![]()

1

Yemen and the Yemenis: An Introduction

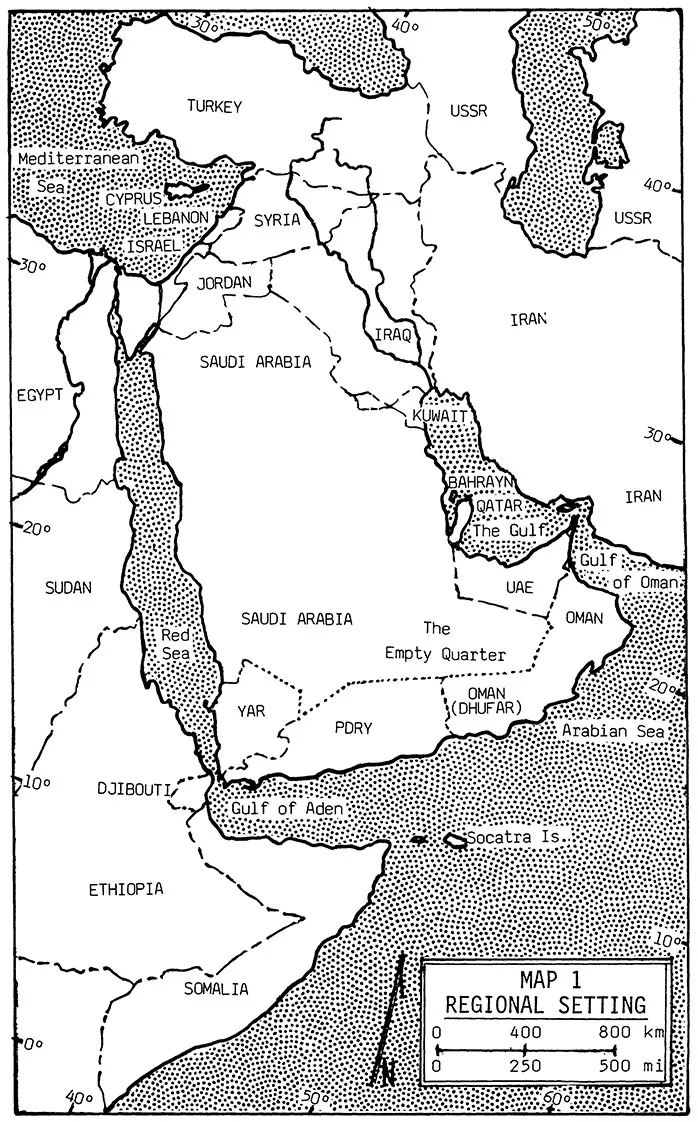

North Yemen, or, more properly, the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR), is located on the margins of the Arab world, on the southwest corner of the Arabian Peninsula, the corner that is formed by the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, pointed toward Ethiopia and Djibouti, and separated from the African continent by the narrow Bab al-Mandab Straits. (See Map 1.) It shares this corner of Arabia with South Yemen, the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), which is less to its south than to its southeast and east. The YAR is bounded unambiguously on the west by the waters of the Red Sea and less precisely on the north and northeast by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The YAR's long eastern border with the PDRY and its shorter northeastern one with Saudi Arabia are still undemarcated; the YAR and its two neighbors converge at an uncertain point on the edge of the inhospitable desert known as the al-Rub al-Khali, the Empty Quarter. Dwarfed by Saudi Arabia, which is eleven times its size, the YAR occupies a tiny portion of the land mass of the Arabian Peninsula. Although its exact size is made uncertain by undemarcated borders, it is roughly the size of the state of Nebraska or South Dakota. In this small area reside, according to the 1986 census, approximately nine million people, a bit fewer than in Ohio but more than in Michigan. The YAR's population is larger than that of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and slightly more than half the total for the entire peninsula. Its number of people may be four times that of the PDRY, even though the YAR has less than two-thirds the area of this neighbor. Together, the two Yemens contain a clear majority of the total population of the Arabian Peninsula.

