- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wet Site Archaeology

About this book

This volume, the result of an International Conference on Wet Site Archaeology funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, explores the rewards and responsibilities of recovering unique assemblages from water-saturated deposits. Characteristics common to all archaeological wet sites are identified from Newfoundland to Chile, Polynesia to Florida, and from the Late Pleistocene to the Twentieth Century. Topics include innovative excavation and preservation methods; the need for adequate funding to preserve and analyze the abundant biological and cultural remains recovered only at archaeological wet sites; expanded knowledge of past environments, subsistence, technologies, artistic expressions, skeletal structure, and pathologies; the urgency to inform developers and governmental bodies about the invisible heritage entombed in wetlands that is often destroyed before it can be investigated; a formula for establishing priorities for excavating wet sites; and how to determine when enough of a wet site has been sampled.Many famous sites and discoveries are described in this volume, including Herculaneum, Hoko River, Hontoon Island, Key Marco, Monte Verde, Ozette, Somerset Levels, Windover, bog bodies of Northern Europe, and lake dwellers of Switzerland. Professional and amateur archaeologists, as well as anyone interested in archaeology or the significance of wet site archaeology will find this book fascinating.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wet Site Archaeology by Barbara A. Purdy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Droit & Science médico-légale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A WETLAND PERSPECTIVE

WETLANDS, those flat dreary waterlogged lands that are found in many parts of the world, do not appeal to everyone. Attractive to some, but unloved by many, wetlands conjure an overwhelming vision of endlessness and, to some, even a malevolence. Their dark fields, dank vegetation, and swirling mists can create a lack of focus that is unnerving when first encountered. One of Europe’s largest wetlands, the Fens of eastern England, has inspired this description:

And what are the Fens, which so imitate in their levelness the natural disposition of water, but a landscape which, of all landscapes, most approximates to nothing? Every Fenman secretly concedes this, every Fenman suffers now and then the illusion that the land he walks over is not there, is floating…. (Swift 1984).

Yet within these wetlands, whether they be swamp, marsh, fen or bog, landlocked, estuarine or coastal, is sheltered a myriad of wildlife unseen in other environments. Within the unprepossessing swamps and bogs there also lie vast arrays of cultural material, unique in the surviving world of ancient human craftsmanship. Also held in quiet balance in the marshes and bogs all over the world are the waters upon which we depend, cushioned against too ready a release and flooding, filtered to purity, and held in even flows for an unappreciative mankind. All of these wetlands are at risk today, threatened by modern life; many have perished and lie exposed, withering away in the winds, no longer housing life either present or past. There is no more depressing scene than a dead and abandoned wetland.

Other wetlands in a more restricted archaeological sense include drowned regions, lands once dry and inhabited by all manner of life until flooding by rising lakes or seas or collapse or subsidence of land, sealed them with waterborne silt or peat formation, or buried them in depths of water with sand or gravel. Here too the tide of modern life erodes, with quarrying on land and under the sea, alteration of natural water levels, or imposition of roads, factories or houses upon drained lands. Such wetlands have less impact upon natural wildlife but their cultural importance is as great as that of swamp or bogland.

The reason why we as archaeologists are interested in all these wetlands is obvious. But even without an accompanying cultural element, wetlands should interest us as part of living populations and societies. Wetlands are the last refuge of a multitude of plants and animals once widespread and now threatened by extinction. They also represent a living model of that environmental change and impact which we humans profess to comprehend in the dead world. For archaeology, the wetlands of the world hold the key to understanding past human behavior. No one could argue that this is as important as nature conservation or water purification, yet in its way it has a claim to be so elevated; the relevance of the past to the present has been debated many times and will not be repeated here.

What wetland archaeologists are after is the evidence of the past, and a better documentation than has been retrieved from desiccated and eroded landscapes in the past century. In America and Europe such sites have occupied well over 90% of archaeologists’ time and over 95% of the funds and support for excavations even in the past decade. Doubtless the same tale is true for other regions of the world where wetlands exist. We seek today better data for the questions that remain unanswered after a century of dryland work and education in a dryland context. Through this, our expectations have been set so low that we can barely begin to grasp what is available to us with wetland survey and excavation. Our archaeological models are so fragmentary and skeletal that a gram of flesh and blood evidence may collapse them, and rightly so. Models used to explain the past must be suspect if they are based on fragmentary, desiccated, decayed, eroded, and ephemeral evidence of the kind that dry sites yield. What is needed is a reversal of the archaeological process, a time, all too short, to extract and retrieve new kinds of data, a time to create new models of the past, and a time to test current interpretations and to rethink the aims and possibilities for archaeology.

