![]()

1 Introduction: Sweden, Social Democracy and European integration

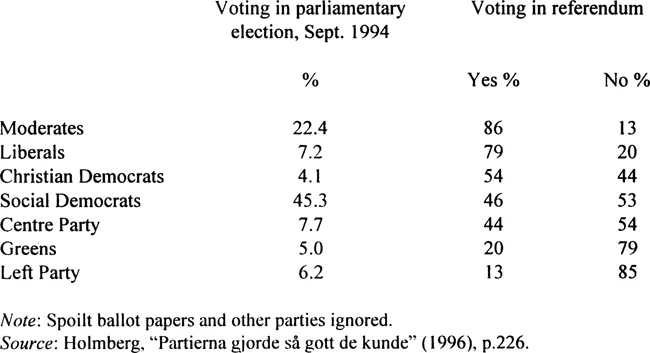

On November 13th 1994 Swedish voters decided in a referendum that their country should join the European Union, accepting the terms of accession agreed by their government eight months before. The referendum result was close, however: 52.2 per cent said Yes to Swedish membership, 46.9 per cent said No. The winning margin was just 295,000 votes. The issues of European integration and Sweden’s role in it had become highly divisive in the country’s political life. The fault lines in this division were and are varied, sometimes running parallel, sometimes cutting across each other. But they involved many of Sweden’s institutions, and perhaps none more so than its political parties. In some cases, it pitted them against each other. The Liberals and the conservative Moderates were fairly united in favour of membership, the Left and Green parties even more solidly against. But three, the Centre, the Christian Democratic and the Social Democratic parties, were badly divided over whether Sweden should or should not join the Union (see table 1.1). The Social Democratic Party {Socialdemokratiska Arbetarepartiet, SAP) is Sweden’s largest. It has won an average of 44.1 per cent in national elections since 1960, well over double that of the country’s second-biggest party, and was in government for a remarkable 60 of the 77 years up to 1998. The implications of the Social Democrats’ internal division are particularly far-reaching, for the party itself, for Sweden and, indeed, for the European left’s approach to the issue of economic and political integration. It is the subject of this study.

During the 20th century, much of it spent under Social Democratic rule, Sweden had established a glowing international reputation for the success of its economy, the humanity of its welfare policies and the righteousness of the international causes to which it committed itself. Indeed, left-leaning academics from elsewhere, notably in the English-speaking world, hailed the success of the so-called Swedish model. In 1989 a Cana dian, Henry Milner, described Sweden as “social democracy in practice”.1 An American academic, Tim Tilton, believed by the beginning of the 1990s that “it is clear that Sweden’s Social Democrats are not idly boasting when they claim to have built a social democracy.”2 Such admiration engendered among Swedes, particularly those sympathetic to SAP, a singular pride in their country. It was rich, highly civilised, and in world affairs it became something of a crusader for the rights of small countries. Its neutrality between the superpowers became increasingly activist as the cold war progressed, and Sweden’s leaders felt able to criticise America (over Vietnam, for instance) and the Soviet Union (over Afghanistan) equally. Indeed, Swedish nationalism evolved partly as a self-perceived contrast from the superpowers. Sweden was not big and impersonal, but small and accessible. It was not a dictatorship, but scrupulously democratic, with very high rates of popular electoral participation (average turnout in national elections since the war is an impressive 86.3 per cent). It was not imperialist, but anti-imperialist. It was in favour of free trade, yet its form of capitalism was not ruthless or cut-throat, but inclusive and egalitarian. Its women and ethnic minorities received very favourable treatment. Fundamental to this self-perception was the role of the Social Democrats. Their long years in government did much to foster the “welfare nationalism” that marked the Swedish character.