Terrain and Climate

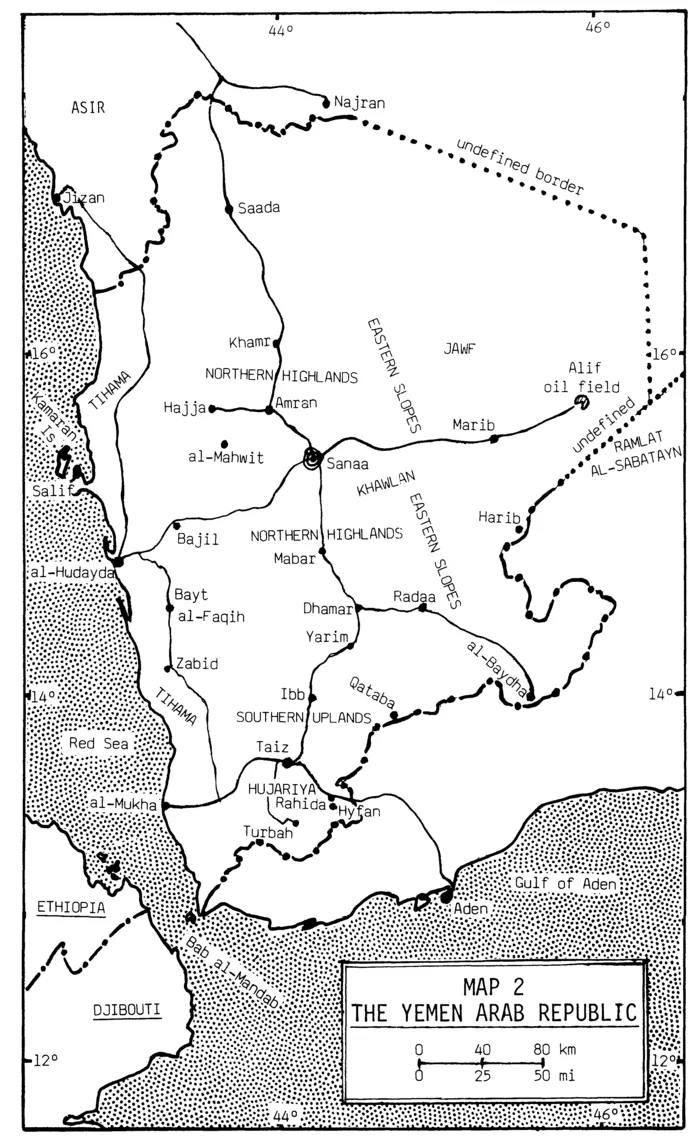

Much of North Yemen consists of ruggedly mountainous terrain, belying notions that the Arabian Peninsula consists of only flat or gently rolling expanses of sand desert and otherwise arid land. The steep, jagged mountains run roughly north and south the full length of the country, parallel to the Red Sea coast. (See Map 2.) The mountain peaks rise higher as one moves

south from the border with Saudi Arabia and attain their greatest height west of Sanaa, the YAR's capital city. The summit of Jabal Nabi Shuayb, at more than 12,000 feet (3,700 meters), is the highest point on the Arabian Peninsula. Though still formidable, the mountains gradually diminish in height as one moves south from Sanaa toward the PDRY. They turn nearly 90† to the east near the border between the two Yemens, and their southern face drops off precipitously several thousand feet to lowlands that then slope south toward Aden, the capital of the PDRY, and the Gulf of Aden.

North Yemen is located between the equator and the Tropic of Cancer, at about the same latitude as the northern half of Central America from Nicaragua to southern Mexico. Proximity to the equator means that the length of days and nights varies little from season to season and that periods of light and dark are roughly of equal length throughout the year. This, in combination with high elevations, results in a climate for much of the country that is pleasantly temperate year-round. Sanaa, at about 7,500 feet (2,300 meters [m]) and 15° North, boasts fine weather marred only by lip-cracking dryness and dust-laden winds during part of the year. A key to the pleasant weather of Sanaa and most of those areas of the country at altitudes from 4,500 to 9,000 feet (1,400 to 2,800 m) is the speed with which the earth's surface heats and cools in the often cloudless sky and thin atmosphere. Summer days, typically very warm and sometimes quite hot, are usually tempered by cool evenings and nights. Midwinter nights can be quite cold, and temperatures occasionally drop a bit below freezing during the early morning hours. Winter days, however, are generally warm, owing to the sunny, clear skies that usually prevail. The weather at low elevations, on the Red Sea coast and in the interior to the east and northeast, is far less benign.

