4

Cultural and Cross-National Issues

OVERVIEW

To what extent is there a new culture evolving in cyberspace, with its own values, beliefs, and norms adhered to by its users? Subgroups, such as hackers and cyberpunks, may adhere to different norms than other users. Cyberspace is part of the postmodern epoch, where information and knowledge replace capital and labor. However, whereas geographical boundaries may be overcome, cultural differences could hinder the Internet from becoming an institution with shared values, norms, and rituals. The interrelationship of these issues with cyberspace and culture are outlined and opportunities and risks offered by these developments are discussed (cf. Appendix B).

Part I and chapters 1. through 3. set the stage in so far as they outline how the Internet has offered new opportunities for communicating around the globe. Governments have tried to set policy and regulation where necessary, which in turn has affected the economics of Internet useage by consumers and organizations. Often, however, people are unaware of how cultural differences may affect Internet users. Our values, beliefs, interests, and objectives guide which customs, norms, and rituals we adhere to and perceive as morally acceptable. Accordingly, culture provides the foundation for our understanding of justice and, ultimately, of the law as well as how we interpret and administer our laws (e.g., regulatory concerns). In turn, culture also influences our cyberspace choices, practices, the design of technical systems (e.g., video game entertainment), and the possible development of institutional characteristics for the Internet.

This chapter focuses on cultural and national differences as well as on similarities and how they might influence CMC and the use of the Internet by citizens and organizations. First, a discussion of how culture can be defined is given and television and cyberspace entertainment are used to illustrate similarities and differences between countries. Finally, cyberspace as a cultural genre is discussed and possible future developments are outlined.

THE MEANING OF CULTURE

Any society may be considered as having a variety of cultural “themes,” rather than a single culture. Cultural themes are composed of various interpretations and heterodoxies of the core culture, in addition to any incursions that may have developed around the core, such as the introduction of a new ethnic group. Cultural diversity in countries has been increasing due to the internationalization of business; the workforce has become more variegated due to the entry of guest workers, immigrants, and refugees. Cross-national studies about individual and organizational phenomena are concerned with the systematic study of the behavior and experience of cyberspace participants in different cultures. A brief discussion of the most pertinent cultural issues follows.

Most anthropological studies contain one or more of the following cultural derivatives; symbol (including language, architecture, and artifacts), myth, ideational systems (including ideology), and ritual. Whereas anthropologists and sociologists continue to debate the correct usage and meaning of these concepts, most studies treat them as motivational factors for individuals and groups (Silverman, 1970). Psychologists tend to follow Triandis and Vassiliou’s ( 1972) model whereby a distinction between subjective and objective culture is made. Subjective culture is defined as a group’s characteristic way of perceiving its social environment. For example, office workers could differ in their attitudes toward computers based on demographic characteristics such as gender (e.g., Gattiker, Gutek & Berger, 1988).

In the context of this book, it is assumed that culture represents both a stable and an individual/environmental dimension (objective/subjective continuum using Triandis’ terminology; see Gattiker & Willoughby, 1993 for an extensive discussion of this issue).

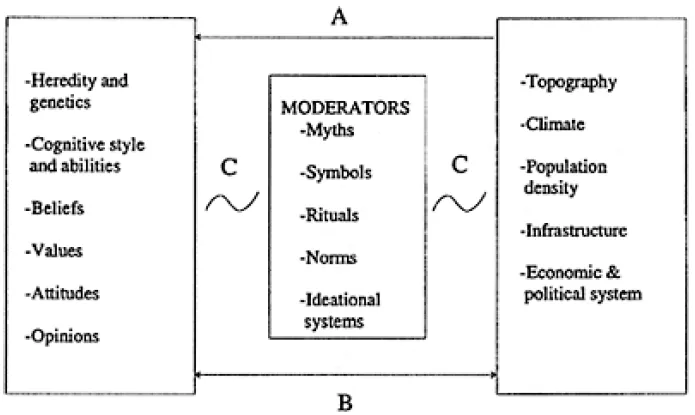

As Fig. 4.1 reflects, the x axis (horizontal) is a continuum that ranges from the micro focus (i. e., the individual) to the macro perspective (i.e., the environment) of a culture; and the y axis (vertical) represents the level of stability of the culture ranging from low stability [e.g., approximate subjec-tive (opinions)] to high stability [e.g., innate subjective (cognitive style)].

FIG. 4.1. Relationship between the micremacro continuum and the degree of cultural stability.