By the end of the 1980s, however, the pillars on which the success of the Swedish model rested had begun to crumble. The most obvious factor in this was the transformation of the international situation brought about by the collapse of communist rule in Central and Eastern Europe and the end of the cold war. To be sure, these events were as welcomed in Sweden as they were elsewhere. Yet for some European countries—the former communist ones, of course, but also others, such as Sweden’s Nordic neighbour, Finland—the demise of Soviet power offered almost nothing but new and attractive opportunities. “By contrast,” according to two commentators, “in Sweden, the end of the cold war era removed the supporting rather than the restraining structures of its identity as a nation state.”3 Finnish neutrality had been essentially a strategy for survival. Sweden, on the other hand, had exploited its neutrality to pursue foreign policy independently of the superpowers and their allies. As the relevance of neutrality diminished, Sweden’s special role in the world became less clear. After all, many asked who was there now to be neutral between? Even more debilitating was the steep decline of the Swedish economy. By the early 1990s the proportion of the workforce unemployed, long below 5 per cent, had risen to double figures. One political economist declared: “Though hardly extraordinary by comparative standards, these are staggering, almost unbelievable, numbers from a Swedish perspective.”4

Table 1.1 Party sympathy and voters'choice in Sweden's EU referendum, November 1994

A growing, high-employment economy had underpinned the Social Democrats’ remarkable electoral success, and created an image that had been sharpened by active neutrality in international affairs. By the 1990s the economy was in crisis and neutrality seemed irrelevant.

Sweden’s new situation was epitomised by the change in its relationship with the European Community. Since the EC’s inception in the 1950s, Swedes had grown used to standing outside it. Certainly, there were Swedes, mainly on the centre-right but also within SAP, who advocated their country’s accession from the beginning. But most had been more or less content, or at least resigned, to adhere to the official Swedish position that neutrality rendered impossible joining an organisation whose members were (until 1973) all also, through NATO, protagonists in the cold war. At the same time, among many in SAP there was a veiled sense of Sweden’s having little to gain or even to learn from the Community. During the 1960s some leading Social Democrats bluntly disdained the prospect of accession on the grounds that EC countries had “a more primitive social organisation than our own”.5 Though rarely stated so explicitly, SAP’s leaders had long sought to exploit politically the apparent superiority of the Swedish model; the country was contrasted with the raw, free-market capitalism and social conservatism that supposedly dominated political and economic life in the Community. Then, in the space of a few months in late 1990, a Social Democratic government changed its stance completely and announced its intention to apply for membership of the EC.

This study addresses two main research questions. First, why did SAP’s leadership change its policy towards the EU so abruptly? And, second, why was the party, whose unity and discipline had been such vital ingredients in its success during the 20th century, so divided by the leadership’s decision to do so?

Both questions demand an examination of the dynamics of making policy in a social democratic party, an appreciation of Swedish political circumstances and a position on the nature of European integration. They are also important to political science for a number of reasons. First and foremost, this study is of political parties and the ways in which they behave. To what extent is it a party’s ideology that determines its approach to a particular issue? Is its behaviour sociologically conditioned, in that the social location of its leaders, members and supporters sets parameters within which the party has to operate? Or are other, perhaps baser motives more influential? The party is, of course, an institution; and, like all institutions, it is ultimately composed of individual people. To what extent can party behaviour be explained in terms of the self-interest of these individuals? Is party behaviour a manifestation of a series of struggles, both within the party and with other parties, for the satisfaction of individuals’ desires and goals? Such questions have been the subject of voluminous academic debate. The case of Swedish Social Democracy’s trials with the issue of European integration, meanwhile, offers an excellent testing ground for competing theories of party behaviour. This is largely because our research questions identify real political puzzles. Why did SAP act as it did over Europe during the 1990s? Why has the party been so divided?

But our topic is also interesting for a number of more substantive political reasons. The response of parties to European integration raises questions about basic tenets of party politics in liberal democracies. Parties are often ascribed numerous functions by the literature dealing with them, in addition to perhaps their most important one, that of organising and constituting government. They structure the popular vote; they integrate and mobilise citizens; and they represent and aggregate different interests, coordinating the pursuit of both common and conflicting objectives.6 In short, they are vital mechanisms for maintaining linkage between governors and governed. The crisis of the party has been heralded at various times; such pronouncements have generally proved unfounded or premature.7 But European integration undoubtedly offers parties new challenges. How can meaningful linkage be maintained when binding political decisions are being made in the EU on the basis of intergovernmental negotiations? Accountability is a fundamental problem when the decisions to which national politicians contribute are the consequence of complex horse-trading with (at present) 14 other sets of politicians—not to mention assorted European commissioners and members of the European Parliament. On the other hand, it is questionable whether conventional parties could hope to construct in European institutions a new level of democratic accountability. Could parties ever reach across their national boundaries and present genuinely common policy platforms to a genuinely European electorate?8 Should they attempt it, parties’ ties to their national grassroots would surely be placed under great strain. The alternative, however, may be to live with a growing democratic deficit at the EU level.