Although more abundant in North Yemen than elsewhere on the Arabian Peninsula, the rainfall in most of the country is sparse and erratic at best. The country is on the edge of the Indian Ocean monsoon system. In years when the warm, moist winds from the southwest blow strong, the rain falls as the cooling air is forced up and over the mountains; but when the winds fail, the rain does not come and the land is subject to drought, sometimes for two or more years in succession. Ordinarily there are two rainy seasons, one in the spring and the bigger, more reliable one in the summer and early fall. Hailstorms occur in summer, but few Yemenis have ever seen snow, even from a distance. The rainfall in the Sanaa region, the geographic center of the country, ranges from 8 to 20 inches (20 to 50 centimeters) per year. Greater at the higher elevations to the west and in the uplands south of Sanaa, which are positioned to benefit first and most from the moist winds, the rainfall drops off markedly to the north, northeast, and east of Sanaa. By the time the winds reach these areas, if they reach them at all, they have been stripped of moisture.

The mountain spine of North Yemen helps divide it into four major geographic regions. The heart of the country is in and just to the east of this spine and is divided nearly 85 miles (135 kilometers [km]) south of Sanaa by the major north-south pass, the Samarra Pass, into two regions, the northern highlands and the southern uplands. The less extensive southern uplands, also known as Lower Yemen, are somewhat lower in elevation and less rugged than the much larger northern highlands, or Upper Yemen. A disproportionately large part of the population of North Yemen is concentrated on the plateaus and terraced hillsides as well as in the valleys and stream beds of the northern highlands and especially the southern uplands. It is in these two regions of higher elevation and cooler temperatures that most of the country's small amount of rain falls, making possible the cultivation of life-sustaining crops of sorghum and some wheat, barley, and alfalfa. Also grown here are coffee and qat, the privet-like shrub whose tender leaves are chewed regularly by many Yemeni men and women for their mildly stimulative effect. The rain and the wild vegetation and cultivated crops in streambeds and on the fine system of dry-well terraces of these regions provide sharp contrast to the forbidding aridity of most of the rest of the Arabian Peninsula, earning Yemen in ancient times the name Arabia Felix. Ibb province, in the southern uplands just below the Samarra Pass, is called the Green Province and, along with Taiz province farther to the south, supports the most intensive cultivation and the highest population density in the country. The climatic change is sudden and pronounced travelling south from Samarra-warmer, moister air as well as more abundant and different vegetation, including cacti and yuccas that do not thrive in the harsher, more austere climate in the northern highlands.

The Tihama, or coastal plain, is the third and the most clearly defined region of North Yemen. Varying in width from 20 to 40 miles (32 to 64 km), the Tihama runs the full length of the country, squeezed between the Red Sea and the mountains that rise abruptly to the east. Near sea level and very flat, the Tihama receives no appreciable rainfall and is extremely hot, hazy, and humid much of the year. The heat and humidity, especially during the summer sandstorms, are enervating and make work, and even living, difficult. At present, the Red Sea provides a livelihood for some fishermen, and its beaches and breezes afford relief and pleasure for a small number of others, mostly foreigners. Although most of it is extremely arid, and some of it is sand desert, the Tihama is cut east-west by several major stream beds, or wadis, each fed by the runoff from large catchment areas that begin high in the mountains to the east. Filled with water for only short periods during and after the rainy seasons, these wadis contain considerable amounts of water below the surface that bubble up at springs or can be tapped by shallow wells. Even the ports, fishing villages, and palm groves on the edge of the sea are sustained by the water that flows underground after falling as rain far inland on the mountains. The relatively small population of the Tihama is densely concentrated in places where this groundwater is readily accessible—at the base of the foothills and along the major wadis and their tributaries. In those few places where water is available in abundance, the Tihama is lush and tropical, dotted with irrigated fields of cotton, millet, bananas, papayas, melons, and vegetables. Indeed, modem technology and the sizable aquifer at the foot of the mountains make the wadis on the Tihama places of significant agricultural potential, more so than anywhere else in the YAR.

