- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies (Volume 2 Issue 3)

About this book

First Published in 1988. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cultural Studies (Volume 2 Issue 3) by JOHN FISKE in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ARTICLES

THE CHIPPEWA AND THE OTHER: LIVING THE HERITAGE OF LAC DU FLAMBEAU

GAIL GUTHRIE VALASKAKIS

Englishman! you ask me who I am. If you wish to know, you must seek me in the clouds. I am a bird who rises from the earth, and flies far up into the skies, out of human sight; but though not visible to the eye, my voice is heard from afar, and resounds over the earth!

Englishman! you wish to know who I am. You have never sought me or you should have found and known me.

(Keesh-ke-mun, Crane Clan, hereditary chief of the Lac du Flambeau Chippewa, quoted in Warren, 1885:373)

Since the earliest days of anthropology, ethnographers have tried to incorporate the experience of the researched through biography. This is reflected in the range of writings about individual Indians, the study of whose cultures has long been at the heart of ethnography. But biographies have always been marginal to cultural analysis, persisting as interesting documentation of individual memories, feelings, and beliefs. Unlike language, kinship systems, or social structure, narrative has not been valued as a source of scholarly analysis or as the lived experience of collectively constructed cultures.

Recent discussions about the practice of culture in everyday life have restored the value of narrative. Writing in cultural studies has reconceptualized culture itself as everyday action, discourse, and events: lived experience and public text. And ethnographers have considered anew the significance of the relationship between personal experience and authority, accuracy and objectivity, narrative and understanding (Pratt, 1986). This represents a tentative move away from the notion of the narrative Other as an object, reified through time-distancing in writing which reflects an ‘ethnographic present’ (Fabian, 1983:80), or research which is embedded in structures abstracted from action through anthropological analysis. This search moves toward what native people have long incorporated as lived experience: culture in the present woven with a kaleidoscopic past of intertwined experiences, representations, signifiers, and boundaries; history as heritage, living traditionalism.

In the writing of outsiders, native American traditional practice is often misunderstood as feathers and fantasy or, worse, as oppressive reification of the distant past. But Indian traditionalism is not these; nor is it lost in transformation or revived as a privileged expression of resistance. It is an instrumental code to action knitted into the fabric of everyday life, the ‘lived historicity of current struggles and the interminable intertwining of past and present’ (Walkerdine, 1986:182). It is cultural experience, ‘contested, temporal and emergent…. Representation and explanation—both by insiders and outsiders’ (Clifford, 1986:19), which situates the social field of current practice. Traditionalism is experienced collectively and individually as heritage, a multivocal past, re-enacted daily in the ambiguous play of identity and power.

Today, as in the past, Indian heritage is linked to Others in cultural struggle. Today, the arena is treaty rights, traditionalism contested, transformed, and enacted in the enveloping cultural distance between the Indian and the Other. In the always incomplete process of reconstructing the ‘collective reflexivity’ (Fabian, 1983:92) of lived cultural experience, biography is central to an ethnography which recognizes that ‘notions of the past and future are essentially notions of the present…an idea of one’s ancestry and posterity is really an idea of the self’ (Momaday, 1976:97).

I

We were very young when we began to live the ambivalence of our reality. My marble-playing, bicycle-riding, king-of-the-royal-mountain days were etched with the presence of unexplained identity and power. I knew as I sat in the cramped desks of the Indian school that wigwams could shake with the rhythm of a Midéwiwin ceremonial drum, fireballs could spring from the whispers of a windless night, and Bert Skye could (without warning) transform himself into a dog. I knew that my great-grandmother moved past the Catholic altar in her house with her hair dish in her hand to place greying combings of her hair in the first fire of the day, securing them from evil spirits. And I knew that I was yoked to these people through the silence of ancient actions and the kinship of the secret. Later I realized that we were equally and irrevocably harnessed to each other and this Wisconsin reservation land through indigence, violence, and ulcerated exclusion, recoiling among outsiders and ourselves; and that I was both an Indian and an outsider.

This land was reserved to the Lac du Flambeau band of Lake Superior Chippewa in the Treaty of 1854. The treaty didn’t become a contested charter in our daily lives until a century after its signing; but we have always known that this is Chippewa land.