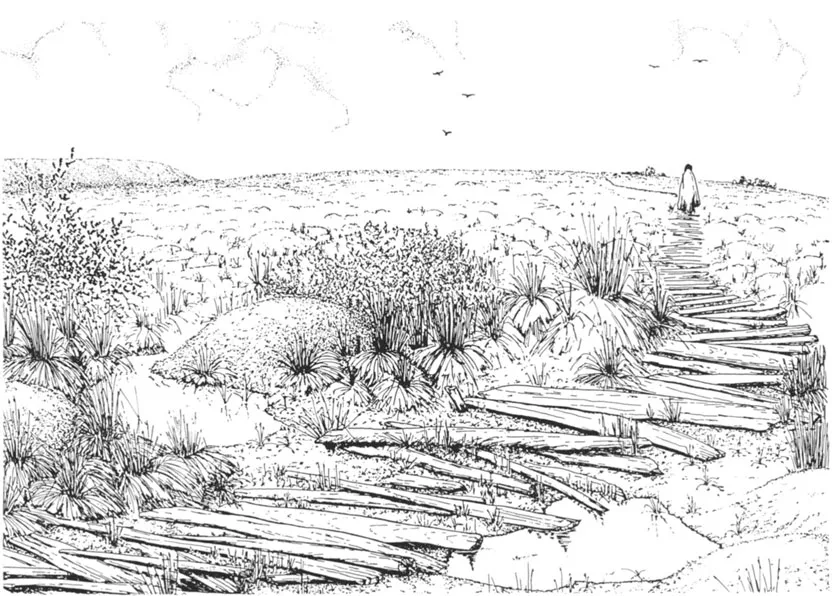

It is important to realize that there are various types of wetlands and that their ancient exploitation differed. Archaeological residues from these areas will also be of unequal quality and quantity. Some wetlands were used only for the gathering of wildlife, or were traversed by pathways leading into and out of the wet areas (Fig. 1). Others were exploited for crops, for animal grazing, or provided space for settlement and industry. Because wetlands are varied, were used differently, and have undergone unequal post-depositional processes, their archaeological contents will also be unstandardized. Some will be full of wood while others will astronish with their yield of materials of all kinds which were submerged in the wet deposits and sealed by peat, clay or silt. Protected from scavengers and from many of nature’s own erosional forces, the structures and other artifacts remain in conditions of survival only dreamed of when excavating dryland sites (Fig. 2). Some entire landscapes, where ancient settlements have survived by waterlogging and bog formation, can be identified by field reconnaissance using field-walking, aerial surveys, remote sensing, and sub-surface coring. This can yield remarkable information about settlement patterns.