The fourth geographic region lies to the east and northeast of the peaks and plateaus of the northern highlands. In contrast to the sharp drop down to the Tihama, the mountains gently slope eastward toward the interior of the Arabian Peninsula and the forbidding Empty Quarter. The farther one moves east, the more the land looks like either a moonscape or a Hollywood desert. This large region is by far the most sparsely populated in all of North Yemen and contains no town of any size or consequence. The only bedouins in the country are found on the region's eastern edge, living a nomadic or semi-nomadic existence. Nevertheless, the runoff eastward for many miles from the mountains provides abundant groundwater to some places—for example, in Wadi Jawf and around the town of Marib. Modem pumps and irrigation works, the latter epitomized by the recent construction of a new version of the fabled Marib Dam, the engineering marvel of the Sabean Kingdom more than two millennia ago, hold out the promise of agricultural development in parts of the region. And more than agricultural change is in the offing. It is here that oil was discovered in 1984, and the new refinery and oil wells will surely rival the Marib Dam as symbols of the YAR's progress.

Settlements and Communications

Historic Yemen was, and today's YAR to a surprising degree still is, a country of a few small cities, many towns, and a vast number of small villages and tiny hamlets. The combined population of the YAR's three cities—Sanaa, with about 425,000 persons, and the much smaller Taiz (175,000) and al-Hudayda (250,000)—still comprise less than 10 percent of the total population of the country. By comparison, greater Beirut alone contained a third of the entire population of Lebanon in 1975. North Yemen's thousands of towns, villages, and hamlets are widely distributed over much of the country. Rooted firmly in the distant past, this settlement pattern persists today both because Yemen is still in the early stages of development and because the recent flow of workers from the countryside has been abroad rather than to the cities within the country. As a consequence, the YAR has thus far been largely spared the urban problems that have plagued most late-developing countries. On the other side of the ledger, the difficulty of delivering services and the inability of the state to exercise much control over the citizenry have been costs of the widely dispersed population. A land of rugged terrain in which settlement areas were linked, if at all, by tenuous and limited means of transportation and communications, North Yemen was and still remains marked by areas of isolation and great diversity from place to place, a sharp contrast to societies on deltas and in river valleys where populations are more homogeneous and accessible.

The vital center of North Yemen in recent decades has been the misnamed, misshapen "triangle," the area traced by the three roads that connect Sanaa, Taiz, and al-Hudayda. Each side of this triangle is roughly 150 miles (250 km) long, and the area enclosed is the southwestern third of the country. The state in modern times has rarely had effective control over more than the area of the triangle, and often the reach of the government has fallen well short of that. Much of what little modernization has come to North Yemen has taken place on and near the three roads that trace the triangle. In addition to the cities of Sanaa, Taiz, and al-Hudayda, four of the country's five largest towns—Ibb, Dhamar, Zabid, and Bayt al-Faqi—lie on these roads. Only Saada, far to the north, falls well outside the triangle.

The history of the YAR since 1962 is largely the history of its new roads as agents of integration and change. The asphalted, two-lane roads connecting the three cities, which roughly follow centuries-old footpaths and caravan ways, are the YAR's three main roads. The construction and paving of these modern roads was begun about 1960 and not finished until well into the mid-1970s. Spreading from this core, paved roads have been completed since the late 1970s from Sanaa to Saada in the far north, south from Taiz to Turbah, east from Sanaa to Marib, east from Dhamar to Radaa and al-Baydha, west from Sanaa to Hajja via Amran, north from al-Hudayda to the Saudi border and southeast from Taiz to the PDRY border. When completed, a second road between Sanaa and al-Hudayda, arcing south of the one built in the early 1960s, will ease traffic on the YAR's most heavily travelled artery. As significant as the paved roads has been the rapid construction of thousands of miles of dirt and stone feeder roads, making thousands of villages and hamlets reachable by four-wheel drive vehicles for the first time. Roadheads, advancing slowly behind bulldozers and blasting crews toward remote villages, are foci of change and sites of makeshift shops with imported canned goods, taxis to carry people to the cities, and drums of gasoline to fuel electrical generators and four-wheel drive vehicles. The new feeder roads mean new opportunities, and many Yemenis with money earned working abroad have been quick to buy the vehicles that will help them take advantage of these new opportunities.

