![]()

Part 1

General issues about learning languages with computers

![]()

1 Languages and literacies for digital lives

Mark Pegrum

UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA, AUSTRALIA

Introduction

In a world woven ever more tightly together through physical travel and migration networks, complemented by virtual communication networks, the need to operate in more than one language is greater than ever. But language alone is not enough. A knowledge of how to negotiate between diverse cultures, and a facility with digital literacies, are equally in demand on our shrinking planet. Thus, at the very moment when automated translation technologies are eroding some basic language learning needs for some individuals (Orsini, 2015; Pegrum, 2014a), language teachers find themselves with an ever more diverse portfolio of responsibilities for teaching language(s), culture(s) and literacies.

For some time now, language teachers have been going beyond the teaching of language to emphasize culture and, especially, intercultural communicative competence (Byram, 1997). In a digitized era, it is equally necessary to go beyond the teaching of traditional literacies to emphasize digital literacies (Dudeney, Hockly & Pegrum, 2013). Digital literacies are part of the broad set of 21st-century skills increasingly seen as essential for global workplaces, as well as for our personal lives, social lives and civic lives in local, national and regional communities, and ultimately the global community. The 21st-century skills include creativity and innovation, often linked to entrepreneurship (Zhao, 2012), along with critical thinking and problem-solving, collaboration and teamwork, and autonomy and flexibility (Mishra & Kereluik, 2011; P21, n.d.; Pegrum, 2014a); all of these are underpinned by digital communication tools and the literacies necessary to use them effectively. In short, students need to learn how to interpret the messages that reach them through digital channels, and how to express their own messages digitally. Digital literacies must be taught alongside language and more traditional literacy skills.

This new emphasis on digital literacies builds on decades of growing emphasis on multiple literacies. These have included, notably, visual literacy and multimodal (or multimedia) literacy, reflecting the shift from a word-centric to a visual culture (Frawley & Dyson, 2014); and information literacy, reflecting the shift from a culture of limited publication channels to an online culture with few gatekeepers (Dudeney et al., 2013). Thus, the concept of multiple literacies – or even multiliteracies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; Kalantzis & Cope, 2012) – which are fostered and facilitated by digital technologies is not new, though arguably there is still a lack of appreciation of the significance of the digital literacies skillset. Meanwhile, today’s digital communication networks are continuing to build the importance of some of these literacies, as well as highlighting literacies of which we previously had little awareness, and introducing literacies which could not have existed prior to the digital era (Pegrum, 2014b).

Keeping up with new literacies is a pressing issue for educators. It has been suggested that there is a “continuous evolution of literate practice that occurs with each new round of ICTs” (Haythornthwaite, 2013, p. 56), linked to the “‘perpetual beta’ that is today’s learning and literacy environment” (ibid., p. 63). Notwithstanding recent initiatives to include a greater focus on digital tools in national curricula, teacher standards and teacher development programmes (Pegrum, 2014a), instances of effective engagement with digital literacies and digital practices are still limited, perhaps most notably at tertiary level (Johnson et al., 2014; Selwyn, 2014), where there has traditionally been a lesser focus on teaching development. As the pressure grows for educators to become designers of customized learning environments and tailored learning experiences for their students (Laurillard, 2012; Pegrum, 2014a), digital literacies will need to become a core consideration, not just in terms of student learning outcomes, but in terms of educator development and learning design.

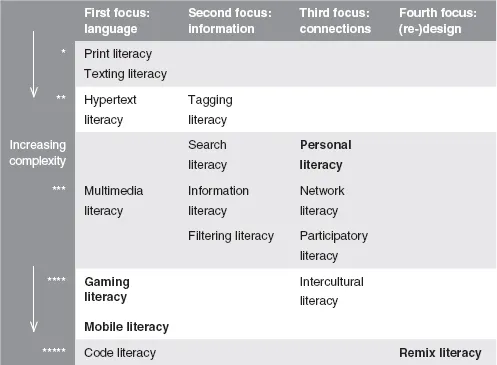

Drawing on numerous preceding discussions, Dudeney et al.’s (2013) framework of digital literacies (see Figure 1.1) provides an overview of the key points of emphasis that language teachers and students need to consider within the landscape of digital literacies. These are divided loosely into four focus areas, though of course neither the focus areas nor the individual literacies are mutually exclusive, but rather intersect in multiple ways. In this chapter, we will examine illustrative examples of key literacies from each focus area, investigating how they support language comprehension and production. Along the way, we will consider newly emerging literacies not included in the original framework. We will also make frequent reference to mobile literacy, one of several macroliteracies indicated in bold in the framework, given that it is now evolving into perhaps the most significant literacy skillset of our time – one that, like all macroliteracies, pulls together the other literacies.

Language-related literacies

The first focus area is related to language, and the communication of meaning in channels which complement or supplement language. While it may seem strange to start a catalogue of digital literacies with print literacy, it remains core to communication online (Pegrum, 2011), and can be practised and honed on a plethora of social media platforms. That said, it is important to remember that print literacy takes on new inflections online; we read and write differently in digital channels compared to paper channels (Baron, 2008; Coiro, 2011), and there may be disadvantages to reading on small screens which impede our overview of the shape of a text (Jabr, 2013; Greenfield, 2014), or reading hypertext peppered with links that reduce our focus on the content at hand (Carr, 2010; Greenfield, 2014).

