![]()

Chapter 1

The Rio Hondo Project in Northern Belize

Mary DeLand Pohl1

Introduction

Changes in the orientation of archaeological research in the post-World War II period affected Maya studies. The cultural ecological perspective, which was rising to prominence, put an old debate in bold relief: How had this prehistoric civilization adapted to the tropical forest environment? How could swidden cultivation have sustained the unexpectedly high population densities that settlement pattern studies appeared to be revealing? Had the ancient Maya practiced some form of intensive agriculture? Archaeologist Dennis E. Puleston went to the Maya Lowlands to investigate geographer Alfred H. Siemens's reports of possible intensive agriculture ("ridged fields") seen from the air and to study prehistoric Maya cultivation and civilization from a cultural ecological perspective. Siemens and Puleston formed the Rio Hondo Project and focused their research on northern Belize.

After Puleston's death in 1978, Mary Pohl assumed responsibility for carrying out analysis of the data, and she made a trip to Belize to gather additional information in 1980. This volume presents the results of the Rio Hondo Project field research on Albion Island in northern Belize from 1973 to 1980 with the addition of selected results from Pohl's continuing work in northern Belize.

As we analyzed the data, we found that our interpretations of the development of wetland agriculture were different from Puleston's. We were not able to verify the idea that the Maya had built up artificial planting platforms in wetlands. Instead we concluded that ancient farmers first practiced flood-recessional agriculture on peats in sawgrass marshes about 3000 years ago (calibrated date) and perhaps earlier. By the Late Preclassic period the Maya began to ditch their wetland fields in response to rising water levels. The fields eventually ponded over, but farmers continued to cultivate wetlands, sometimes using ditches for drainage, at the end of the Late Classic period when water levels stabilized.

We have also reformulated the theoretical orientation of the research. Puleston's primary concern was with population ecology and how the Maya fed themselves during peak densities in the Late Classic period. We are more concerned with political competition (Brumfiel 1983:266; Wolf 1982:80) and how prehistoric agriculture fed its development during the Preclassic period.

We hypothesize that the combination of wetland and swidden farming provided reliable surpluses that underwrote the emergence of political competition. Successful farmers turned relative rank to absolute rank (Friedman 1979) and extracted surplus from other farmers through a patron-client relationship that centered on Maya religion and warfare (Farriss 1984). Elites also found a source of additional support by monopolizing productive wetland fields (Marcus 1983). Furthermore, intensive agriculture (ditched fields) that emerged in the Late Preclassic period tied farmers to the land and made them both vulnerable to domination by self-aggrandizing elites and more dependent on them for the protection of their agricultural investment (Gilman 1981).