The micro dimension is represented by the cyberspace user whose attitudes and opinions are likely to change frequently during his or her lifetime (low cultural stability), that is, what is “cool and in” today may be “out” tomorrow. The macro side represents the natural and humanmade environment. Whereas topography may remain stable over thousands of years, a country’s telecommunication infrastructure can change rapily after deregulation (e.g., 1997 when the European Union deregulated telecommunications, although the United Kingdom had opened its telecommunication market to competition in 1991). Moreover, if cable operators, railways, and electrical utilities are also allowed to offer telecommunication services to the public, further changes will occur.

Arrow A symbolizes the influence of the natural environment on the individual. For instance, a change in climate may lead to the survival of only those individuals whose genetic makeup, as the result of favorable mutations over generations, has adapted them for survival.

Arrow B symbolizes the bidirectional relationship between the approximate factors, such as the individual’s beliefs, values, attitudes, and opinions about the Information Highway, and the humanmade environment, as represented by the infrastructure and the economic, legal, and political systems of a country. Wave C illustrates the intermediary effect of cultural moderators on the approximate individual factors and the humanmade environment. Accordingly, symbols about Netiquette when sending e-mail may influence how a society responds to a person’s behavior whereas it might be frowned on to send advertising for products via the Internet. Hence, when a couple of lawyers sent advertisements about their book dealing with cyberspace issues via the networks in 1994, people got angry and reinforced the rules by sending them thousands of messages until their mailbox had to be shut down (see also Table 7.4).

The literature does not support the view that cultural moderators and the natural environment affect innate individual factors. However, this does not mean that a certain topography and climate may not foster certain myths and symbols. For instance, the lnuit language contains over 30 words describing snow, and lnuit fairytales likewise reflect the importance of snow and ice.

The left rectangle represents the individual dimension of Fig. 4.1. Hence, its location is to the left (x axis=micro focus), and the stability of these factors decreases from heredity down to opinions (y axis). For instance, public opinion polls show that the electorate frequently changes support for the government in power. In contrast, people’s beliefs are relatively stable and resistant to change (e.g., Rokeach, 1980). This illustrates that when we try to comprehend culture from a micro perspective, we must accept that an individual’s opinions are less stable than his or her belielfs. Moreover, although we can measure genetic factors such as eyesight and reproductive behavior, it is far more difficult to comprehensively assess opinions. Whereas opinions are approximate, heredity and genetic factors are innate; they occur as a result of genetic mutations over generations (Plom.in & Rende, 1991).

The right rectangle in Fig. 4.1 graphically illustrates the environment that is, at the top, natural, and at the bottom, humanmade. Similarly, although the natural parts of the environment, such as topography and climate, are stable over generations and centuries until the next natural disaster, population density or infrastructure, including roads and tlhe Internet, result in the implementation of human actions and policies. To illustrate, low Internet access costs in North America enables users to spend their spare time communicating on chat lines, reading newspapers online, and obtaining information about products made in other countries. In fact, some U.S. data indicate that 10% of people watching TV are surfing on the Internet at the same time (Coffey & Stipp, 1997; Internet users, 1997). Although the infrastructure in Germany allows such behavior, metered local telecommunication costs or cable connection charges prevent German end-users from spending too much time online (see chap. 3, e.g., Table 3.1).

Arrow A symbolizes the unidirectional influence of the natural environ-ment on innate individual factors. For instance, a change in climate may alter a society’s degree of pigmentation over generations.

Arrow B is bidirectional. This demonstrates that approximate factors, such as people’s beliefs or attitudes, influence the humanmade environment, and vice versa. For instance, when the steam train was introduceid, many people believed it to be evil and resisted its development and use. Hence, the development of the infrastructure necessary to the development of the new technology was obstructed by societal beliefs. Medical technology is another example of the contradiction of societal beliefs and technological advances. It is now possible for a 12-week-old fetus to develop in the body of its brain-dead mother until its life may be maintained in an incubator. Such cases have resulted in discussions between politicians, doctors, churches, and the public about the ethics of such action. The cloning of a sheep in England reported internationally in 1997 led to the scientist being invited to a U.S. Senate Hearing discussing ethical issues and the potential of human cloning. It may be inferred that people’s values and beliefs ultimately decide if the medical infrastructure can be used for such procedures. Similarly, the public’s attitudes and opinions influence the content (e.g., pornography) and information offered through the Internet.

Arrow B also indicates that economic, legal, and political systems or the humanmade environment can influence people’s beliefs and opinions. For example, it is illegal to create or distribute malicious software codes and viruses. In other countries, such acts may not be considered illegal, or are not enforced.

