In this essay, I shall explore studies of the voice in psychoanalysis and music. I will look at essays and books that theorize the voice, and I will explore some limited analytical applications. These writings have been widely influential in shaping contemporary critical discourses. The essay is organized through a roughly chronological series of mostly twentieth-century writings with examples of music from across classical periods, and styles. The main purpose of the essay is to give readers who are familiar with current critical theory (psychoanalysis, theories of the voice) a resource comprising both a survey of theories of the voice as well as illustrations of how these theories can be applied primarily to musical-theoretical but also musical-historical criticism. A secondary purpose of the essay is to give readers who may be exploring theories of the voice and psychoanalysis for the first time a resource for exploring writings on the voice as a context with which to understand the various uses and misuses of the voice in traditional as well as contemporary classical musics.

While exploring the voice in the readings, I will locate each approach within its disciplinary and critical context, suggesting to the reader various paths of inquiry that can lead into a deeper understanding of the writings at hand, the musical examples cited, and their cultural contexts. Three red threads of discursive continuity run throughout this survey of theories of the voice: (1) the voice as a vehicle for the communication of meaning, (2) the voice as vehicle for the communication and/or expression of an aesthetic nature or emotion, and/or (3) the voice as object (of some sort) in and of itself. I shall also explore vocal signification and the body.1

Roland Barthes, ‘The Grain of the Voice’

Roland Barthes’ essay ‘The Grain of the Voice’ relies on an opposition of phenosong and genosong.2 Barthes acknowledges (though without direct citation) that he has borrowed the terms from Julia Kristeva. I shall explore Barthes’ essay by first looking at Kristeva’s use of the terms phenotext and genotext in some detail and then proceed with Barthes’ rereading of Kristeva and his application of his rereading to specific musical practices. Kristeva discusses the genotext as follows:

What we shall call a genotext will include semiotic processes but also the advent of the symbolic. The former includes drives, their disposition and their division of the body, plus the ecological and social system surrounding the body, such as objects and pre-Oedipal relations with parents. The latter encompasses the emergence of object and subject, and the constitution of nuclei of meaning involving categories: semantic and categorial fields. Designating the genotext in a text requires pointing out the transfers of drive energy that can be detected in phonematic devices (such as the accumulation and repetition of phonemes or rhyme) and melodic devices (such as intonation or rhythm), in the way semantic and categorial fields are set out in syntactic and logical features, or in the economy of mimesis (fantasy, the deferment of denotation, narrative, etc.). The genotext is thus the only transfer of drive energies that organizes a space in which the subject is not yet a split unity that will become blurred, giving rise to the symbolic.3

Kristeva is thinking of the genotext as an attribute of, or entity contained within, the phenotext. She sees the genotext in close relation or proximity to the body, to subjectivity anterior to the split that constitutes the divided subject since Freud. Further, she views the genotext as articulation of threshold precisely at that fissure that will give way to psychic split. For her, the genotext is ‘a process, which tends to articulate structures that are ephemeral (unstable, threatened by drive charges, “quanta”, rather than “marks”) and non-signifying (devices that do not have a double articulation)’.4

For Kristeva,

[w]e shall use the term phenotext to denote language that serves to communicate, which linguistics describes in terms of “competence” and “performance”. The phenotext is constantly split up and divided, and is irreducible to the semiotic process that works through the genotext. The phenotext is a structure (which can be generated, in generative grammar’s sense); it obeys rules of communication and presupposes a subject of enunciation and an addressee.5

For her, the split of the subject into primary and secondary processes and the subject’s full acquisition of language enable phenotextual articulation. The phenotext is constitutionally structured according to mutually exclusive binary oppositions of basic materials that undergo rules of transformation to become manifest texts—articulations to be shared among subjects in social space. For Kristeva,

[t]he signifying process therefore includes both the genotext and the phenotext; indeed it could not do otherwise. For it is in language that all signifying operations are realized (even when linguistic material is not used), and it is on the basis of language that a theoretical approach may attempt to perceive that operation.6

For Kristeva, the phenotext contains the genotext, and the boundary between them blurs and thickens as attributes of the latter become subordinate to the former.

When Barthes adopts Kristeva’s terms to music, he substitutes “song” for “text” and transforms Kristeva’s binary (in which a fluid boundary separates genotext and phenotext) into a more distinct binary opposition. Barthes is interested not so much in making a general, theoretical statement or category, as in explicating a personal source of pleasure. For him,

The pheno-song […] covers all the phenomena, all the features which belong to the structure of the language being sung, the rules of the genre, the coded form of the melisma, the composer’s idiolect, the style of the interpretation: in short, everything in the performance which is in the service of communication, representation, expression, everything which is customary to talk about, which forms the tissue of cultural values […] which takes its bearing directly on the ideological alibis of a period [….]7

Barthes does not directly address the plethora of issues that arise when one discusses articulation, meaning, and expression in music. He jumps simply to a discussion of song. He discusses phenosong in terms of the language element inherent in song as well as conventional elements of music other than the linguistic.

