eBook - ePub

History of Burma

From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824 The Beginning of the English Conquest

- 418 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

History of Burma

From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824 The Beginning of the English Conquest

About this book

Originally published in 1983, this book explores the history of Burma, including chapters on Burma before 1044, The Kingdom of Pagan and the Shan Dominion. Burma's history had been little studied until recently, until the Burma Research Socety, founded in 1910, began to collect material of all kinds, and this book may be regarded therefore as one of the first-fruits. The book presents a mass of original work and incorporates the results of research up to the date of going to press; it offersa flood of light on the still many dark places of Burmese history and constitutes distinctly a step forward in our knowledge of the subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access History of Burma by G. E. Harvey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

BURMA BEFORE 1044

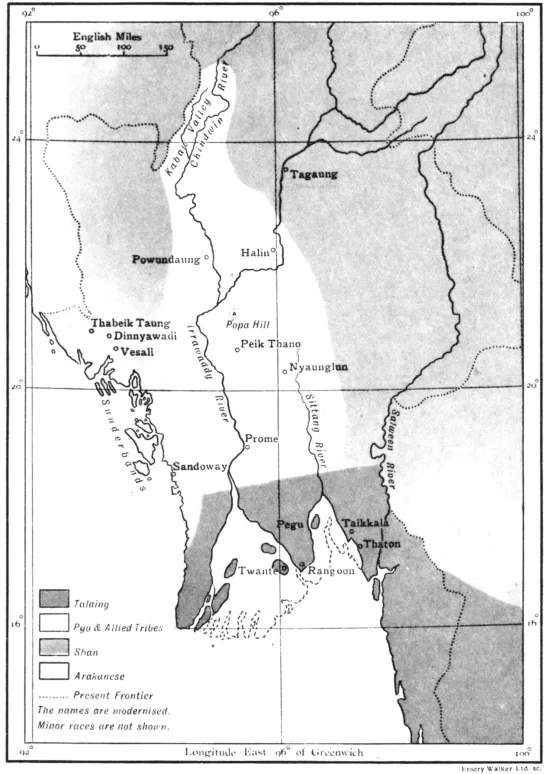

BURMA ABOUT 700 A.D. (Conjectural)

CHAPTER I

BURMA BEFORE 1044

BURMA,1 being little more than the valleys of a river system shut off from the outer world by hills and sea, is fitted to be the home of a unified people. But even now the process of unification, though accelerated, is incomplete; and when history began, the country was a medley of tribes.2

Perhaps the earliest inhabitants were Indonesians but they have left scarcely a trace and in any case they were displaced by Mongolian tribes whose home was probably in western China. These were the Mon and the Tibeto-Burman tribes from eastern Tibet. Doubtless they came down the great rivers, but the routes, order, and dates at which they came are purely conjectural. The Mon (Talaings) spread over Burma south of Henzada. The traditional names of the Tibeto-Burman tribes are Pyu, Kanran, and Thet; perhaps the Thet are the Chins, and the Kanran the Arakanese; the Pyu, now extinct, may be an ingredient in what afterwards became the Burmese, and they seem to have been pushed inland from the Delta coast by Talaing pressure from the south-east, as if the Talaing route into Burma was down the Salween. The Karens may have been earliest of all.

These races came, owing to causes such as drought and ethnic pressure, in successive infiltrations, each driving its predecessor farther south. Down from the north they came, tribe after tribe of hungry yellow men with the dust of the world’s end upon their feet, seeking food and warmth in tiny homesteads along the fertile river banks, seeking that place in the sun which has been the dream of the northern races in so many ages. The infiltration lasted centuries. The Shans did not enter the plains till the thirteenth century and the Kachins were penetrating Upper Burma when the English annexed it in 1885. Many of the immigrants must have been settled in before the Christian era. They lay thinly scattered over the country, illiterate animist tribes with little political organisation. Men dwelt in isolated units, divided by forest and hill, a scanty population whose hut-fires sent up smoke here and there above the jungle. The unit was doubtless the village, with communal tenures and rigid clan customs.1 If after a time kings came into existence they were little more than tribal chiefs

… in times long passed away,

When men might cross a kingdom in a day,

And kings remembered they should one day die,

And all folk dwelt in great simplicity.

