![]()

Part I

Studies of climatic history and its effects on human affairs and the environment

![]()

This wide-ranging essay is the substance of an article in the Encyclopaedia Britannica Book of the Year 1975. Portions have been omitted which would be duplicated in other chapters. It gives an introductory survey of the development of climate over the Earth from the last ice age to today.

Climate is always changing. The fluctuations of weather and climate take place on all time-scales, from the gusts and lulls of the wind, which occur within a fraction of a minute, to the shifts of regime over hundreds of millions of years associated with continental drift and wandering of the poles. Fortunately, however, for the development of life on the Earth and in particular for the evolution of contemporary life forms, the range of the temperature changes has been limited. Since the first appearance of life, there have presumably always been regions of the Earth where the air and water temperature remained generally between 20 deg and 30 degC (70 deg and 86 degF) and extensive regions where the limits of 0 deg and about 35 degC (32 deg and about 95 degF) were never far exceeded nor for more than a few hours at a time. This limited range bears witness that the sun must have been a reasonably constant star and the Earth a planet hospitable to the survival and spread of life. Nevertheless, the changes in the Earth's climate that have occurred have brought innumerable local and regional disasters and have repeatedly challenged the tolerance and adaptability of human and all other living entities.

The greatest and quickest changes of climate, and of the environment dependent on climate, have been connected with the onset and ending of ice ages and with fluctuations near the ice margin at times when the Earth is partly glaciated, as it is at present. The mean temperature in Iceland, for example, rose by about 2 degC during the global warming between AD 1850 and 1950, and the corresponding change averaged over the whole Earth was a rise of around 0.5 degC. These shifts not only moved the limits of the vegetation belts equatorward or poleward, and up and down the mountains, but also affected the rainfall in continental interiors and the position and development of the desert belts. As the ice masses built up on land or melted away, sea-level changed by as much as 100 m between the extremes of ice-age and interglacial climates.

The greatest losses of life directly attributable to weather and climate have resulted from coastal floods, specifically those produced by storm winds and tidal surges at times when the world sea-level had been rising during preceding decades or centuries of warm climate. The histories of China, the Bay of Bengal, and the North Sea coasts of Europe provide many instances in which hundreds of thousands of people have died in such sea floods.

Whether the climatic stress for humanity, animals and plants presented itself in the form of a change in the prevailing temperatures, in aridity, or in a greater incidence of floods and storms, survival often depended on migration. In our more recent history, we have enabled ourselves and our crops and animals to survive and flourish beyond the limits previously imposed by nature, using artificial indoor climates and irrigation; this ability to transcend nature's limitations now depends, however, on the use of a great deal of energy (especially oil) and often on the use of 'fossil' water in underground strata, which may also be limited.

Causes of climatic variation

The causes of climatic change can be classified in four general categories. The first chiefly concerns changes in the Earth's geography. It includes drift of the continents, which change their positions relative to each other and to the poles; uplift and erosion, which change the magnitude and disposition of mountain barriers and thereby affect the flow of the winds; and changes during the Earth's history in the total mass and chemical composition of the atmosphere and oceans. This category also includes variations in the energy output of the sun and changes in the heat flow from the Earth's interior (probably almost always of minor importance). The first three items in this group deal with changes that generally become significant only over tens or hundreds of millions of years.

The second category of causes of climatic change comprises cyclical variations in the Earth's orbital arrangements. These include the angle of tilt of the Earth's rotation axis to the plane of the orbit, which varies by a few degrees over a cycle of 40,000 years and changes the latitudes of the tropics and polar circles and the angle of elevation of the sun. Also in this category is the precession of the equinoxes – the progressive change in the position of the Earth in its elliptical orbit for any given time of the year. This 21,000-year cycle alters the distance of the Earth from the sun at any given season. There is also a 100,000-year cycle in which changes in the ellipticity of the Earth's orbit affect the yearly variance of the Earth's distance from the sun.

The third category consists of changes in the transparency of the Earth's atmosphere to incoming (mostly short-wave) and to outgoing (mostly long-wave) radiation. The best-demonstrated effects under this heading are those that have followed volcanic explosions which throw great quantities of fine dust into the stratosphere, creating a veil there which characteristically spreads over the Earth and lasts for two to three (occasionally as long as seven) years. While the veil lasts, temperatures rise in the stratosphere, due to direct absorption of solar radiation there, and are lowered at the surface of the Earth, due to loss of incoming short-wave radiation. Changes of cloudiness and in the atmosphere's content of water vapour, carbon dioxide, and other substances that are not transparent to radiation on some wavelengths also affect the radiation balance. Some of these vary as a result of the weather itself. Others are increasingly contributed by human activities (though perhaps not yet in sufficient quantities to affect climate).

The fourth category comprises the changes in the amounts of heat absorbed and given off at the surface of the Earth. These are due to variations in the extent of ice and snow, in the distribution of vegetation and of waterlogged or parched ground, and in the amount of anomalously warm or cold water on the ocean surface as a result of variations in the amount of sunshine or up-welling, respectively. These changes, like some mentioned in the third category, are produced by the weather itself and may in some cases increase the likelihood of persistence of the weather pattern that produced them.