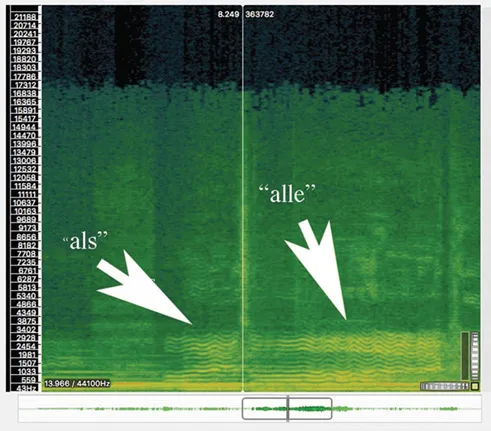

For Barthes, the quintessential vocalist of the phenosong is Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau, in whose singing Barthes ‘only […] hear[s] the lungs, never the tongue, the glottis, the teeth, the mucous membranes, the nose’.8 Barthes prefers musical performances in which the stain of the body not only remains but resonates openly. Rather than discuss such performances as geno-song, his language veers to the notion of “grain”: ‘The “grain” is the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs’.9 For Barthes, the quintessential vocalist of the geno-song is Charles Panzera. It can be difficult to follow claims such as Barthes’ in analysis; writers may find recently developed software helpful for visualizing acoustic data that goes beyond pitch-specific notations of conventional notation. Screenshots of minute excerpts will illustrate how such software may be used. In Figure 1.1, I reproduce a sonogram of a recording of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau performing “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” from Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe; the passage shows Fisher-Dieskau’s articulation of the words “als alle” from the beginning of the work whose first line is “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai als alle Knospen sprangen”.10

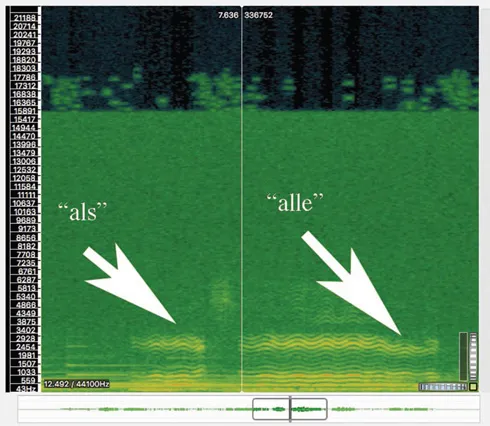

In Sonic Visualizer, frequencies measured in Hz are in white font against black background arranged vertically on the left; sung language is generally visual in the low 1000s, as here. One reads the image left to right, reflecting conventional representations of the passage of time. Dynamic level (how loud the signal is) is measured in colors on the spectrogram; from loud to soft, the colors move from red (rather loud) to orange, to yellow, to green (silent). You can see aspects of Fischer-Dieskau’s performance of the words “als alle” through his even and controlled vibrato. Notice the neat “stacks” of waves; these waves show the control of Fischer-Dieskau’s vocal production throughout the core of the notes he is singing; and looking horizontally, notice the clean “cutoff” after “alle”. See Figure 1.2 for a sonogram of a performance of the precisely same excerpt from the same song:11

Figure 1.1 Robert Schumann, “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” from Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe. Dietrich-Fischer Dieskau and Gerald Moore.

At the end of Panzera’s articulation of “alle”, there’s a sudden “hole” in the vocal production; notice the dug out portion of the yellow wedge as the point of the diagram’s arrow. This “hole” corresponds in the recording to a guttural articulation. I think Barthes would view these two screen-shots of sonograms from recordings as visualizations of his opposition of the phenosong (Fischer-Dieskau) and genosong (Panzera). Sonogram comparisons of the entire song show a plethora of other examples of this nature. Visualizations (as all musical examples) can cause one to continue to probe analytic claims. For example, one might notice that Panzera’s articulations of the words “als” and “alle” are cleaner than Fischer-Dieskau’s—cleaner in the sense that their beginnings and endings show more clearly marked thresholds. Such matters can be used to show differences in pheno-/geno-performances of any musician, playing any instrument.12

Figure 1.2 Robert Schumann, “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” from Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe. Charles Panzera and Alfret Cortot.

Barthes’ reading of Kristeva results in a simpler binary opposition, one in which singing in ...