![]()

Chapter 1

The Relationship Between Schistosomiasis Transmission and Human and Natural Environments

The disease schistosomiasis, its human health impacts, and measures to control it will be described in this chapter. The relationship between schistosomiasis transmission and the environment, especially through human contact with water, will be explored by using examples drawn from the developing world. The level of concern for schistosomiasis will be discussed, and mechanisms for limiting its increased transmission will be suggested.

The Life Cycle of the Schistosome

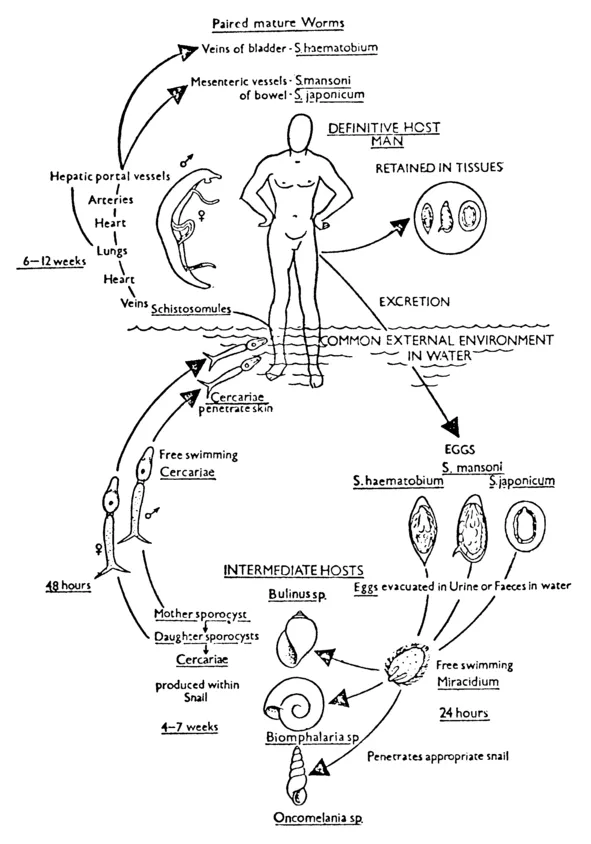

Schistosomiasis is transmitted by the schistosome, a parasitic worm of the trematode class. Three major species of schistosomes infect humans--Schistosoma haematobium, S. japonicum, and S. mansoni. S. haematobium worms live within the capillaries on the wall of the human bladder, and the other two species inhabit the blood vessels of the human large intestine. The separate male and female worms must mate for reproduction. Once mating has occurred, the male lays eggs in the vessels of the bladder or the large intestine and the eggs then pass through the tissues into the lumen of the bladder or intestine, eventually traveling out of the body via urine or feces.

At this point in the cycle water begins to play a crucial role

Figure 1-1. The life cycle of schistosomiasis. Source: John Homans, A Textbook of Surgery (6 ed., Springfield, I11., Charles C Thomas Publishers, 1945), p. 7. Courtesy of Charles C Thomas, Publishers, Springfield, Illinois.

(figure 1-1), since the eggs must reach water in order to hatch. Once in the water, which may be flowing or stagnant, the eggs hatch into miracidia, the first free-swimming larvae which infect snails, the intermediate host of the schistosomes. (As shown in figure 1-1, each worm species has its own particular snail host.) The miracidia must find the appropriate snail host within one day or die.1

Once inside the snail, the miracidia undergo asexual reproduction. A snail inhabited by a single miracidium can expel up to several thousand cercariae, the second free-swimming larvae of schistosomes. Cercariae emerging from the same snail are the same sex as the original miracidium, although snails may be infected by many miracidia and thus shed cercariae of both sexes. It is this second larval stage which infects man.

For the cycle to be complete, a person must be exposed to both male and female cercariae, Any part of the skin may be penetrated and, in addition, the length of time that the skin is exposed to water may influence the likelihood of infection. Inside the human body, the worms, now called schistosomules, migrate through the tissues to the circulatory system within which they are transported, via the heart, lungs, and liver (where mating takes place), to the bladder or intestine.2

This is a simplified view of the parasite's life cycle and its effect on humans. Complications from environmental conditions, snail host-parasite strains, and the physiological state of the human host may affect the parasite's penetration of snails and human host as well as its migration within the human host. The nutritional and health status of the human host may be important, at least in terms of disease consequences. Furthermore, some humans may become immune as a result of previous exposure to the parasite.3

Animals are also infected by S. mansoni and S. japonicum. These organisms, particularly S. japonicum, may prevent effective implementation of control programs because the animal hosts--cows, sheep, goats, and baboons--can act as reservoirs for human infections by transmitting schistosome eggs to the snails and thus contribute to transmission.

