eBook - ePub

Deep Stall

The Turbulent Story of Boeing Commercial Airplanes

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Deep Stall applies a framework of strategic analysis to the Boeing Company. Boeing is the world's largest aerospace / defence company, with turnover in the region of US $60bn. The book examines the relative decline of Boeing in the civil aircraft market in relation to European manufacturer, Airbus. The aim of the book is to utilize the concept of strategic value to explain Boeing's decline. The authors define this concept as investment in people and technology to leverage future market success by developing innovative new products, arguing that Boeing has neglected strategic value in favour of shareholder value, defined in terms of short-term cash benefits. The rationale for the book exists both in the fact that the story in itself is interesting and also in the wider framework of analysis concerning the correct strategic approach for running a high technology business. The argument illustrates what can happen when quarterly returns become the predominant strategic rationale for a company. In the U.S. the business media (Economist, Forbes, Fortune, and Business Week etc) are now focusing on the question of Boeing's decline and the major implications for the U.S. national interest. Boeing is one of the jewels in the US technology crown, but today U.S. jobs and capability are being exported abroad, with most of its aircraft program work based in Asia. This is a hot topic in the US which explains why the business media are now so interested in this question. The book sits squarely in the centre of this debate. Deep Stall concludes with a brief analysis of the recent fight-back that has been evident in Boeing's fortunes and the successful campaign to sell the new 787. The authors probe the question of whether Airbus or Boeing is likely to dominate in the next ten or fifteen years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Deep Stall by Philip K. Lawrence,David W. Thornton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Pre-History: The Era Before Civil Jet Transport

Introduction

In the lead up to the centenary of the Wright brothers' first successful flight, North Carolina and Ohio engaged in a running dispute over which state had the right to make public claims as being the location most responsible for the genesis of powered flight. The arguments of both have merit, in that the Wright brothers did important work in both Dayton and Kill Devil Hills; the machines were built in their Ohio shop, but assembled and tested on the windy dunes of the Outer Banks. But in reality the geographical net should be spread more widely. Their achievement of 17 December 1903, the first sustained and propelled flight, was the result of theoretical insight and practical skill, in conjunction with a real willingness to risk life and limb, which drew on the insights, successes and failures of countless others on both sides of the Atlantic, (Solberg, 1979, ch.1). To emphasize the European connection it should also be noted that the Wright brothers obtained their first patent from France and opened their first training school in Paris.

Ironically, the success of 1903 was not followed by instant celebrity, and only a few Americans (and even fewer Europeans) knew of or believed in what the Wright brothers had actually accomplished. It was not until 1909, after successful demonstrations of their flying machine for the US War Department, and similar demonstrations in Europe, that the significance of their achievement was appreciated by the public or by governments, (Bilstein, 1994, pp. 1-11). Glen Curtiss was perhaps better known, having made his start in aviation in 1904, after landing a US Army contract to construct an engine for a dirigible. Along with Alexander Graham Bell, in 1907 Curtiss formed the Aerial Experimentation Association and by 1910 was astounding the nation by flying the 'June Bug' 150 miles from Albany to New York City, with only a single stopover at Poughkeepsie, (Solberg, 1979, p. 8).

Aeronautics and the State

With the sudden growth in public enthusiasm for planes and their pilots, air shows and other demonstrations (all dangerous and many fatal for pilots and spectators alike) were the main uses of early aircraft. But both entrepreneurs and governments recognized that other purposes might be served, with short-range passenger services and experimental mail flights beginning at nearly the same time. Predictably, numerous firms designing and manufacturing planes sprung up, and although investors duly took note the predicted big aviation boom failed to materialize. Indeed, despite the early American successes in aviation, many in US government and industry believed that the United States had begun to fall behind in comparison to European aeronautics. A fact-finding mission organized by the Smithsonian Institution was sent to Europe to investigate developments in Europe, headed by Albert F. Zahm of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His report, issued in 1914, led directly to the creation in 1915 of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), whose mission was to conduct basic research on aeronautical topics with both civil and military application, (Bilstein, 1994, p. 31). Thus, only a dozen years after the Wright Brother's first flight, the United States government had begun to take a deep and abiding interest in aeronautics.

