- 124 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This work reviews the theoretical and historical basis of genetic engineering, particularly in regard to genetically modified plants, and details techniques of creating genetically modified organisms. It describes research programs and results in areas such as agro-food, health, and the environment, and examines practical, legal, and ethical questions posed by society and the responses of scientists, legislators, and industry. B&W photographs of equipments are given.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Genetically Modified Organisms by Yves Tourte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1. GENETICALLY MODIFIED ORGANISMS

The now familiar acronym GMO refers to living organisms that have been genetically modified. In the mind of the public, this term is generally associated with commercial crops that have been manipulated in a mysterious and disturbing manner. In fact, GMOs, strictly speaking, involve all living things—including animals, bacteria, or fungi—that have been genetically modified in the laboratory following the deliberate intervention of scientific researchers. The term is rather vague because it supposes that there are, in contrast and in an infinitely more natural way, genetically conforming organisms, which we know there are not. Moreover, scientists can easily demonstrate that there are not enough inhabitants on earth for two persons to have exactly the same genetic make-up. Even identical twins, although they are close to having the same genetic make-up, are differentiated by some errors, uncorrected, that occurred in the duplication of DNA during the single mitosis that separated the first two daughter cells from which they respectively developed. Every individual represents an original recomposition of the genetic make-up of its parents. There is thus no conformity except in the overall expression, which must guarantee the permanence and continuity of the species to which the parents and descendants belong, while ensuring the individual’s constant ability to adapt to variations in environmental conditions.

Here we touch on the two essential properties of the genome: stability and plasticity. This is one of the most beautiful subjects of reflection for biologists, and one that is often offered to the sagacity of students writing biology examinations!

Animal or plant breeders frequently cross genetically very different varieties in the hope of obtaining a manifestation of heterosis. This activity permanently and profoundly modifies the organization of the genome. Even in individual plants belonging to populations that have multiplied by strict autogamy or vegetative propagation, there appears some variability, called somaclonal.

What is true at the individual level is more so on the cellular level. The zygote, which results from the fusion of two gametic cells that are highly differentiated but in very different ways, represents an original genomic composition. The zygote rapidly divides into daughter cells that then enter a process of differentiation accompanied by progressive loss of their totipotentiality. This process seems much more rapid and intensive in animals than in plants. Cell differentiation has long been investigated to find out whether it accompanies a modification that affects the genome in just its expression or in its structure. A partial answer was given in 1997 with the birth of the celebrated cloned sheep Dolly, a product of the union of a nucleus of a differentiated cell and cytoplasm of a female gamete. The answer was only partial because the premature ageing of the sheep could be interpreted as the expression of a modified cell.

Constant modification of a genome thus seems to be the rule and conformity the exception.

In reality, the description of GMOs is much narrower because their creation depends on the calculated intervention of scientists. One definition of GMO is an organism whose genetic material has been modified in a way that is not possible by natural propagation and / or recombination (French law no. 92.654, 13 July 1992). To create a GMO, the researcher must use a technology adapted to a programme or project designed to modify the organization and functioning of the genome of all the cells of the organism including, if possible, the reproductive cells. Genetic modification of only part of the cells results in chimeric organisms that cannot be considered true GMOs. The modification is due to the transfer of a gene taken from cells of another donor organism that must be introduced in the host organism: this is the transgene. This transgene must be expressed in its new environment, at least in a transitory manner and at best in a durable manner. In the latter case, it is often necessary for the transgene to be able to reproduce at the same time as the genome of the host cell; for this, it must integrate itself in the host cell. All these events must be verified. Geneticists set up a range of techniques that will be described in this work and that allow them to understand the future of this transgene and the consequences of its expression in the organism thus genetically modified. Many complementary techniques are available, but they are sometimes very time-consuming. We will see that one of the most delicate problems raised by GMOs at present involves their detection and their identification.

To be considered a GMO, an organism must be living. Thus, products derived from their metabolism or their cadavers are not strictly GMOs even though it is these products found in food that presently seem to pose a problem in the eyes of the public.