The Chippewa are one of the Three Fires. We, with the nations of the Pottawatomi and the Ottawa, are shot with the Mégis shell in the secret ceremonies of rebirth that signify the Midéwiwin, a way of life ‘more powerful and impressive than the Christian religion is to the average civilized man’ (Hoffman, 1886:356). Together we followed the Mégis shell as it appeared above the water to direct our slow migration from the east. About 1300 we separated at the interface of Lake Superior and Lake Michigan, each moving inland to forests and lakes, which we held in trust through our respect for the grace in sighting an eagle and the fearful anxiety of the bear’s appearance. We who followed Keesh-ke-mun, chief of the interior Chippewa, were here at the heart of the Flambeau Trail, the trade route south from Lake Superior, when the black-robed Jesuits came in the early 1600s (Warren, 1885:114, 192). They came in consort with French furtraders, who became partners in our heritage through their practices of naming, commodifying, drinking, and taking country wives. Our daily lives became entangled in the interchange of furs and souls, of consumption and resistance; but our realities remained separate, bounded. François Malhiot, Northwest Company post manager at Flambeau in 1804 and 1805, wrote in his journal: ‘As a rule they [the Savages] possess all the vices of mankind and only think they are living well, when they live evil lives’ (Malhiot, 1910:204). Our understanding is stated in the words of a Métis historian: ‘It was prophesied that the consequence of the white man’s appearance would be, to the An-ish-in-aub-ag, an “ending of the world’” (Warren, 1885:117). And these attributes of the foreign intruder and the unknown savage, encased deep within the prism of Chippewa experience, are reflected in the representations of who we are and the nature of Others.

(The Milwaukee Journal, Oct. 14–17, 1984:2)

We are ‘Lac du Flambeau’ because furtraders, arriving at night during the spring spearing season, isolated this ageless custom and attached it to us for ever. They were awed by the sight of torch-lit canoes moving silently along the shallows of the lakes, silhouetting Indians poised to spear fish. We have identified with their romanticized image of a ‘Lake of Flames’ from that day to this. We were always Waus-wa-im-ing, ‘People of the Torch’. But between 1640 and 1835 one and sometimes two and three trading posts at Flambeau were sites of exchange, defining us as traditional trappers endlessly attracted to the sociability of rum: the humor, the quarrels, the deadening silence (Bokern, 1987). Now we are Lac du Flambeau, known to each other through reconstructions of the past and Christian names, many French, transformed from our Ojibway language, today pronounced as English. Our names, like this land, were claimed in Chippewa blood when the trading period forced alliances through intertribal warfare. We fought for ourselves, for the French, and, refusing the demands of the British, we fought for the Americans.

In 1737 the Chippewa, the Fox, and the Dakota Sioux began 150 years of dispersed, desperate battle to hold this land with its intrinsic resources and its trading empires. When the Fox were driven south in the mid-1700s, we fought the Dakota (Bokern, 1987:11, 14). The last memorable battle between the two tribes took place in Flambeau in 1745, and we are forever pierced by what we experienced. After days of scattered fighting, the Dakota were driven to Strawberry Island in Flambeau Lake just as evening fell. The Chippewa regrouped, waiting for the dawn’s final attack. Surrounding the island at the first light of day, we found the enemy had vanished, leaving a presence more powerful than bodies, scars on the land, or worldly artifacts. Near the Dakota campsite stood an enormous rock, a panoptic gargoyle, white in its newness, confronting the Old Village across the water with the ambiguity of our spiritual heritage.

Like the violence which spawned it, Medicine Rock became involved in the migrations of newcomers, Indians and Others, who found their way to Flambeau. My great-grandparents were among the first to stay, thirty years after the reservation was established in 1854. They were Christian half-breeds living near Chippewa Falls, where my great-grandfather was an interpreter for a French furtrader. They married in 1883, and came up-river at the urging of Ke-nis-te-no, my great-grandmother’s grandfather, who was a signatory of the treaty which, in 1887, enrolled the Lac du Flambeau band and granted land to tribal members. The practices signified by my great-grandparents’ religion and bloodlines set them apart as the Indians’ struggle to defend their presence shifted to the inner arena of community. It was two years before my great-grandparents were allowed to approach Medicine Rock, and they never left the customary tobacco there. And this difference conceived in experience was fixed by a policy of appeasement. When individual Chippewa were granted land through the Allotment Act, full-bloods were given 160 acres, disclaimed half-breeds 80 acres. Our family’s posterity was preserved when my great-grandmother’s name, written on the tribal roll of 1895, was omitted as the membership was read aloud to the old full-blood chiefs.

My great-grandfather’s land was allotted at Lac Courte Oreilles reservation; my great-grandmother’s sister was enrolled in the Bad River band. We were a region of Chippewa even then, clans and cousins of the An-ish-in-a-beg nation, gathered and restricted from a migratory cycle of hunting to the south in winter, moving north in summer to gather maple sap and wild rice and to fish. We were called a ‘timber people’ (Hoffman, 1886:149); but this land, so attractive to outsiders for its cover of white pine, lacked underbrush to support large game. Especially here, where ‘the Pokegama arm of the Lac du Flambeau…abounds with fine fish, which the Indians take in great numbers in gillnets and with the spear’ (Owen, 1852:280), our lifeblood was sustained in the nurture of spring harvesting and the presence of Gitche Manitou, the Great Spirit.