In 1909 the Frenchman Louis Bleriot flew across the English Channel, and the age of powered flight had begun in earnest. It should come as no surprise that this elemental feature of aeronautics would emerge originally in the European context, the fount of the very idea and practice of the state and also the starting place of the two World Wars. The title of Anthony Sampson's insightful history of the world airline industry, Empires of the Sky, is particularly apt because it captures in so few words the essential nature of the development of the early aeronautics industry. Often depicted as the achievement of individual heroes, such as the Wright brothers, Bleriot, and Lindbergh, human mastery of the air also has been very much a triumph of governments. To an important degree the entire business of making and flying aircraft, most especially its key economic and technological features, is the concrete manifestation of state priorities. Foremost among these priorities has been self-preservation; it is no accident that the most significant advances in powered flight have been made during wars both hot and cold. If necessity is the mother of invention, then modern aeronautics is the offspring of intense interstate rivalry and conflict: 'In every country the soaring ambitions of the aviators and their financiers came up against the controls and military designs of their governments', (Sampson, 1984, p. 24).

With the advent of powered flight at the turn of the century, European governments felt a pressing need to create a set of rules to regulate the new possibility of regular air transit across international boundaries. With French engineers and pilots playing a leading role in the nascent field of aeronautics (the Wright Brothers notwithstanding), it was appropriate that the first international convention on air navigation convene in Paris in 1910, the first intergovernmental meeting of its kind. While accomplishing important definitional and technical tasks relating to transnational air travel, delegates differed sharply on the central issue at hand, sovereignty; the right of states to control the airspace above their territory. They adjourned agreeing to disagree on this key issue, showing that aviation could never be divorced from its political implications.

Boeing and the Emergence of US Aviation Policy

Eugene Rodgers notes that William Boeing had his first experience with flight on 4 July 1914, as he and Conrad Westervelt paid for repeated holiday rides over Lake Washington on a barnstormer's aircraft, (1996, p. 24). The two subsequently bought a seaplane and took flying lessons from Glenn Martin to pursue their new hobby. As the First World War spread across Europe and threatened to involve the US, Boeing and Westervelt came to view airplanes and the ability to build them as crucial to the country's security. Leading promoters of aviation in the Pacific Northwest, the two entrepreneurs began work on a plane to be built from the spruce wood, which was so abundant in the region and designated it the B&W. Although Westervelt was called back East for military service, a determined Boeing drew on his personal wealth to form the Pacific Aero Products Company, and the plane's first test flight took place on 16 June 1916: 'He was clearly getting in on the ground floor: In the whole country, only about four hundred aircraft were built in 1916', (Rodgers, p. 29).

Disappointed in finding no civilian customers for the B&Ws, Boeing brought in engineers to modify the design, and in 1917 convinced the Navy of the virtues of his Model C prototype, winning a contract worth $575,000 for 50 trainer aircraft. Reincorporated as the Boeing Airplane Company, 'the good news put the infant company in business for keeps', (Rodgers, p. 31). More navy business followed as Boeing was contracted to build 50 flying boats on license from Curtiss, work that dovetailed nicely with Boeing's shipbuilding experience. But such heavy reliance on military contracts made the company vulnerable to political developments, with both labour and management subject to the vagaries of procurement decisions. As Rodgers puts it: 'November 11 1918. was a great day for the bloodied world but a bad day for Boeing's business: The Great War in Europe ended', (Rodgers. p. 32). The flying boat order was immediately cut in half, and the layoff of half the workforce quickly followed, as the company unsuccessfully sought to diversify into wood products.

At the dawn of the aviation era, the US was less concerned about supporting the nascent industry than its European neighbours. Perhaps unfairly, the US aviation industry had emerged from the First World War publicly discredited and without a clear sense of mission or future direction. Although the NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) had been formed in 1915 to undertake research basic to all aspects of aviation and flight, its mission became more militarily oriented as time passed, and its budget remained small. Recognizing the dangers posed by the rapid post-war contraction of military orders, the industry sought to increase public and governmental awareness of the importance of its products, primarily through the Manufacturers Aircraft Association set up during the war to coordinate production. Its chairman Samuel Stewart Bradley, accompanied a delegation to Great Britain led by Assistant Secretary of War, Benedict Crowell (the Crowell Commission) in the summer of 1919 and came back convinced of the necessity for the United States (like every industrial nation) to maintain a viable capacity in aviation both civil and military. But the time was not yet ripe for an active US government role in aviation. As Nick Komons notes, 'legislators appeared more interested in dredging up the shortcomings of wartime aircraft production than in establishing the relationship between the Federal Government and civil aviation', (Komons, 1989, p. 43).