Multimodal literacy

But language alone is no longer regarded as sufficient to carry meaning in a culture that has shifted from “telling the world” to “showing the world” (Kress, 2003), a process facilitated by digital tools that make it easy to create and share multimedia artefacts (Takayoshi & Selfe, 2007). Multimodal, or multimedia, literacy, which involves drawing on different semiotic systems (Bull & Anstey, 2010) to interpret and express meaning in formats ranging from word clouds through infographics to digital stories (Pegrum, 2014b), is crucial to support both language comprehension and production online. With the help of teachers, students need to develop the ability to choose appropriate representational modes or mixtures of modes, grounded in a solid understanding of their respective advantages: “When is text the best way to make a point? When is the moving image? Or photos, manipulations, data visualizations? Each is useful for some types of thinking and awkward for others” (Thompson, 2013, Kindle location 1666). Communication of meaning, whether in on-the-job, personal or public settings, increasingly requires a sophisticated consideration of audience, purpose, genre, form and context (Conference on English Education Position Statement, 2005, cited in Miller & McVee, 2012, Kindle location 193). In essence, students need to become designers of meaning:

If students need to become designers, they also need to become disseminators of meaning through their designs, engaging in the social literacy practices that have become a fundamental part of everyday communication (Jenkins, Ford & Green, 2013; Miller & McVee, 2012). In this way, multimodal literacy flows into network literacy.

Current and emerging technological developments point towards a growing role for multimodality in meaning-making. With the spread of mobile smart devices, real-time multimedia recording, on-the-fly editing and near instantaneous dissemination are becoming an intrinsic part of constructing, reflecting on and sharing our experiences, opinions and learning; while augmented reality apps can already layer textual and multimedia information over real-world environments, effectively interweaving multimodal representations of reality with reality itself (Pegrum, 2014b). Thus, multimodal literacy also feeds into mobile literacy. In other developments, 3D printers will soon make their way into our lives and our classrooms, raising new questions: “What literacy will 3-D printing offer? How will it help us think in new ways? By making the physical world plastic, it could usher in a new phase in design thinking” (Thompson, 2013, Kindle location 1688). Communicative design will thus expand into 3-dimensionality, while work currently underway on devices that can simulate smell and taste (Woodill & Udell, 2015) will expand multimodality itself far beyond our present understandings. In the process, multimodal literacy will become an ever more important complement to language comprehension and production.

Code literacy

There is little doubt that multimodal literacy can be enhanced by a degree of code literacy, that is, the ability to read and write computer language. Without coding skills, our digital communications are restricted to the templates provided by commercial organizations and the channels sanctioned by political institutions (Pegrum, 2014b). A familiarity with code changes this. “It doesn’t take long to become literate enough to understand what most basic bits of code are doing” (Pariser, 2011, Kindle location 3076) and, from there, to begin tweaking and modifying our digital communications to express our messages as precisely as we wish, and disseminate them as widely as we wish. If students are to take full control as digital designers of meaning, they must simultaneously learn to be designers of the channels through which meaning is communicated.

Awareness of code literacy has recently been boosted by recognition from senior politicians, including U.S. President Barack Obama’s promotion of Code.org’s Hour of Code campaign (Finley, 2014), UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s support for the same campaign and the introduction of coding into the National Curriculum (Gov.uk, 2014), and Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s endorsement of coding at the launch of Singapore’s Smart Nation vision (Lim, 2014). Such projects follow the lead established by countries like Israel and Estonia (The Economist, 2014; Olson, 2012), and dovetail with wider international initiatives like Codecademy (www.codecademy.com) and Mozilla Webmaker (webmaker.org). Moreover, they fit with a trend towards setting up self-directed makerspaces in libraries, colleges and schools (ELI, 2013; Johnson et al., 2014); here, the tools are made available to create with technology, where ‘creating’ can range from designing apps (an increasingly critical skill in our mobile era, and an increasingly critical component of mobile literacy) through to building machinery.

“Do you speak languages or do you code languages?” asks a recent British Council poster. The implication is clear: it is possible, and even necessary, to do both. Speaking human languages is important for communicating precisely and widely in a globalized era; coding computer languages is important for communicating precisely and widely in a digitized era.

Information-related literacies

The second focus area is related to finding, evaluating and cataloguing information, crucial skills in a world where information is ubiquitous, but where its quality and value must be established by its end users.

Information literacy

According to the ‘extended mind’ theory of cognition, we have always outsourced elements of our cognition in order to scaffold our thinking (Thompson, 2013), with printed books being perhaps the most obvious example of external memory devices. Printed materials already demand that we bring information literacy skills to bear on the content we read:

Yet the need for information literacy skills is now exponentially greater thanks to the advent of the internet, where almost anyone can publish almost anything at any time. Critically evaluating content is thus an integral part of digital reading comprehension; and this may include bringing a critical eye to bear on potentially deceptive or distracting multimedia elements (requiring multimodal literacy); on the underlying structure of the communication (requiring code literacy); and on apps that interweave geotagged information – that is, information with a geographical address (Pegrum, 2014b) – with the real-world settings to which it refers (thus feeding into mobile literacy).

Despite the protestations of some technological enthusiasts, the possibility of looking up almost any fact online does not amount to a valid argument against learning facts (Pegrum, 2011). After all, the ability to critique information is dependent on a prior baseline of knowledge or, perhaps more accurately, an existing conceptual framework based on prior knowledge. This is what enables us, and of course our students, to ask appropriate critical questions and, having satisfied ourselves of the reliability of newly encountered facts or ideas, to connect them to our existing understanding. In the end, it is the ability to make connections that is essential:

Indeed, if used appropriately, our new technological tools may facilitate this process of co...