Moreover, our topic is relevant to the development of European integration itself. For one thing, the large majority of the Union’s 15 member states currently have a social democratic party holding government office. The approaches that these parties take will obviously be a significant factor in determining how integration progresses. Second, SAP’s case, although striking, is by no means the only example of a major political party riven by differences over the European issue. As we shall see in the following chapter, other Nordic parties are similarly troubled by such divisions, and both Britain’s major parties have long been plagued by them. Most West European party systems were forged primarily by the contest for economic power and resources; when the advent of universal suffrage “froze” contemporary political configurations, it was this contest that formed the basis of the familiar left-right spectrum. Supranational integration, however, is very hard to fit into this spectrum. It offers something for (nearly) everyone: free trade and open markets for the right; resource redistribution and European-level reregulation for the left; handsome subsidies for agricultural interests; channels of cultural and political expression for national minorities. It is not obviously either a left-wing or a right-wing project, and so cannot be fitted neatly into existing party political cleavages. Thus, conflict over integration is as often found within parties as between them. Such internal division can cripple a party. If it is often in office, the implications for the governance of its country are clear.

These are dilemmas that face all parties, but they are perhaps especially acute for social democratic ones. They traditionally place great emphasis on, inter alia, two things. First, social democrats have been keen to use the power of the state for economic purposes—for which the institutions and public-policy instruments of the EU offer obvious possibilities. Second, they have stressed the need for effective, participatory democratic structures—for which the scale of European integration poses basic problems. It might be characterised as a conflict of politics against democracy.

The structure of the study

The rest of the book develops on the following lines. Chapter 2 places the case of Swedish Social Democracy in its political and research context. It briefly reviews some examples of West European social democratic parties that, despite initial scepticism, have come solidly to support further integration between the countries of the EU. A closer look, however, is warranted at SAP’s closest relations, its sister parties in Denmark and Norway, where, as in Sweden, integration has been the cause of considerable difficulty. Another brief review is then made of some of the theories of party behaviour, particularly those designed especially for application to social democratic parties, that may be of help in answering our research question.

Chapter 3 assesses the political conditions that SAP was facing from around the beginning of the 1990s. All political actors act within constraints—social, political, legal, historical, personal—and the Social Democratic leadership was certainly no different. Neutrality was for many years a political fact of life in Sweden, one that had great—although perhaps exaggerated—significance for any Swedish government’s European policy. The chapter further examines the ideological baggage that party elites were carrying, derived from decades of political success in the domestic arena. It addresses the notion of a “Swedish model”, a term often used vaguely in a wide variety of social and political contexts, but which here is applied to a particular theory of political economy that the two wings of the labour movement, the Social Democratic Party and the Confederation of Trade Unions (LO), developed between them. To be sure, this model had its successes. But the problems it was facing by the 1980s are, as will become clear, an essential ingredient in the arguments concerning European policy that are proffered in this study. Finally, it considers internal party structures. How free was the party leadership to pursue the European policies, indeed any policies, that it preferred?

Did the dispute represent a conflict of economic interest, or a fundamental clash of ideology? The presence of such fault lines would scarcely be surprising in a party so broadly based that it has occasionally succeeded in attracting support from over half the Swedish electorate. But their relevance for the divide over Europe can only be gauged through qualitative and quantitative research. The results of such research is presented in chapter 4. Chapter 5 then details the circumstances, both internal and external to the party, in which during 1990 a Social Democratic government dramatically changed Sweden’s policy towards the EC.

The following two chapters bring the study up to date. Chapter 6 recounts, given the existence of a split within SAP, the strategies adopted by its leaders to manage it and minimise the political damage that flowed from it. Analysis of these management strategies permits a judgment on whether they had the desired pacifying result, or whether in fact they may have inadvertently aggravated the party’s internal division. Chapter 7 then revisits the methodology used to analyse the party leadership’s volte-face over EC membership in 1990 and applies it to a more recent European dilemma, that concerning the realisation of economic and monetary union (EMU)—a single European c...