Throughout the 'dark years' for the US aviation industry following the First World War, Samuel Bradley (also head of the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce formed in January 1922) and others, such as General William 'Billy' Mitchell, stressed the need for the government to finance and manage a revitalization of both the military and commercial sides of the industry, (Komons, 1989, pp. 70-79). Entrepreneurs such as Bill Boeing were in dire need of such help from government. Boeing even put his fledgling enterprise up for sale, but found no takers, losing $300,000 in 1920. But in a move which foreshadowed the future, the company was rescued by government orders for aircraft. In 1921 the Army sought bids for the production of 200 support planes. Boeing won the competition to build them by underbidding even the designer of the plane, Thomas Morse, and then proceeded to make a profit on its manufacture. In the fledgling industry Boeing emerged as the leading supplier of military aircraft, (Rodgers, 1996, p. 35).

A US Strategic Industry

Eventually, industry lobbying in the US began to pay dividends. The efforts of Bradley were finally rewarded as the Morrow Board (appointed by President Coolidge) advised Congress in its report of 30 November 1925 to act in the overseeing of the emerging sector so as to instill public confidence. The result was the Air Commerce Act of 1926. the purpose of which was to regulate and rationalize the airfreight business, give the federal government powers in regulating the safety and licensing of aircraft and pilots, and accompanying five-year procurement plans for both the army and navy. With the act. aviation was thus recognized explicitly as a strategic industry in the United States, (Komons. 1989, p. 88). But the legislation also intended for the Department of Commerce, through its newly-created Aeronautics Branch, to promote the growth of commercial aviation, and in so doing, 'the framers of the Air Commerce Act. by entrusting to a single agency both promotional and regulatory powers, had created a potential and permanent source of conflict', (Komons, 1989, p. 92). Under the direction of the Aeronautics Branch the federal government was also the driving force behind the creation and maintenance of a network of radio communications and weather information distribution that served as the foundation for subsequent commercial development in aviation.

The Role of Air Mail

Perhaps the most important measure of government help to US commercial aviation had come with the inauguration of air mail service in 1918, which had been followed by the Air Mail Act of 1925 (the Kelly Act) that allowed the awarding of contracts to private concerns for mail delivery, (Komons. p. 66). The economic viability of the new service depended, not only on a network of ground-based navigation capabilities, but also on night flying, and entailed the construction by the Post Office of a network of lighted airways across the country. By so doing, the national government was performing a crucial economic and commercial function relative to the nascent aviation sector: 'In developing its air mail routes, the Post Office, though operating as an arm of the government, was playing the classic role of entrepreneur', (Heppenheimer, 1995, p. 11). Indeed, without its new key role in the service of government, it is doubtful that the industry could have justified its commercial existence:

Airmail was the only significant civilian application of aircraft. By establishing airfields and installing navigational beacons along its routes ... the Post Office had begun to establish an infrastructure that would allow commercial aviation to expand. Congress hoped to speed up development of passenger and freight service by providing a large, steady airmail business for private airlines, (Rodgers, 1996, p. 36).

There was also federal assistance in the technical sphere. Government support in the form of a wind tunnel built in 1928 by the NACA led to additional and significant technical progress in aircraft design. Used to test the aerodynamic effects of cowling engines by installing them within the wing structure 011 a aluminum monoplane airframe to reduce drag, 'these developments now offered far-reaching opportunity to design and build a new generation of aircraft that would offer unprecedented speed and performance', (Heppenheimer, 1995, p. 44).

