segregation in American cities and elsewhere since the time of Burgess and Park.12 We should also consider the latent epistemology of such approaches: a view of socio-spatial relations from the standpoint of long periods of production rather than the fast pace of social reproduction, and a focus on visible, almost static spatial features rather than the elusive condition of contact between actors. Thus, the temporality of segregation in most approaches is the temporality of the production of space. Its spatiality is that of segregated areas. Segregation is usually seen as a form of geographically manifest social differentiation, resulting in weak interaction between groups, with space taken as a substitute for social dissimilarity and distance. This view might have over-shadowed other dimensions of segregation and deeper roles of space as highlighted in an interesting French debate stemming from Chamboredon and Lemaire’s work in the 1970s.13

These studies seek to challenge the racial origins of the concept of segregation, the residential outlook, fixation on instances of social production and the hypothesis of correspondence between social distance and spatial distance. More recently, some innovative approaches have focused on the segregation of individuals in social spheres and routinised activities.14 For instance, Schnell and Yoav’s work explores an index that emphasises an individual agent’s experience of isolation from or exposure to the actual everyday life spaces of other groups. Key points of these views are shared here. However, most of these approaches still tend to be centred on an understanding of actors as either dispersed or aggregated entities, assuming proximity of location as opportunities for encounter.

Such substantive views to segregation seem also dependent on a latent epistemology: the understanding of social and spatial relations immersed in the long temporalities of production instead of reproduction. The difference between these temporalities is enormous: the first encompasses the historical processes that constitute social and spatial formations, while the second emphasises the events as they appear in the present as the outcome of these processes, recursively replicating them and sometimes leading to change and new formations. The epistemological tendency to objectivise long-term processes has its own implications. First, concepts are generated in a way more in...