Figure 4.1 illustrates the moderating effects of cultural derivatives, as represented by symbols, rituals, myths, norms, and ideational systems. For instance, in the late 197Os, German speaking countries required students who studied business administration and management to demonstrate knowledge about a programming language, primarily Cobol (a norm). In contrast, American universities dropped programming requirements and shifted toward end-user training in applications. Today, German university students may still learn about programming, whereas U.S. business students acquire substantial skills for user applications. This illustrates how changes in the environment (technology and business) can manifest themselves by altering or replacing certain training requirements, whereas new skills may become a norm to secure one’s employment after graduation (Gattiker, 1990b, 199Oc, 1995). This process may also suggest shifts in attitudes and opinions by educators, employers, and students (i.e., Germany focuses on computing science-type training for management students, whereas the United States gears end-user training toward applications in a LAN and PC environment).

Table 4.1 lists and illustrates the objective and subjective dimensions of culture and in combination with Fig. 4.1, permits us to structure our analysis of cyberspace culture somewhat better, as addressed later.

CULTURE AND TV/CYBERSPACE ENTERTAINMENT

Today’s satellite and cable distribution technology has increased the availability of television programming options for households. Particularly, speciality channels (e.g., news, sports, and music) have become quite successful. CNN (all news channel) and MTV (music) were paving the way by being broadcast worldwide. Unfortunately, CNN and MTV offer a fare that is clearly influenced by U.S. culture. Accordingly, CNN offers news very much influenced by the current agenda of U.S. foreign policy whereas MTV shows much music based on U.S. teenagers’ tastes. Having a fully staffed office in London for its European channel does not remove the U.S. cultural influence. However, across non-English speaking Europe, the dominance of British and American music stars is being eroded. Consumers are increasingly buying local music although pan-European stars are emerging and some are even selling in Latin America.

TABLE 4.1Classifying Cultural Variables: Objective and Subjective Culture

Subjective Culture

- subsistence system (methods of exploitation of the ecology to survive, such as telecommunication infrastructure);

- cultural system (humanmade environment, religion);

- social system (patterns of interaction, such as roles and stereotypes);

- interindividual system (e.g., social behaviors on the Internet);

- individual system (e.g., perceptions, attitudes and beliefs of what is or is not morally acceptable behavior, such as pirating software).

Objective Culture

- ecology (e.g., the physical environment, resources, geography, climate, fauna and flora);

- objective portion of the cultural system or infrastructure (e.g., roads, tools, machines. CIS, and factories).

Note. This list of variables is adapted from Triandis (1977, p. 144) and Gattiker and Willoughby (1993); expansions and additions have been made. In the context of this book, I discuss the objective dimension of culture (e.g., chap. 3) and telecommunication infrastructure) as well as the subjective one (e.g., chap. 4, crime and terror). In this chapter, I focus on the subjective side of culture.

This apparent paradox has happened during a time whereby geographical boundaries have become less of a hurdle against reaching beyond national markets thanks to technology (e.g., TV and Internet) but, in contrast, cultural differences in tastes such as music have resulted in further segmentation of markets. Accordingly, music channels with a substantial local content (e.g., Via in Germany) and news channels focusing on national or regional issues (e.g., ntv Germany) have blossomed. Moreover, this apparent preference of a substantial portion of the consumer market for local fair in music and TV news is also reflected by cyberspace content. For instance, besides being in German, AOL Germany’s content differs substantially from its U.S. counterpart. The German AOL joint venture with Bertelsmann is offering various discussion groups on educational or job-re-lated issues that make up a far greater portion of the total number of such lists on Germany’s AOL than is the case in the United States.

This suggests that although culture and cyberspace developments are interrelated, we need to discuss the postmodern condition and its effect on how we perceive and evaluate the world we live in (cf. Sim, 1992). In turn, this might explain why cultural differences have not become less but more distinct in recent decades even though technology may have removed physical barriers (e.g., ease of travel or communication) suggesting an approximation of values in neighboring countries (e.g., EU member states). The modern is an unprecedented effort to explain the world, to conquer uncharted territory and spheres of life while transforming it at the same time. Industrial society is based on technology that is used to improve the allocation of capital and labor (cf. Lyotard, 1984, p. 45).

Table 4.2 defines postmodernism, postindustrial culture, and cyberspace culture. Of course, its appropriateness can be debated. Some would argue that we cannot define cyberspace culture and structure untilwe have experienced it as a stage in our society’s dev...