Figure 1.1 Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974)

The solo flight of Charles Lindbergh from New York to Paris in 1927 did more than any single previous event to stimulate public interest in flight and the aviation industry in the United States. His accomplishment created the so-called Lindbergh boom; an explosion of public interest and investment in aviation projects and the firms undertaking them. (Solberg, 1979, p. 73). Lindbergh's popularity provided the public support necessary to allow federal funding of airport construction across the country, in Komons view: 'perhaps the most important promotional activity undertaken by the Aeronautics Branch', (1989, p. 173). The massive influx of capital initiated a period of rapid consolidation and vertical integration within the US aviation industry, with four firms emerging to control virtually all aspects of aircraft production and air travel.

Boeing’s Consolidation

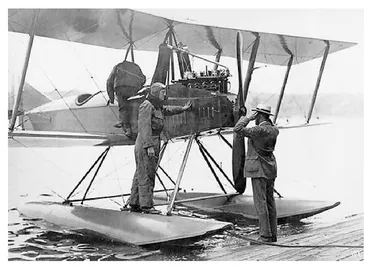

The Boeing Company already played a small but significant part in the development of air mail service, flying a batch of mail from Vancouver to Seattle, the first air mail service between the US and Canada. On 3 March 1919. William Boeing and pilot Eddie Hubbard carried the first US international air mail in the Boeing Model C pictured below.

Figure 1.2 Bill Boeing (right) and Eddie Hubbard with a Boeing Model C Credit: BoeingImages.com

In 1926, two of the company's key employees convinced Bill Boeing to take a substantial risk of his personal capital by building 25 planes to carry the mail and a few passengers along the Chicago-San Francisco segment of the trunk mail routes put up by Congress for bids, (Rodgers, 1996, p. 38). Having won the contract, the Model 40A aircraft would be operated by a new subsidiary incorporated on 17 February 1927 as Boeing Transport Company, carrying not only mail, but a few passengers as well. Involved in both manufacturing aircraft and operating them for commercial purposes. Boeing was now well positioned to respond to the 'Lindbergh boom' in air travel. Taking advantage of investor interest in aviation firms. Bill Boeing listed his company on the New York Stock Exchange on 1 November 1928. He then moved quickly to solidify his market position by merging his holdings with Pratt and Whitney, the Connecticut-based engine manufacturer, creating the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation (UATC) on 1 February 1929. Aggressively pursuing the acquisition of smaller manufacturing concerns and airlines alike. UATC emerged as the country's dominant aeronautics firm by the early 1930s, and Bill Boeing and his partners became millionaires, (the airlines acquired were combined to form United Airlines).

Air Mail Subsidies

The position of Boeing and its counterparts was strengthened further in 1930 when the largest three conglomerates were awarded all but two of the 20 contracts for air mail delivery in the United States. According to Nick Komons, these 'government air mail contracts were in fact lucrative subsidies for carriers', (1989, p. 191). The Air Mail Act of 1930 (McNary-Watres Act) permitted the Postmaster General to grant air mail contracts without competitive bidding, broad powers were adopted, not only to consolidate air mail service but also to encourage mergers among airlines and thus rationalize the industry. By cutting mail rates and paying carriers according to space available, the US government also stimulated the airlines to seek passenger traffic for additional revenue. In so doing the airlines were given a strong spur to technological innovation, as passengers' demands for increased speed and comfort encouraged a wave of innovation in airframe and engine design (Heppenheimer, 1995, p. 36). Thus. 'By means of this sudden transformation of scale, an industrial base was formed that for the first time put American aviation on an equal footing with European' (Irving, 1993, pp. 31-32).

With the aid of government support and despite the damage done to almost every other sector by the Great Depression, by the early 1930s the aviation conglomerates had become a formidable oligopoly in an industry experiencing rapid structural and technological change. The new economic environment created by the Postal Service, combined with technological changes dr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Pre-History: The Era Before Civil Jet Transport

- 2 Boeing and the Cold War: From the Jet Bomber to the Civil Transport

- 3 Extending the Product Range: From Financial Disaster to Market Dominance

- 4 European Renaissance: The Rise of Airbus

- 5 Boeing's Response to the A300: A Tale of Two Models

- 6 Boeing: The Flight from Innovation

- 7 Interlude: The Airbus vs. Boeing Trans-Atlantic Trade and Subsidy Battle

- 8 The Crisis Deepens

- 9 Postscript: A Boeing Comeback?

- Bibliography

- Index