The Rio Hondo Project Research

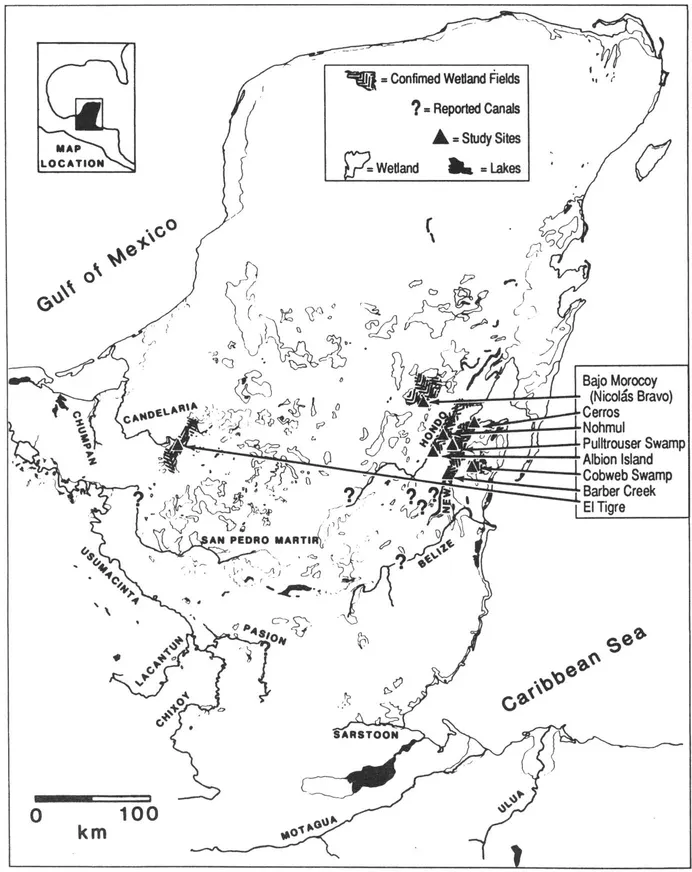

In 1968, Alfred H. Siemens first recognized patterns of ancient fields in the Maya Lowlands from the air over Campeche, Mexico. He enlisted the aid of Dennis E. Puleston to study these features, first near El Tigre along the Candelaria River of Campeche (Siemens and Puleston 1972) and later along the New and Hondo rivers of northern Belize. The latter effort was organized as the Rio Hondo Project.

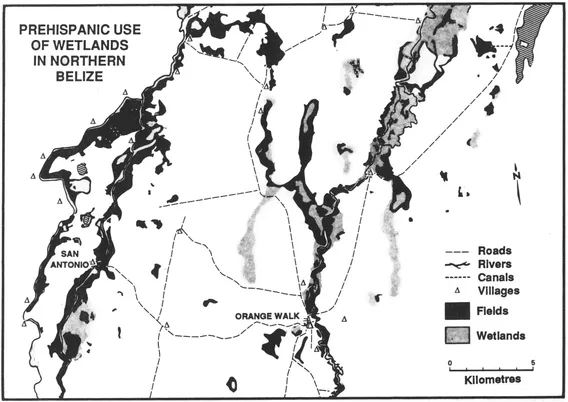

Siemens and Puleston co-directed two principal field seasons in 1973 and 1974. The objectives of the research were to determine the extent of wetland agriculture in northern Belize through ground survey and to excavate the fields themselves at San Antonio Rio Hondo on Albion Island (Figure 1.1). Aerial photography, together with pace and compass mapping (see Siemens 1982), revealed that canals covered the wetlands of northern Belize (Figure 12). The excavations (Puleston 1977,1978) centered on fields in two areas northeast and southwest of the village of San Antonio Rio Hondo (Chapter 8). One of the unique results was the recovery of abundant plant macrofossils (Chapter 10) and wooden artifacts including a hafted axe, a small wooden "paddle," a boomerang-like artifact, and a number of cut stakes and posts (Chapters 8,9, and 10).

Although Siemens and Puleston focused initial research on the ancient fields, the eventual goal was to relate cultivation practices to settlement. Bruce Dahlin and Suzanne Lewenstein (Chapter 13) initiated a settlement pattern survey across Albion Island, and Joseph Ball has analyzed the ceramics (Chapter 14).

The Rio Hondo Project was an early model of multi-disciplinary research on the ecology of agriculture in the Maya Lowlands. During the 1973 and 1974 seasons, geologist J. Piatt Bradbury went to Belize to take cores in Laguna de Cocos, which formed the basis for paleoenvironmental studies (Chapters 6 and 7). Botanists Barbara Coffin (Chapter 4) and Philip Leino (Chapter 5) analyzed the present-day vegetation of the area while Gerald Olson (Chapter 3) examined soils. Later,in 1977,Puleston invited field pedologists Pierre P. Antoine and Richard L. Skarie to conduct further studies of soils in wetlands south of San Antonio, and soil chemist Paul R. Bloom analyzed the samples in the laboratory (Antoine, Skarie and Bloom 1982).