We read of seven kings who went up to do battle against Taikkala (Ayetthima in Thaton district); but as their realms were all pressed in between the mouths of the Salween and Sittang rivers, each kingdom must have been no larger than a township.2

Indeed there can hardly have been political units of any size before writing came into use.3 Although it was not unknown before A.D. 500, no inscriptions of earlier date have yet been found. It was brought, probably about A.D. 300, from South India to the Pyus first of all, as part of the great Hindu expansion overseas; the earliest Pyu inscription contains Kadamba letters which were in use at that date near Goa on the Bombay coast. Hindus had come long before but it was not till this time that their cultural influence took root; they brought writing, customary law, and other elements of civilisation.1 They founded kingdoms in Java and Sumatra, and dotted the coast from Bengal to Borneo and Tonkin with little trading principalities such as Prome, Rangoon, and Thaton. Their coming was generally peaceful, for if they came as individual traders they would be welcomed; and if they came in numbers to set up independent communities, there was usually room in so thinly populated a land. But as time went on there was less room, at any rate in the places most worth having; and a few traditions such as the following suggest that at times there was petty fighting:—

THE STORY OF THE TALAING HERO KUN ATHA.

Thamala king of Pegu [A.D. 825–37] made his younger brother successor to the throne and, promising to welcome him on his return, sent him to learn wisdom from a famous teacher at Taxila. Now on the border between the realms of Pegu and Thaton there dwelt an aged Karen couple working their ya fields, and they had a daughter, and Thamala the king made her his chief queen. And the months and the years went by, and she conceived in her womb, and the king forgot his brother Wimala.

Now Wimala, having learned wisdom, bade farewell to his teacher, and returned home. But because his brother the king forgot his promise and welcomed him not, forthwith in anger he slew his brother the king. And inasmuch at that very time the queen gave birth to her son, he ordered that the new-born babe also be slain. But the queen, with grief in her heart, hid the babe outside the town near a pasture where buffaloes graze; and the nat fairies guarded him, and day by day he grew in wisdom and strength.

When he was sixteen years old, Hindu strangers came to the land. They were angered because the Talaings had driven them out, and they came back saying “We will fight and regain Hanthawaddy.” Led by Lamba, a giant seven cubits high, they came in their ships and surrounded Pegu town and sent a letter to Wimala the king. And when he had the letter, Wimala the king sent out messengers to seek a champion; but though the messengers searched, they found no champion.

Now at that time a certain hunter went hunting in the forest, and he came to where the wild buffaloes graze, and lo! among the buffaloes there stood a valiant youth. And the hunter returned home, and he told his wife, and she said “Husband, if this be true, tell it to the king, and he will reward thee.” And the hunter told the king, and Wimala the king sent ministers to fetch the youth. And when they brought him, at once Wimala the king knew him for his nephew, and he ennobled him and called his name Atha-kumma, because he should conquer his enemies. Then Wimala confessed his sin, and in that moment Atha-kumma plighted his troth to fight the Hindu strangers. But first he waited seven days, and sought the buffalo who was his foster-mother to ask her leave, and she gave him leave and shewed him how to fight and conquer. Then he returned to Pegu town and did battle there,1 and speared the Hindu giant in the side, and took prisoner seven ships and three thousand five hundred Hindu strangers. He built Kyaikatha [the pagoda of Atha, in Thaton district]. And Wimala the king made him successor to the throne. (Nanda-thara.)

The Burmese are a Mongolian race, yet their traditions, instead of harking back to China, refer to India. Their chronicles read as if they were descended from Buddha’s clansmen and lived in Upper India. Even their folk-lore is largely Hindu. Most of their towns have two names, one vernacular, the other classical Indian,2 just as the Latin Church made it the fashion for every city in Europe to have a Roman name whether the Romans had been there or not. A few of these classical names are due to actual immigration from the original namesake in India; thus Ussa, the old name for Pegu, is the same word as Orissa, and Pegu was colonised from Orissa. The surviving traditions of the Burmese are Indian because their own Mongolian traditions died out. The only classes who could read and write and keep traditions alive were their ruling class, the Indian immigrants.

In Upper Burma these immigrants came overland through Assam; in Lower Burma they came by sea from Madras. In some localities, such as Thaton, Prome, Pegu, Rangoon, and in many a town in Arakan, Indian immigrants doubtless formed a large proportion of the population; indeed the name “Talaing” is probably derived from Telingana, a region on the Madras coast whence so many of them came.3 Like good Hindus, they built little shrines; and it is probably these shrines that form the original strata of such pagodas as the Shwemawdaw at Pegu, the Shwedagon at Rangoon, and the Shwezayan at Thaton, all of which may well date back, in some shape or another, to before the Christian era. They brought their clergy with them, just as chetties and European merchants do now in Rangoon, and with as little result on the people at large. As a rule their religion was a domestic matter, but in the course of centuries they became so numerous as to effect peaceful penetration. Moreover, their Hinduism begun to include Buddhist elements after 261 B.C. when Asoka conquered the Kalinga and introduced Buddhism into South India. Its spread there doubtless took some time—the absorption of a religion is a slow process—and its spread to Lower Burma probably took longer still. What must have been a decisive factor was the rise, in the fifth century after Christ, of a great Hinayana centre at Conjeveram in Madras under the commentator Dhammapala; ancient Talaing writings frequently mention Dhammapala and Conjeveram, and the earliest Talaing inscription is in the Pallava alphabet used there in his time.