Before tackling the problems that GMOs pose in our time, it seems necessary to better understand the principles and methodologies used to create GMOs, particularly the major techniques of molecular biology that biotechnologists use, as well as the intended objectives of their creation. We will speak, later in this work, essentially of genetically modified plants, which are presently most affected by this technology. However, we must discuss bacteria and yeasts, valuable auxiliaries for the creation of vectors and identification of genes without which genetic transformation in plants would be impossible. We will also mention other categories of organisms— prokaryotes, viruses, fungi, and animals—that are affected by this technology and underline the differences in the technical approach and the results obtained. We will look at the achievements, attempts, and promises of these GMOs in large sectors of activity—agro-foods, medicine, and environment—before tackling the uncertainties, the stakes, and the investigations that their presence gives rise to in each of these sectors. We will study the regulatory, judicial, and bioethical responses of societies and nations with respect to GMOs.

GMOs are not the products of chance, as in the fantasies of mischievous science writers. They are the fruits of an evolution of biology in the second half of the 20th century. Let us first look at some highlights of their history.

1.2. A BRIEF HISTORY

GMOs are the product of a discipline of biology called “genetic engineering”, itself an integral part of biotechnology. After having discovered the laws of genetics, it seemed natural that scientists would desire to control them. The first manifestation of this control can be considered the birth of genetic engineering. It is nevertheless very difficult to give genetic engineering a precise date of birth because mastery of the genome, in fact, took a long time to become a reality. Should genetic engineering be traced to the first successful transformation of a bacterium by the intermediary of DNA? If yes, the right answer would be 1944, when O.T. Avery successfully transformed strains of non-pathogenic (avirulent) Pneumococcus strains into pathogenic (virulent) strains by putting the first kind of bacteria in contact with DNA of the second kind in vitro. Only an overall control was achieved, on the population or colony level, and the interpretation was only approximate and incomplete.

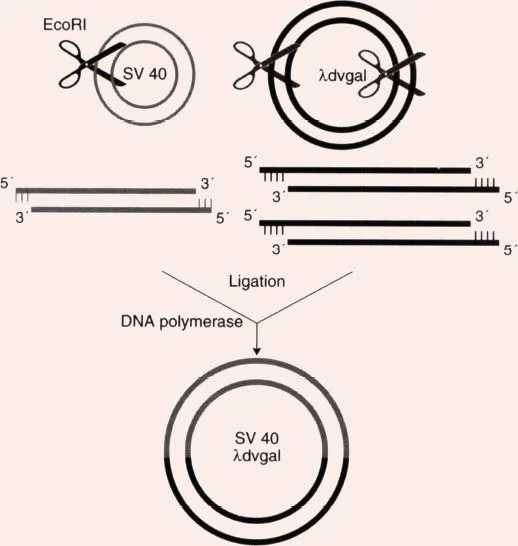

It seems more reasonable to consider that genetic engineering was born in the early 1970s, with the discovery of remarkable tools such as restriction enzymes, a sort of molecular scissors to cut DNA with, and the perfection of the first cloning vectors. Paul Berg presented in 1972 the first studies on cloning, during which he used the first restriction enzyme extracted from the bacterium E. coli, the endonuclease EcoRI, to linearize DNA of a virus (SV 40) as well as to cleave the DNA of a bacterial plasmid carrying a gene for galactose metabolism. Normally, bacteria are equipped with these enzymes to defend themselves against parasitic bacteriophages. Berg thus succeeded in creating the first plasmid vector capable of modifying the genome of a host cell (Inset 1.1).

INSET 1.1

The first recombinant DNA

Paul Berg was the first to carry out a manipulation of DNA cloning. He used the first endonuclease discovered, EcoRI, to linearize the virus SV 40 and to clone a part of the DNA of a bacterial plasmid. This plasmid normally allows the bacteria to utilize galactose (λdvgal). EcoRI can be used to obtain fragments with sticky ends (which was unknown to Berg, who took the trouble of adding complementary sequences designed to link the fragments to one another, whereas the enzyme spontaneously generated such sequences). He thus obtained the first recombinant DNA ligating the bacterial DNA and the viral DNA.

The 1970s were a particularly fertile period for “molecular biology”, in its fundamental aspects as well as for some applications. There was an extraordinary development of research on restriction enzymes extracted from a large number of species of bacteria and capable of cleaving the DNA molecule at highly precise sequences. Some enzymes make straight cleavages whereas others, which are more numerous, have the peculiarity of generating sticky ends, which tend to reassociate spontaneously. These enzymes can thus be used to excise fragments from a DNA molecule and replace them by other fragments cleaved by the same enzyme and carrying other genes. This is the basic principle of genetic modification. Once the new fragments are inserted, they must be able to be conveniently exploited by the host cell and transmitted, during cell division, to two daughter cells (Inset 1.2).