People and Society

The peoples indigenous to the northern highlands, the southern uplands, and the eastern slopes are racially Arab Semites. They are small-boned and of diminutive stature—indeed, they are among the smallest people of the world. The people of the southern uplands, and of the PDRY to the south, tend to have slightly darker complexions and rounder facial features than those of the north and east, suggesting a greater mixing of the Semites of Arabia with other racial groups. The people of the Tihama, very different from those of the other regions, evidence strong influence of nearby Africa. Here are found the stature, color, and facial features of both Ethiopians and negroidal Africans.

Many persons familiar with both North Yemen and Afghanistan maintain that each of these late-developing countries is more like the other than like any other country in the world. The resemblance is as much or more a matter of culture and social organization than of geography and settlement pattern. North Yemen, like Afghanistan, is a pervasively Islamic country. Except for a small Ismaili Muslim population and a tiny Jewish community, both of which are now much smaller than in past generations, the people of North Yemen are divided between two Islamic groups, the Zaydis and the Shafais, and this sectarian division has had a profound effect, political and otherwise, on historic and modem Yemen. The two communities established themselves in Yemen early in the Islamic era, at least a thousand years ago, and have been the dominant groups in most generations since that time. The old myth of numerical parity notwithstanding, the Shafai community is and probably has been for a long time considerably larger than the Zaydi community. Over the centuries, the Zaydis came to reside in the mountainous highlands as well as in the far north and northeast, whereas the Shafais populated the southern uplands and the Tihama. The rough dividing line between the two communities is the same Samarra Pass that separates Upper Yemen from Lower Yemen, and the Iryan, an area to the west of Samarra, has been described as part of the DMZ—the demilitarized zone—separating the Zaydis and the Shafais. Ibb and Taiz provinces as well as al-Hudayda province are Shafai areas, whereas Dhamar province and the provinces to its north are Zaydi. South Yemen, the PDRY, is wholly Shafai.

Although the Zaydis are Shii Muslims and the Shafais are Sunni, the Zaydi branch of Shiism is more similar to the rationalist schools of Sunnism than to the mystical, millenarian sects that are typical of Shiism. Like Sunnism generally, Zaydi Shiism is an establishment religion, not one born of defeat and dissent. As a result, the very real differences between the two communities in Yemen have been and are less religious—less matters of dogma and ritual—than cultural, social, and political. The Zaydis of the northern highlands and the Shafais of the southern uplands constitute separate subcultures, the main features of which were forged in the history of the past four or five centuries. Each community has viewed its relationship to the other in "us-them" terms. Segregated socially as well as geographically, the members of each community have tended to feel more comfortable with and more easily understood by their own kind.

The differences between the Zaydis and the Shafais are partly matters of oppressors and oppressed, of warrior-rulers and subject peasants and merchants. The Zaydis have ruled the Shafais more often than not over recent centuries, and Zaydi jurists and theologians developed an elaborate political theory that justified the rule of the Zaydi ruler, the imam, over fellow Zaydis as well as non-Zaydi subjects. Almost all the imams' counselors, judges, and administrators were drawn from the upper ranks of the Zaydi community, and it was the Zaydi tribes in the north that supported the Zaydi imams with their armed tribal irregulars. The Zaydi imamate patronized culture, learning, and the arts, albeit to a modest degree, and learned Zaydis dominated and were the arbiters of these matters. At the top of Yemeni society, the Zaydi leaders felt superior and found it easy to think themselves the best in the best of all known worlds. Largely confined to the highlands and cut off from the outside world, the Zaydis had little opportunity and inclination to compare their life to alternatives the outside world had to offer. They were a proud, inward-looking mountain people with a narrow, parochial perspective.

For its part, the Shafai community exhibited contradictory tendencies of submission and rebellion in the face of Zaydi power and claims to authority. More often than not, the Shafais chose or were forced to accept the imam as their secular ruler, though not as their religious leader. Denied political position and social status, some Shafais turned to trade and commerce, particularly in Taiz and al-Hudayda. Many more emigrated, to Aden and sometimes far beyond, as students, laborers, sailors, merchants, and other businessmen, and were thereby exposed to ...