The faith existed side by side with Brahmanism. What the excavator1 finds in Burma is often Hindu rather than Buddhist. In some sculptures Buddha appears as an incarnation of Vishnu. The legend of Duttapaung,2 the Pyu chief, is tinged with Sivaism, for he is described as having three eyes; and what look like phallic emblems have been found at Pegu.

Doubtless these changes affected for the most part only the towns, the trade centres, and the rulers who, if not foreigners, intermarried with foreigners. The bulk of the people outside went on in their old quiet way worshipping stocks and stones—the usual animism and spirit worship of simple races. Religious strife is scarcely mentioned; but that there were occasional struggles between Hinduism and Buddhism is indicated by traditions such as

THE STORY OF THE TALAING HEROINE BHADRADEVI (TALAHTAW).

Tissa [A.D. 1043–57] was a heretic king [of Pegu]. He… made no obeisance to Buddha, to the Law he hearkened not, he honoured the Brahmans. He threw down the images of Buddha, he cast them away into ditches and marshes.

Now there was a certain merchant’s daughter who clung to true religion. Bhadradevi was this maiden’s name. From her tenth year up she went out to listen with her parents and she hearkened continually to the Law. She had exceeding great joy in the Three Gems. Daily she said the Three Names of Refuge with care. And it came to pass that the time when she was in her first youth was the time when the king cast down the images of Buddha. At that time the maiden went down to bathe, and by chance she thrust her hand against an image of Buddha. And she drew it up, and it glistened with gold. She asked “Who has caused this image to be cast away?” And the old slavewomen made answer “Lady, this king follows the word of false teachers. Verily it is the king who has caused this image of Buddha to be cast away. Whoever greets, honours, or bows before Buddha at the pagodas, him the king causes to be slain and to be brought to naught.” Thus said the slavewomen. When the maiden had heard their words, she spake on this wise “I obey the Three Gems. I can endure death. First wash the image clean, then set it up at a pagoda.” She herself and the slavewomen washed it and set it up at a pagoda.… Now as she was setting up the image, these things were told to the king. And he sent runners to call her. The maiden, that ring adorned with gems beyond price, spoke to the king’s runners saying “Let me abide here before the image.” And she made haste to wash every image of Buddha as many as were there, and to set them up, every one. And after a time the king sent more runners. When the maiden came before the king, she spake unto him. But he listened with anger, and spake in this wise “Take her to the elephants that they may trample her to death.” Then the maiden caused gentleness to soften the king and the elephants and the elephant-men, and continually she said the “I take refuge in the Lord” and she called on the Three Names of Refuge. And the elephant dared not tread on her, but he roared with his voice, neither could the elephant-men make him run at her. Many times they brought other elephants, but no elephant dared tread on her. So men told the king in fear. When the king heard these things, he spake in this wise “Cover her with straw for the funeral pyre.” But the maiden caused gentleness to work again, and she called on the Three Names of Refuge. Men stirred themselves to bum her, yet she burned not. So they told the king in fear. Thus spake the king “Bring her here.” They brought her to the king, and he said “O maiden! When I see the image of Buddha thy teacher fly up into heaven, then mayest thou live. But if from the image of thy teacher there fly not up seven images, eight images, I will have thee cut into seven pieces.” And he had her led to the foot of the ditch… and she prayed on this wise “O image of the Lord of Bliss! I thy handmaiden set up thy images. Buddha is lord everywhere, his Law is lord everywhere, his Church is lord everywh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- PREFACE

- AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- LIST OF MAPS

- CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

- CHAPTER I. BURMA BEFORE 1044

- CHAPTER II. THE KINGDOM OF PAGAN OR THE DYNASTY OF THE TEMPLE BUILDERS 1044-1287

- CHAPTER III. SHAN DOMINION 1287-1531

- CHAPTER IV. THE OVERSEAS DISCOVERIES

- CHAPTER V. ARAKAN

- CHAPTER VI. THE TOUNGOO DYNASTY 1531-1752

- CHAPTER VII. THE ALAUNGPAYA DYNASTY 1752-1824

- NOTES

- GENEALOGICAL TABLES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX