- 586 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The volume brings together twenty-five of the most influential articles published in the field of development geography since 1960. The first part looks at the origins of development geography and the debates between modernization theorists and radicals that took shape in the 1970s. Thereafter, the book is organized thematically. Geographers have made key contributions to development studies in four major areas, all of which are represented here and include gender and households, development alternatives and identities, resource conflicts and political ecology and globalization and resistance. The book ends with three broad-ranging essays by leading figures in the field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Development by Stuart Corbridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

From Colonial Geography to

Radical Development Geography

[1]

The Degeneration of Tropical Geography

Marcus Power* and James D. Sidaway**

How did colonial and tropical geography as practiced in the aftermath of World War II become development geography by the 1970s? We excavate the genealogy of development geography, relating it to geopolitical, economic, and social traumas of decolonization. We examine how revolutionary pressures and insurgencies, coupled with the eclipse of formal colonialism, led to the degeneration and displacement of a particular way of writing geographical difference of “the tropics.” A key objective here is to complicate and enrich understandings of paradigmatic shifts and epistemological transitions, and to elaborate archaeologies of development knowledges and their association with geography. While interested in such a big picture, we also approach this story in part through engagements with the works of a series of geographers whose scholarship and teaching took them to the tropics, among them Keith Buchanan, a pioneering radical geographer trained at the School of Geography of the University of Birmingham, England, who later worked in South Africa, Nigeria, London, Singapore (as an external examiner), and Aotearoa/New Zealand. Key Words: tropical geography, development geography, postcolonialism.

The order of active differentiation that gets called “race” may be modernity’s most pernicious signature. It articulates reason and unreason. It knits together science and superstition.

—(Gilroy 2000, 53)

The major features of the human geography of Southeast Asia, and the major problems faced by the new states of Southeast Asia, arise from this fact of under-development. . . . Superficial observers have been inclined to explain away this backwardness as the result of a tropical environment or the alleged lethargy of the tropical peoples. That such environmentalist-racist explanations have little validity is clearly indicated by the history of the region which demonstrates the earlier existence in the region of developed and sophisticated societies; it also suggests . . . that one of the major causes of the region’s backwardness was the warping and retardation of economic and social development resulting from the impact of European colonial rule.

—(Buchanan 1967, 19–21)

It was Buchanan who introduced us [as students at the University of Wellington in the 1960s] to Silent Spring, The Power Elite, and so forth and encouraged us to read the American Monthly Review. It was Buchanan whose name we associated with C. Wright Mills, A. G. Frank, and F. Fanon; Cuba, Vietnam, and the Red Dawn in the People’s Republic of China. It is to his credit to remember that this was all before Edward Said and latter day radicals like Harvey.

—(McKinnon 1998, 10)

We expect that most readers of the Annals will share our delight in secondhand bookstores. The story of this article begins (in just such a bookstore) eight years ago in the town of Hay-on-Wye on the Anglo-Welsh border. Since we write as geographers, allow us a few words about this place and its connections. Hay-on-Wye (known in Welsh as Y-Gelli) is an original member of the International Booktowns Movement. A novel variant on place promotion and marketing, this “movement” consists of a network of towns whose role in the international division of labor is to specialize in the sale of used books. Becherel in northern France, Sidney-by-the-sea in British Columbia, and Kembuchi in Hokkadio are three other towns in this expanding association. Hay, however, is the inspiration for them all and now hosts an annual international literary festival. Describing “the pleasures of Hay’s stacks,” Paul Collins (2003), a journalist writing in a national British newspaper, noted how

Hay-on-Wye should have been killed off by the online revolution. A perfectly preserved old market town with some three dozen used bookshops for roughly 1,500 residents, the much ballyhooed Town of Books. . . . Yes it does have that lovely festival. But with services like Adebooks, Alibris, and Amazon, a novice with a credit card can buy any old book they want in minutes. Why spend hours driving to the Welsh border, with no guarantee of finding the books you’re looking for? But then, Hay-on-Wye is not about the books you are looking for: it’s about books that are looking for you. It’s a sanctuary for the books that you would never have thought of looking for in the first place.

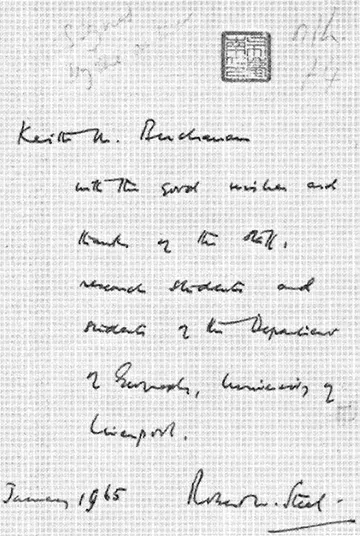

Eight years ago in Hay’s largest used bookstore, one of us (James) discovered and purchased a worn secondhand copy of Geographers and the Tropics: Liverpool Essays (Steel and Prothero 1964), inscribed inside with handwritten words from one of its editors, Robert Steel,1 to Keith Buchanan, thanking him on behalf of the staff and graduate and undergraduate students for his time and contribution during Buchanan’s 1965 visit to the Department of Geography at the University of Liverpool (see Figure 1). Drawing on Latour (1987), Trevor Barnes (2002, 493) has recently drawn our attention to the ways that textbooks circulate and perform disciplines such as geography:

Actors in their own right, textbooks are mobile in that they easily travel—they can be taken off a bookshelf and given to a student, sent long distances in the mail, or stuffed in hand baggage for transatlantic or transpacific journeys— and are immutable in that the distance traveled does not physically corrupt the inscriptions—the same words appear in this paper when printed in Vancouver, or first read in Singapore, or copy edited in London.

In this case, by virtue of the inscription, some moments in the history of movements of this particular book were revealed. Professor Buchanan would probably have carried it to New Zealand—where he was employed at Victoria University—and, years later, when he retired to Wales, perhaps before his return late in life to New Zealand, this copy was sold into the new circuit of movement that is the secondhand book market, ending up in the geography section of one of Hay-on-Wye’s many secondhand bookstores. Here it was picked out again, although, at the time, its significance to us was not quite what it has become through the presentations and (re)writings of this article. Nonetheless, that copy of Liverpool Essays bears witness to Barnes’s (2002, 509) wider point about texts:

[B]ooks may be figuratively buried in university library storage facilities or in secondhand bookshops, but when they are recalled or serendipitously found, and their covers opened, they are alive again having the potential to make a difference to the present, the potential to make the now. Furthermore, when we read those old books it is not because we want to know about the size of raw cotton trade between India and England for 1872–75, or the nature of Walter Christaller’s k-principles, but because they might be creative spurs to thinking about our own present condition. Old books never die. They are always in the wings waiting their chance for one more performance.

We later unearthed Buchanan’s (1940) 10,000-word undergraduate (honors) thesis about the agricultural geography of the Vale of Evesham from the storage areas attached to the map room of the School of Geography at the University of Birmingham in Edgbaston, England. There have been other serendipitous moments over the last few years, when one of us (Marcus) picked up a secondhand copy of Hance’s (1964) The Geography of Africa while taking time-out from the Annual Meeting of the AAG in New York. In the meantime, a return visit to Hay-on-Wye yielded a copy of the fourth edition of Gourou’s (1966) The Tropical World (first published in French in 1948) still bearing a worn dust jacket with a close-up photograph of mangrove-swamps supplied by Sabena (Belgian World Airways). And, when a colleague based at the National University of Singapore, returned to Singapore from a field course in Malacca with a crate of secondhand books, among the collection of books that he purchased there was a termite-gnawed copy of Dobby’s (1955) Senior Geography for Malayans, rescued from further degeneration in the very tropical environments that Dobby sought to describe. We shall return to the mysterious movements of these books later, in our conclusions. Meanwhile, any one of these books could provide a suitable entrée here, for our interest in this article is in tracing aspects of how colonial and tropical geography as performed in the post-World War II era became development geography in the 1960s and 1970s. Attention to this process is productive in part because as Driver and Yeoh (2000, 2) have noted, “work on the genealogy of ‘tropical geography’ during the twentieth century is still in its infancy” (although Forbes [1984] has also done some groundwork). Moreover, such attention to seemingly obscure branches of 20th-century academic geography has the capacity to enrich and disturb wider understandings of paradigm shifts in the discipline.

Figure 1

Inscription to Keith Buchanan from Robert Steel inside a copy of Geographers and the Tropics: Liverpool Essays.

The rise and eclipse of tropical geography is indeed a fascinating and complex story, related as it is to the course of radical geography and the traumas of decolonization. This transformation is both part of the broader creation of institutions and visions of development out of the rubble of empire and war and a disruptive supplement to the history of Anglophone academic geography.2The first part of the article is concerned with the general trajectory of this arena of geographical enquiry. We focus later on the movements and writings of Keith McPherson Buchanan (1921–1998) as a means of exploring the contested and uneven evolution of development geography. This discussion enables us to investigate how tropical and development geographies connected seemingly exotic tropical places with English industrial cities (Liverpool and Birmingham, for example). Our focus is on aspects of Anglophone tropical geography, with some influences on it from Francophone tropical geography, and we must leave aside other traditions (such as those in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Portugal). Our account opens prospects for alternative stories from geography’s recent past; stories that exit and intersect the usual Anglo-American narrative of the history of geographical thought. Here the diversity and range of places in which a certain type of geography was practiced are important. Our conclusions return to these and to the theme of the status of development geography amid questions of difference and alternatives.

The Naissance of Tropical Geography

The identification of the Northern temperate regions as the normal, and the tropics as altogether other—climatically, geographically and morally—became part of an enduring imaginative geography, which continues to shape the production and consumption of knowledge in the twenty-first century world.

—(Driver and Yeoh 2000, 1)

The notion of a tropical geography had a complex path through the twentieth century but became more formalized and more widely recognized after World War II. As Driver and Yeoh (2000) point out at the opening of their brief review, the French geographer Pierre Gourou was one of the most influential and widely read exponents of the pursuit of such kinds of geographical knowledges (Gourou 1947, 1953) and in 1953 (coinciding with the first English translation of his book), new possibilities began to emerge for the publication of tropical geographies with the establishment of the Malayan Journal of Tropical Geography.3 A distinctive modern field of geographical enquiry had coalesced around the signifier “tropical,” supported by journals, teaching, and funding possibilities.

As a starting point in tracing the trajectories of tropical geography, we should recall that the discipline of geography retained a relatively weak position within British universities at the beginning of the twentieth century, and this marginality often extended to the colonial universities (Farmer 1983; Forbes 1984). After the apogee of exploration and discovery in the Victorian era—again best captured in Driver’s (2001) term geography militant—imperial geographies became somewhat less central to the scholarly4 agenda of the discipline in the United Kingdom. Instead, an interest in regional geography was reinforced by the long crisis of the 1930s and the attendant sociospatial disparities, codified as “regional problems” (the English North East, and South Wales for example) and contrasted with “congestion” (the English Midlands and the South East), as well as through the dissemination of Vidal de la Blache’s (1845–1918) methodologies of regional synthesis,5 with their focus on national and regional questions in the metropole rather than the global (which meant colonial) frames of reference. Yet, despite limited support for overseas research during the recession years of the 1930s, some British geographers had remained interested in “colonial” or (as it was already more often being termed) “tropical” geography (Stamp 1938).

It was geographers in a number of other European countries, however, who took the lead in writing tropical geographies, including German language studies of Thailand (Credner 1935) and the Philippines (Kolb 1942), and Dutch work (van Valkenberg 1925) under the auspices of the Netherlands Indies Topographical service. In France, much research focused on Indochina and Southeast Asia through the important works of Charles Robequain (1931, 1944) and Pierre Gourou (1931, 1936, 1940). As has been noted, Gourou (1953) would later write the definitive text of tropical geography (one of the translations and reprints of which we found in Hay-on-Wye), which will crop up again in o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Contemporary Foundations of Space and Place

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I From Colonial Geography to Radical Development Geography

- PART II Gender and Households

- PART III Development Alternatives and Identities

- PART IV Resources Conflicts and Political Ecology

- PART V Globalization and Its Discontents

- PART VI The (Im)possibility of Development

- Name Index