Public Health Considerations

Humans infected by schistosomes may not exhibit any clinical disease. Although it is estimated that more than 200 million persons in the world are infected, it is difficult to estimate the number who will suffer serious disease consequences. The infection, especially in chronic cases, usually causes weakness, anemia, bloody urine or stools, diarrhea, and painful micturation. These are generally debilitating, but not fatal, effects. Recent studies, however, show serious physiological impacts among the Sudanese, whose blood hemoglobin levels have been reduced to such an extent that oxygen flow to the muscles and brain is limited.4 This has resulted in impaired physical productivity. In addition, severe complications such as cirrhosis of the liver, cancer of the bladder, and central nervous system disorders may occur in humans affected with high worm loads, especially in those persons newly and frequently exposed to schistosomes who have not yet acquired immunity.5

Estimates of how many persons are severely affected by the disease require careful longitudinal studies. Too few such studies have been carried out, but reports have indicated that "up to 12 percent of the people autopsied after dying in hospitals in parts of South America died of the consequences of schistosomiasis. In parts of Tanzania around 20 percent of people have what in Western countries would be considered serious damage to the urinary tract and a proportion of these would be expected to live only a few years. These changes, in Tanzania, Zanzibar, Nigeria and Egypt, are seen commonly in children and would be expected to produce their most serious results in adolescent and early adult life."6

An earlier study of S. japonicum cases occurring in the Philippines classified the different stages of the disease:

Class I. Mild: Occasional abdominal pain, occasional diarrhoea or dysentery; no absence from work.

Class II. Moderate: anaemia (haemoglobin less than 10 gm per 100 ml, as recorded by the Haden-Hausser haemoglobinometer) or weakness; reduced capacity for work.

Class III. Severe: recurring attacks of diarrhoea and dysentery; frequent absence from work.

Class IV. Very Severe: ascites and emaciation; total absence from work.

A clinical gradient in the sample (of 278 persons) was established as 62 percent asymptomatic carriers and 38 percent with manifest signs and symptoms of schistosomiasis. Of those with manifest signs and symptoms, 57 percent, according to Pesigan et al. ["Studies on Schistosoma japonicum ingestion in the Philippines: General considerations and epidemology," Bulletin World Health Organization vol. 18 (1958) pp. 345-355.] (1958), were mild cases, 39 percent were moderate and 4 percent were severe or very severe.7

More detailed longitudinal and cross-sectional surveys are needed to assess the proportion of infected persons who develop severe disease and the behavioral differences between those who are lightly and heavily infected with schistosomiasis.

In order to measure the public health importance of the disease, one must consider schistosomiasis as part of the spectrum of low-grade infections that, in combination with malnutrition, spend the human energy of the poor in the developing world. By itself, schistosomiasis, although serious, is infrequently directly fatal, but when considered in combination with malaria, hookworm, roundworm, river blindness, sleeping sickness, and other parasitic diseases, synergistic effects are known to occur. It is hard to separate the effects of the different diseases (except for the obvious effects like blindness or bloody urine); nonetheless, the combined impacts of the diseases contribute to shortened life spans and, possibly, to decreased economic productivity.

Because economic analyses of the public health effects of schistosomiasis have been unable to estimate the separate effects of the disease, they have frequently been inconclusive regarding the extent of the economic consequences of the disease.8 Despite this, investments in schistosomiasis control are still being made by governments and such donor agencies as the World Bank.9 The concern for schistosomiasis control will be discussed briefly later in this chapter. In chapter 3, economic studies will be described in more detail as a background for the cost-effectiveness analyses.

Schistosomiasis Control Measures

In this section, control measures and their costs will be briefly reviewed. It is hoped the review will indicate the possibilities for controlling schistosomiasis as well as the resource demands involved in such efforts.

Control measures are aimed at interrupting the schistosome's life cycle (see table 1-1). The ultimate effects of such measures are to reduce prevalence levels and incidence rates in the human population, the latter indicating if transmission has been halted.10 Initially, emphasis was placed on reducing snail populations by the use of molluscicides, since no effective drugs existed for community treatment until the 1960s. In addition, limiting human contact with snail-infested waters by the provision of protected water supplies or latrines was thought, at least until recently, to be difficult--if not impossible--to achieve. At present no immunization vaccine exists, which means that no permanent prophylactic control method is available.

Moreover, schistosomiasis is transmitted under diverse ecological conditions. Ranging from the temperate to tropical zones, the infection persists in areas of low or high rainfall and during hot or cold seasons. But Farooq reports, "Seasonal, climatic and hydrological changes have marked effects on the life cycle of the intermediate hosts, on the production of cercariae and on the transmission of infection."11 With such variety, the choice of control measures is necessarily a site-specific decision. It would be misleading to prescribe standardized regulations for control measures.

Closely related to the ecological diversity of transmission is the variety of economic conditions under which schistosomiasis exists. The differing economic conditions influence the range of resources available for schistosomiasis management and the willingness to pay for such efforts. Moreover, supplies, salaries, transportation, and other expenditures depend upon market prices of imports, wage rates, and the existing health delivery infrastructure. Prices vary from region to region as d...