After Puleston's death, Pohl, who had joined the Rio Hondo Project as a graduate student in 1973, and Bloom found that they could not correlate the new soils data from south of San Antonio with Puleston's field notes on earlier excavations north of the village, The samples that

Figure 1.1. Wetland fields in the Maya Lowlands. Adapted from Pope and Dahlin nd. In northern Belize Maya cultivated wetland peats about 1000 B.C. They ditched fields for drainage in the Late Preclassic and Early Classic periods (perhaps AD.0-550) and probably in Terminal Late Classic/Early Postclassic times (perhaps AD. 900-1000 or later).

Puleston and his co-workers had collected were still in large part unanalyzed. Moreover, systematic information on soils, pollen, and molluscs had never been gathered north of the village.

In 1980, Pohl returned to San Antonio with Bloom and field pedologist Cynthia Buttleman to conduct limited excavations north of the village and to collect soil (Chapter 8), pollen (Wiseman, Chapter 11), plant macrofossil (Miksicek, Chapter 10), mollusc (Covich, Appendix 83), and ceramic evidence (Ball, Chapter 14) necessary to interpret the San Antonio excavation locality. Pohl also made arrangements for the completion of analysis of the data Puleston had collected on Albion Island.

The Setting

A change in the channel of the Rio Hondo, as yet undated, formed Albion Island. The old channel, which now resembles a lake more than a river, borders the island on the south, and the younger main channel flows to the north. The present-day village of San Antonio, where excavations in wetland fields were located, lies on the secondary channel at 18. 10'N, 88. 40'W. The height of the river there is 2 m above sea level, and from San Antonio the river flows 75 km to Chetumal Bay in the Caribbean Sea, resulting in a very low river gradient.

The climate is tropical wet-dry (Am) according to the Koeppen classification. Rainfall data recorded from 1965-1970 at Yo Creek near the site of Cuello indicate a well-defined dry season from November into May and a wet season from June through October. Mean rainfall was as low as 11 mm in April. The wet season has a distinct double peak with a mean of 234 mm in June and 269 mm in September (Walker 1973). Rainfall records for the Orange Walk District as a whole indicate significant variability from one year to another (Johnson 1983:10). The mean annual temperature exceeds 24.C (Wright et al. 1959). The vegetation of northern Belize is semi-deciduous tropical forest (see Chapters 4 and 5).

The cultural setting of Albion Island (Figure 15.1) places our research near sites that are important in the development of prehistoric Maya culture. Cuello (Hammond et al. 1979), the nearest excavated

Figure 1 2. Map of ditched features in the vicinity of Albion Island, northern Belize (courtesy of A H. Siemens)

site, has a sequence extending back to the early Middle Preclassic period (Andrews, nd.) and represents some of our earliest evidence for settled life of agriculturalists in the Maya Lowlands. Sites such as Nohmul (Hammond 1985; Hammond et al. 1987) to the north of Albion Island, Cerros (Freidel 1979, Robertson and Freidel 1986) to the north on Chetumal Bay, and Lamanai (Pendergast 1981) to the south on the New River Lagoon demonstrate that stratified society (as marked by pyramids, patio-type residential groups, and decorated, special function ceramics [Robertson 1983]) crystallized in the Late Preclassic period as in certain other parts of the Maya Lowlands. In this report we will examine the relationship of environment, culture, and agriculture.

Research on Lowland Maya Wetland Agriculture

We use the term "wetland agriculture" for cultivation in soils that are inundated seasonally or perennially. Our "wetland agriculture" includes flood recessional agriculture (Orozco-Segovia et al. nd; Wilk 1985), ridged fields (Siemens and Puleston 1972), raised fields (Turner and Harrison 1983), and drained fields (Lambert et al. 1984). "Upland agriculture" is swidden agriculture on drylands.

Siemens's initial discovery of microrelief patterns along the Candelaria River suggestive of human activity in wetlands was accepted as such. Nevertheless, Siemens and Puleston's (1972) published report ascribing an agricultural origin to the landforms was met by some skepticism. J E S. Thompson (1974) suggested that the canals were ...