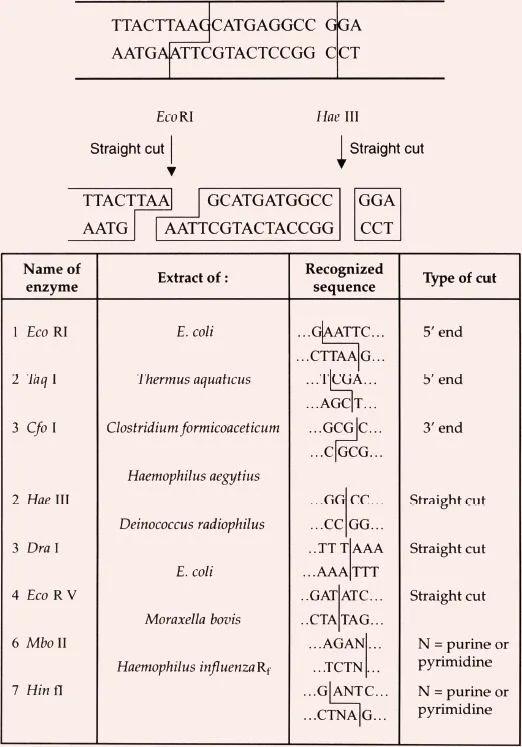

INSET 1.2

Restriction endonucleases

The first diagram shows a staggered cut on the two strands, as with EcoRI; the ends of fragments can spontaneously ligate again.

The second diagram shows a straight cut, as with the enzyme Hae III. The ligation is much more difficult to achieve, impossible in some cases. The table gives some examples of endonucleases and the types of cuts resulting from their use. Today we know of over 100 different endonucleases.

The progress in this field was so rapid that the first private organization based on controlled exploitation of the genome, Genentech, was created in 1976 in the United States by H. Boyer. This first society of biotechnology produced human somatostatin by a genetically modified bacterium (or “reprogrammed bacterium”, as some call it).

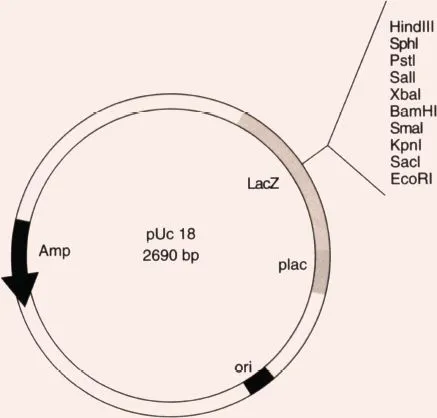

By the end of the 1970s, the bacterial plasmid, for example plasmid pUC 18 (Inset 1.3), which was equipped with its source of replication as well as a polylinker or cloning site and could be opened, closed, cut, completed, and transformed, became a familiar object in all molecular biology laboratories.

INSET 1.3

Plasmid pUC 18

This bacterial plasmid of close to 2700 base pairs, like all plasmids, has a source of replication that ensures that is it is copied, a gene for resistance to ampicillin (amp), the gene lacZ with its promoter (plac) and a multiple site of cloning that allows the insertion of exogenous DNA seauences bv means of specific restriction enzymes.

The transformation of eukaryote cells was achieved in the early 1980s, with the perfection of transfection techniques. It can be said that at this time no biological group refrained from attempts at genetic transformation. In the plant kingdom, genetic transformation of cells became part of the perspective of a new agronomy looking beyond its usual agro-food prospect toward development at the agro-industrial level. As for animal or human cells, their transformation would interest the medical field first of all, i.e., pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. We will see that the development of genetic engineering in these two key sectors of the economy—agro-food and medicine—would be perceived in very different ways by the public.

A third major sector of the economy, that of the environment and all that follows from it for our framework of life, was promptly involved in genetic engineering. Here also, not without polemics and confrontations.

INSET 1.4

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

The thermocycler is an apparatus that allows the alternation of periods of high heat designed to denature DNA, which must then become single-stranded, and cooling periods during which a heat-stable DNA polymerase (extracted from a thermophilic bacterium) synthesizes complementary nucleotides of DNA strands separated during the preceding cycle. The thermocycler does this with very low thermic inertia and for per...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Techniques of Creating GMOs

- Chapter 3. Research Programmes and Results

- Chapter 4. GMOs: Concerns and Remedies

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index