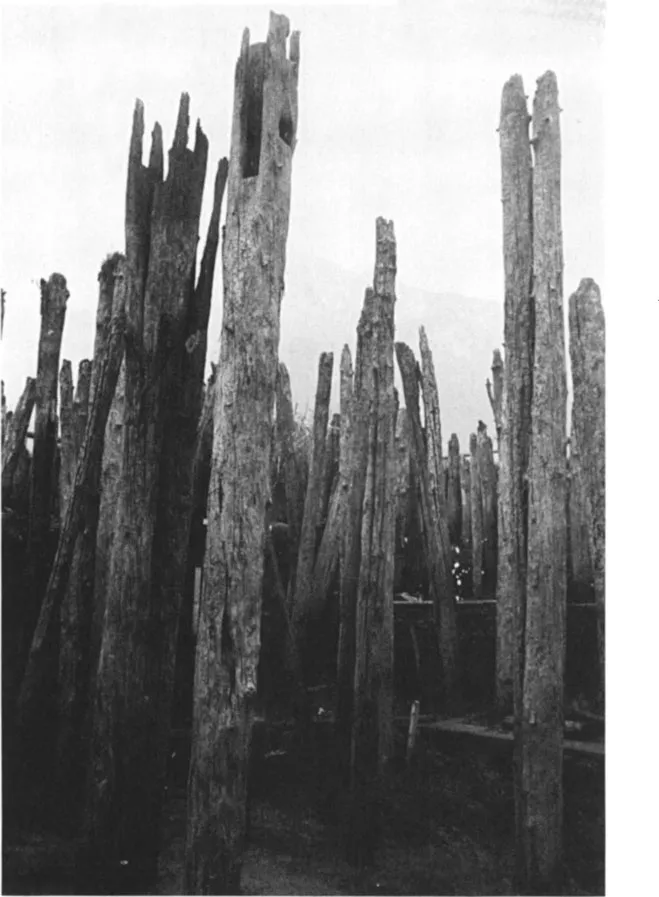

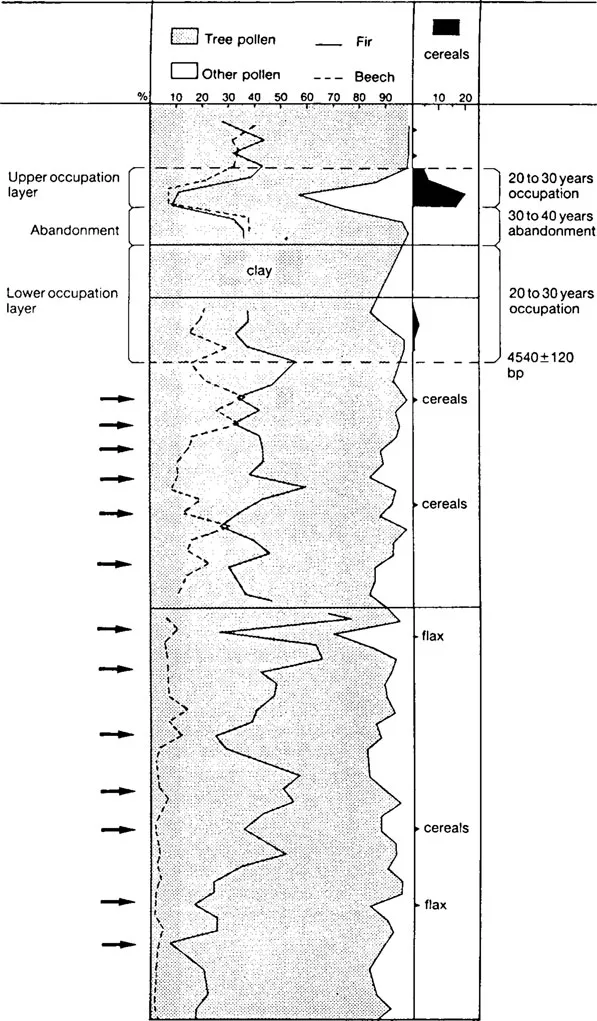

Wetlands of most types also yield immense quantities of environmental and economic data, including pollen and macroscopic plant remains of leaves, bark, and seeds; beetle, spider, and fly fragments; and larger animal remains and molluscs. Such an abundance of evidence can sometimes deter archaeologists and those who fund our work; however, without exploiting every opportunity, there is little point in arguing the case for wetland research. In addition, the results of detailed extractive and analytical work can be impressive because they are precise. Precision in environmental reconstruction, for example, allows us to picture extinct landscapes down to individual tussocks of grass, boggy pools of water, a teaming insect life, and a detail for our interest in human activities that is quite beyond the reach and comprehension of dryland mentalities. Precision in another wetland sense comes from the tree-ring dating of preserved wood, which can provide not only absolute time (without the imprecision of radiocarbon dating), but also refinements of seasonality and the life and repair of individual structures, virtually imposing a dynamism of behavior upon the archaeologist (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 1 Reconstruction of a prehistoric wetland exploited for wildlife, and traversed by wooden roadways. The preservation of a variety of environmental indicators allows a high degree of precision in this environmental reconstruction. By a combination of archaeological, pollen, macroplant, and beetle and bird pellet analyses, all of these wetland plants and pools, birds, and wooden structures, can be envisaged in precise detail. (Drawn by R. Walker.)