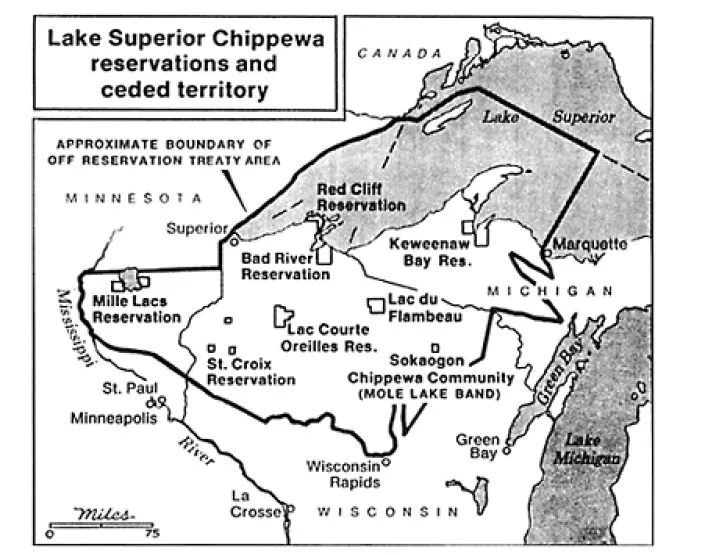

The Treaty of 1854 created six Chippewa reservations, small, irregular configurations of land reserved from territory ceded or sold to the United States in 1837 and 1842, when treaties became ritualized means for the extraction of copper, iron, and timber. A furtrader wrote: ‘To my certain knowledge the Indians never knew that they had ceded their lands until 1849, when they were asked to remove therefrom’ (Armstrong, in Bartlett, 1929:68). We remained sutured to this land through the starved silence of the abandoned fur trade and two government removal orders before the reservation was conceded. Little Bee, the Flambeau chief, walked with Chief Great Buffalo on the footpath of resistance worn by the patience of delegations to Washington in 1852 to protest the order to leave Wisconsin; and in 1862 to petition for a larger land base on the new reservation, and the promised annuity payments (Bartlett, 1929:74, 82). Our elders witnessed the starvation of the Chippewa who marched west to Minnesota. We from Flambeau did not move, and, finally, letters to the President broke the stubborn stillness. One was from the Wisconsin Legislature requesting reservations, for ‘Chippewa Indians are peaceable, quiet and inoffensive people’ (Rutlin, 1984:16). In 1854 our elders signed in relief, framing the heritage of our traditional practices: ‘the privilege of hunting, fishing and gathering wild rice upon the lands, the rivers and the lakes included in the territory ceded is guaranteed to the Indians, during the pleasure of the President of the United States’ (Klapper, 1904:492).

When the Chippewa were enrolled as tribal members, the quiet indifference was shattered by the boom and bust of sawmills. Loggers began to cut timber from land allotted to individual Indians in 1887, and, when we were decreed competent to sell our allotments in 1910, Flambeau stood at the epicenter of the logging era. We who had always dreaded the anxiety of confronting a mythical, man-eating Windigo, a bear or a stranger, now encountered a town, magnetic in the bustle and brawl of work and whiskey; repulsive in the corruption and control of agency and enterprise. In 1909, when the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs came to Flambeau, one after another, Headflyer, John Martin, Louise Chapman, Ma-kwe-gon, John Wildcat, my great-grandmother, and many others told Senator Robert la Follette of their problems with land allotments, payment of timber annuities and credit at the company store. My great-grandmother testified that she (like Headflyer) had a license to start a store, but

Mr Herrick [the mill owner] said that anybody that went into business like that, that he would starve them out…. He also said that no one could start a store here, that he was the ‘Rock of Ages’ in this place, and that frightened me, and I thought that it would not be very well to go against him. (Conditions of Indian Affairs in Wisconsin, 1910:775)

Loggers brought settlers, outsiders from a distance who came to stay. In the acrimony of this intrusion, we drove the first Protestant missionary off the reservation in 1886. But the Catholic and Protestant churches, which now stand staring at each other on opposite sides of the road between the Old Village and the new town, emerged in the ambivalence of the last decade of the century. We from the clans of the Crane, the Snipe, and the Marten wrapped the Midéwiwin drum in white cloth and secured it in Jim Bell’s house-of-thekeeper, in the shadow of Medicine Rock. We incanted the hymns and prayers of Christian rebirth through the typhoid epidemic of 1887 and the smallpox epidemic of 1902. My great-grandmother witnessed 500 baptisms, names ornately framed on the walls surrounding the Catholic altar in her house. Like the names, we were suspended between Christian ritual and Chippewa custom, including the newly incorporated practice of drinking. But we never surrendered the secrets of the Mégis shell, with its dreams and fasting and sweats for ‘pimadiziwin, life in the fullest sense; life in the sense of health, longevity and well-being’ (Hallowell, 1967:294).

