- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The book appears in two volumes, the first dealing primarily with chemical and structural aspects, and the second with metabolic aspects. The purpose is not only to review recent work on chemical and physiological aspects of bilirubin scructure and metabolism, but also to emphasize the importance of methodological advances and their potential in future studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bilirubin by Karel P. M. Heirwegh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Alternative & Complementary Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Heme Degradation and Bilirubin Formation

S. B. Brown and R. F. Troxler

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction

II. Hemoprotein Turnover

III. Sites of Heme Breakdown and Bilirubin Production

IV. Coupled Oxidation Systems

V. Enzyme Systems

A. Early Work

B. Heme Oxygenase

C. Enzymic Reduction of Biliverdin

VI. Mechanism of Heme Conversion to Bile Pigment

A. Mesohydroxylation and Iron Oxophlorins

B. The Role of Iron in Heme Degradation

C. Role of Oxygen

D. Role of Axial Ligands and Heme Dimerization

E. 18O Labeling Experiments

F. The Regioselectivity Problem

G. Summary of Mechanism

References

I. Introduction

The mode of formation of bilirubin in mammalian systems has received considerable attention over many years. This attention has been focused largely because of the health related aspects of bilirubin structure and metabolism, but also because of the challenging chemical problems associated with the mechanism of heme degradation. Several excellent reviews dealing with the subject from both physiological and chemical viewpoints have been published in the past decade.1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 The purpose of this article is to outline the current state of knowledge of heme catabolism and bilirubin formation, particularly from a mechanistic standpoint. Recent experiments and theories in this field have been primarily directed towards determination of mechanism and there is now a substantial body of evidence to suggest that heme catabolism in biological systems occurs by essentially the same mechanism as heme degradation in chemical model systems.

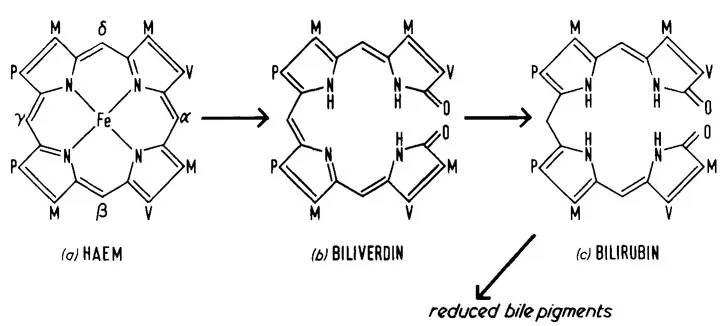

A great deal of work both structural and metabolic has indicated that, in mammalian systems, all of the bilirubin produced is derived from degradation of protoheme (Figure 1). This work has been extensively reviewed1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 and no attempt will be made here to present a comprehensive or critical account of the evidence for the product-precursor relationship between heme and bilirubin. It is also generally accepted that the immediate tetrapyrrolic precursor of bilirubin is the blue-green pigment, biliverdin, as shown in Figure 1. In mammals, direct evidence for the intermediacy of biliverdin is not easy to obtain, since normally it is not present in isolable amounts and, although it is sometimes present in diseased states, it is difficult to be certain that some of this material is not formed by reoxidation of bilirubin. However, there is no doubt that, in mammals, many tissues contain the enzyme biliverdin reductase which converts biliverdin to bilirubin,3, 4 and 5 although the specificity of this enzyme appears rather broad. In addition, intravenously administered biliverdin is rapidly converted to bilirubin. Taking into account the additional facts that in many species biliverdin is the end product of heme catabolism (see below) and that the number of double bonds in biliverdin is appropriate to a direct heme cleavage product (bilirubin contains one less), the evidence for biliverdin as the precursor of bilirubin is very strong. Because of its remarkable intramolecular hydrogen bonding (Chapter 1, Volume I), bilirubin free acid is virtually insoluble in water and is potentially highly toxic especially in the neonate. Efficient elimination of bilirubin is therefore essential and this is accomplished by conjugation with polar substances such as glucuronic acid. The enzymic formation of bilirubin conjugates (see Chapter 3, Volume II) is the last step in heme catabolism carried out by mammalian enzymes, since the further reactions shown in Figure 1 and discussed in detail in Chapter 4, Volume II are carried out by the intestinal flora.