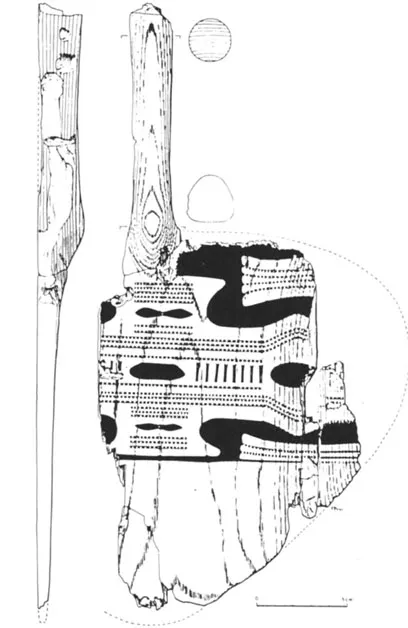

From time to time, wet sites also provide unexpected evidence that we could never have imagined existed—details about life and death, artistry and craftsmanship, and symbolism and ideology. Ethnographic and historic records assert that many societies do not create representations of their symbols of existence or their artistic achievements upon inert stone; rather they carve, engrave, weave and paint elements of their ideology on organic matter such as wood, textiles, and hides. These artifacts may survive in wet sites (Fig. 4) and, without such sites, we would be totally ignorant of many of these symbols of societies.

FIGURE 2 Part of the structural foundations and platform supports of the Bronze Age lakeside settlement at Fiavé, Lake Carera, Italy (cal 2000−1700) showing the extraordinary depth of preservation in a wet environment. (Perini 1984.)

It is not only ourselves that we must satisfy by our archaeological work. The public supports our endeavors, and in the long run it is the public who will determine the fate of our subject. Without question wet sites allow the public to gain a better appreciation of the past. These sites are often spectacular and better preserved than dry sites, and therefore are more understandable. We can see houses, palisades, cattle stalls, tools with handles, wagons, and sometimes the people themselves (see the article on bog bodies in this volume). Our reconstructions can be more accurate and more precise, and will therefore encourage the public to believe that archaeologists really do know what they are talking about, so long as they speak a comprehensible human language.

FIGURE 3 Pollen diagram of the Neolithic settlement Les Baigneurs at Charavines, France. The stratigraphy shown represents 600–700 years of sediments, with arrows indicating phases of deforestation of fir, some coinciding with episodes when cereals or flax were grown. The precision of chronological events from cal 3300 BC is based on dendrochronological analysis of the wooden structures. (Bocquet et al. 1987.)

FIGURE 4 Decoration imprinted and painted with ochre on a paddle of ash from the Tybrind Vig Mesolithic settlement,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Biographical Notes

- Preface

- 1 A Wetland Perspective

- 2 Problems and Responsibilities in the Excavation of Wet Sites

- 3 Recent Archaeological Discoveries in Lake Neuchatel, Switzerland: From the Paleolithic to the Middle Ages

- 4 The Peat Hag

- 5 The Location and Assessment of Underwater Archaeological Sites

- 6 New Applications of Remote Sensing: Geophysical Prospection for Underwater Archaeological Sites in Switzerland

- 7 The Somerset Levels: Multidisciplinary Investigations and a Wealth of Results

- 8 Wet Sites Archaeology at Red Bay, Labrador

- 9 A Waterlogged Site on Huahine Island, French Polynesia

- 10 The Significance of the 3000 B.P. Hoko River Waterlogged Fishing Camp in Our Understanding of Southern Northwest Coast Cultural Evolution

- 11 Research Design and Wet Site Archaeology in the Netherlands: An Example

- 12 Early Rainforest Archaeology in Southwestern South America: Research Context, Design and Data at Monte Verde

- 13 The Skeletons of Herculaneum, Italy

- 14 An Assembly of Death: Bog Bodies of Northern and Western Europe

- 15 Treatment of Waterlogged Wood

- 16 Marco’s Buried Treasure: Wetlands Archaeology and Adventure in Nineteenth Century Florida

- 17 Multidisciplinary Investigations at the Windover Site

- 18 Settlement, Subsistence and Environment: Aspects of Cultural Development Within the Wetlands of East-Central Florida

- 19 Environments of Florida in the Late Wisconsin and Holocene

- 20 Archaeological Wet Sites: Untapped Archives of Prehistoric Documents

- Index