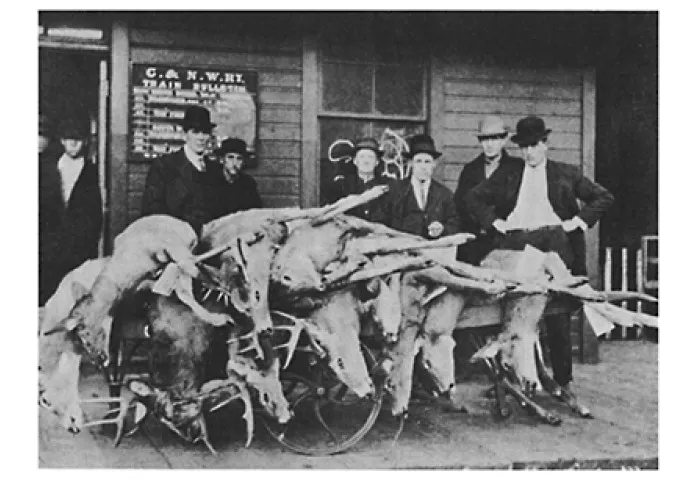

Settlers and tourists in northern Wisconsin in the first decade of this century

In 1895 a government residential school in Flambeau folded new generations of Chippewa into the discipline and distance of acculturation enforced through English, farming, and contact with children of foreign tribes. And Flambeau grew as a construction of Others between 1908 and 1934, when the Indian Agency centralized the bureaucratic power of writing and wardship in a compound of white-frame buildings. But, long after, my great-grandfather told of Old Man Sky at Odanah who could shake three wigwams at once; my great-grandmother took my father to the drumming of the Midéwiwin, wearing her cross; and, when the medicine man An-a-wa-be died, the fear of his power was immobilizing. Four days passed before his women dressed him and buried him in the intercession of night.

My great-grandparents moved closer to the new town, consigned to loggers in sawdust and sweat for the invited and the non-Indian. There they learned English, witnessed the disruption of development, and eventually built a rambling structure of yearly additions for the millowners. They sent their only child to a Catholic school in St Paul, Minnesota, when she was 7. She never came back to the reservation except in summer and, like her children and their children, she married a non-Indian. My father was a Flambeau Chippewa during the summer, a student in Minneapolis during the winter. He chose the ancestry of his Indian name, Ke-nis-te-no, when he came to Flambeau during the Depression of the 1930s; and he stayed, first for his grandparents, then for himself. He is here still with my mother, who came to Flambeau as a tourist from Chicago at 14 and has lived here for fifty years. Like many others since, my brother and I are living boundaries between the city and the reserve, the Chippewa and the outsider.

In 1912 the judgment of Gitche Manitou settled upon the deteriorating reservation. The sawmills closed, the owners left, and a giant, man-eating Windigo bellowed a cyclone which destroyed the Old Village. In the silence that followed, the young and the mixed-blood were the first to move into the deserted mill houses of the new town. The Old Village and the families of the full-bloods remaining there were constituted for ever traditional.

Our land was largely stumps and cutover brush meandering among 126 lakes within the township of Lac du Flambeau decreed by the state in 1900. The new underbrush now supported deer; but it was the lakes and the fish of our spring spearing grounds which, through the logger’s legacy of alienated land, now attracted outsiders. In 1897, the same year that liquor was forbidden on the reservation, the Chicago and Northwestern railroad snaked through Flambeau, at first to carry logs out, then to carry tourists in. Chippewa land within our borders became the currency of contact until land allotments and sales were stopped for the last time in 1933 (McKinsey, 1937:2). By then, almost half of our reserved lands were privately owned, mostly by non-Indians:

Big George Skye and my father, Ben Guthrie, at my great-grandparents boarding house, 1913

The most desirable and valuable portions of lands along the lake shores have practically all been alienated [from Indians] by white owners and much of the remaining land, owned by Indians, is swamp lands, cut over or burned over timberlands and for the most part is of little value.

(McKinsey, 1937:1)

We still brood with the burial mounds on Strawberry Island, now owned by a businessman from Chicago who has never dared to disturb the spirits there.

In 1913 my great-grandparents began building a new hotel, a beacon for city fishermen and city families which spawned into cottages, boats, and a bar. During the nex...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Articles

- Kite

- Reviews