A novel feature of the initial reaction of Figure 1 is the elimination of a methene bridge carbon atom of heme as carbon monoxide, leading to the remarkable situation where the highly functional heme is converted to two potentially toxic metabolites. Approximately 0.4 g of bilirubin per day is produced by normal adult humans and this corresponds to about 15 ml of carbon monoxide measured at STP. At any time this carbon monoxide accounts for about 1 to 2 ppm of exhaled gases (a level which is readily measurable). Indeed, hemolytic states may be detected in terms of an increase of exhaled carbon monoxide, although careful corrections for environmental factors such as cigarette smoking must be made. Of course, this level of carbon monoxide is not acutely toxic, since the oxygen concentration in air is about 200,000 ppm and, even allowing for the greater affinity of carbon monoxide, very little hemoglobin is in the carbonmonoxy form. In addition to biliverdin and carbon monoxide, iron is also a product of heme catabolism. Unlike the two former catabolites however, iron is not eliminated from the organism, but is retained in the iron pool presumably being returned to the ferritin stores, probably via transferrin. Indeed the whole of the heme synthetic and degradative pathways can be written as an iron cycle in which iron is conserved.

FIGURE 1. Structure of the principal tetrapyrrolic pigments involved in heme catabolism (M, -CH3; V, -CH=CH2; P, -CH2CH2CO2H).

In principle, because of the asymmetrical arrangement of side chains around the heme molecule (Figure 1) degradation could lead to four possible biliverdin isomers and hence bilirubin isomers, according to whether the α, β, γ, or δ methene bridges are attacked. However, the bilirubin found in mammalian bile consists almost exclusively of the α isomer as shown in Figure 1. Similarly, the biliverdin of avian bile contains, for all practical purposes, only the α-isomer.6 Clearly a complete mechanism for heme catabolism must account for this selectivity (sometimes termed regioselectivity).

This chapter is concerned primarily with the mechanism of formation of bilirubin both in vivo and in vitro. However, it would be wrong to imply thereby that bilirubin is the only bile pigment of importance in biological systems. Certainly it is not the most abundant, and it appears to serve no function other than in providing a pathway for the removal of unwanted heme. This is obviously a particularly significant process for animals containing hemoglobin, although it is noteworthy that for many species (including birds and amphibians) biliverdin is the final pigment produced, the formation of bilirubin being a particular characteristic of mammals, and possibly also reptiles and some fish. On the other hand, plant bile pigments (so called because of their close structural relationship to the mammalian bile pigments) are probably the most abundant in the biosphere and serve important functions in photosynthesis and photomorphogenesis.7 In certain lower plants including the red algae (Rhodophyta) and in the blue-green algae (Cyanobacteria) the primary photosynthetic antennae pigments are proteins with covalently linked chromophores closely related in structure to biliverdin. These phycobiliproteins include phycocyanin and allophycocyanin, associated-with the bile pigment, phycocyanobilin (Figure 2) and phycoerythrin associated with phycoerythrobilin (Figure 2). In higher plants, the photoactive pigment phytochrome is also a bile pigment protein complex8 (chromophore structure shown in Figure 2). It is highly significant that, like the mammalian bile pigments, those found in plants and cyanobacteria are also IXα isomers. A detailed discussion of the formation and role of these plant bilins is beyond the scope of this chapter, although it should be noted that the photosynthetic bile pigments, particularly those in Cyanobacteria, occurred very early in evolution and it seems probable that the modern pathway for bile pigment formation in mammals evolved from this primitive pathway in Cyanobacteria. Although potentially, chlorophyll degradation m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Heme Degradation and Bilirubin Formation

- Chapter 2 Aspects of Bilirubin Transport

- Chapter 3 The Role of Conjugating Enzymes in the Biliary Excretion of Bilirubin

- Chapter 4 Formation, Metabolism, and Properties of Pyrrolic Compounds Appearing in the Gut

- Chapter 5 The Role of Kinetic Analysis and Mathematical Modeling in the Study of Bilirubin Metabolism In Vivo

- Chapter 6 Physiology and Disorders of Human Bilirubin Metabolism

- Index