Climate during the last billion years

Through the longest stretches of geological time the Earth had only warm climates, with no great polar ice sheets, though it is now thought that there may have been many periods during which any landmasses that were near the poles bore 'permanent' ice. If one accepts this view, the development of the greater ice ages chiefly depended on continental drift to place a continent at one or the other of the Earth's poles or, at least, to put landmasses of continental extent in high latitudes. However, the matter seems to be also affected by astronomical and solar variations. Evidence of the occurrences of greatest extent of ice in the past points to a fairly regular interval of nearly 300 million years, which may be explainable by gravitational effects of the rotating galaxy upon the sun's activity and output. And in each of the times when extensive ice occurred there seem to have been alternations between ice-age conditions and interglacial periods, which, as in the Quaternary (the last one million years approximately), may be attributed to the effects of the Earth's varying orbital arrangements (and tilt of the polar axis) upon the gain and loss of radiation from the sun in summer and winter.

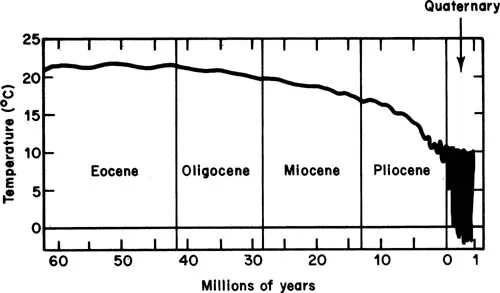

Figure 2.1 Average temperature in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere over the last 60 million years declined gradually until the Pliocene when it began to drop more sharply. Climate historians have increased the estimated number of ice-age/interglacial fluctuations in the Quaternary to about ten since this diagram was drawn. The time-scale is enlarged for the last one million years.

For reasons probably among those listed but which cannot yet be determined, there were important fluctuations that brought cooler climates at times during the Mesozoic era (between 225 million and 65 million years ago). One of these, about the end of the Cretaceous period and beginning of the Cenozoic era (about 65 million years ago), may have been associated with the extinction of the dinosaurs, which were presumably not adapted to withstand the cold as well as their warm-blooded contemporaries.

During the Tertiary period of the Cenozoic (65 million to 2.5 million years ago) a greater and more persistent cooling set in. In the late Tertiary (Pliocene epoch), superposed fluctuations on a time-scale of about 40,000 years can be traced. These fluctuations were presumably associated with the cyclical variation of the Earth's axial tilt (obliquity), and some of them are now thought to have produced conditions that began to approach the severity of the Quaternary (or Pleistocene) ice ages. The latest evidence suggests that it was during the Pliocene that the first races of humanity emerged as a distinct species from the apes. Perhaps it was a superior ability to adapt to the changes of climate and of the terrestrial environment, even in the warmer regions of the Earth, that enabled the new species to thrive. There is little doubt that it was the emergence during the Tertiary of a geography similar to that of the present, with a south polar continent and an almost complete land ring about the North Pole, that made possible the development of increasingly extensive ice sheets, thus cooling the oceans and therewith the whole Earth (see figure 2.1).

Recent evidence from oxygen-isotope measurements on carbonatebearing sediments of the Pacific Ocean near the Equator suggests that the end of the Pliocene and beginning of Pleistocene is marked by a sudden change in the pattern of oscillations: from that time onward the temperature history is dominated by oscillations of close to 100,000 years in extent. Whether this means that some astronomical event occurred that made the variations in the ellipticity of the Earth's orbit more important than before is not yet clear, but the periodicity seems to coincide with those variations. The 40,000-year periodicity is still present but seems to play a somewhat subsidiary role. This latest evidence suggests that there have been about ten major developments of glaciation during the last one million years of the Quaternary period, though of varying severity and, as always, with every kind of shorter-term fluctuation superposed.

The last ice age and early human beings

During the last glaciation primitive people made what was probably an easy living by hunting the large grazing animals – reindeer, bison, mammoth – on the open steppe-tundra lands in what is now France and elsewhere on the European plains. They have left a record of their life and of this fauna in cave-wall paintings at Lascaux, France, and Altamira, Spain. During the last glaciation the first people probably entered the Americas, travelling from Asia about 35,000–15,000 years ago over the broad grassy lowland which is now the Bering Strait and Bering Sea, thanks to the drop of world sea-level. The same circumstance probably allowed the first aboriginal people to pass from Asia to Australia approximately 25,000 years ago.

After the ice age

The postglacial climatic regime developed rapidly, particularly in Europe, though there was at least one drastic setback when, for a period of 500 or 600 years, in the ninth millennium BC, glacial conditions returned or readvanced. With the postglacial warming, there came a time when the rivers were swollen enormously, particularly in summer, by the melting ice. Gravels and sand were rapidly deposited and quickly produced thick deposits in some places; lakes formed and sometimes quickly silted up and completely disappeared. The landscape was changing rapidly, but the...