eBook - ePub

Electrochemical Techniques in Corrosion Science and Engineering

- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Electrochemical Techniques in Corrosion Science and Engineering

About this book

This book describes the origin, use, and limitations of electrochemical phase diagrams, testing schemes for active, passive, and localized corrosion, the development and electrochemical characterization of passivity, and methods in process alteration, failure prediction, and materials selection. It offers useful guidelines for assessing the efficac

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Electrochemical Techniques in Corrosion Science and Engineering by Robert G. Kelly,John R. Scully,David Shoesmith,Rudolph G. Buchheit in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias físicas & Ciencias de los materiales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias físicasSubtopic

Ciencias de los materiales1

Introduction

Corrosion can be defined as the deterioration of a material’s properties due to its interaction with its environmnet. The demands for long-term performance of engineering structures over a wide size scale continue to increase. As microelectronic structures decrease in size, smaller amounts of dissolution on interconnects in integrated circuits can lead to the failure of large computer systems. The long-term storage of nuclear waste may represent man’s most compelling engineering challenge: containment of high-level radioactive material for thousands of years. In both cases, as well as in many in between, the corrosion engineer has a primary responsibility to provide guidance throughout the design, construction, and life process in terms of material selection, environment alteration, and life prediction. Over the past thirty years, the use of electrochemical methods for probing corrosion processes has increased to the point where they represent an indispensable set of tools. The overarching goal of this book is to provide the foundation for corrosion engineers to use electrochemical techniques as part of the tool kit they apply to corrosion concerns.

This introduction briefly reviews topics that underlie the remainder of the book. Most of these topics will be familiar from high school or college chemistry. Nonetheless, the topics are generally given short shrift in standard chemistry syllabi, so their importance with respect to corrosion is emphasized here.

I.CHEMICAL VS.ELECTROCHEMICAL REACTIONS

Chemical reactions are those in which elements are added or removed from a chemical species. Purely chemical reactions are those in which none of the species undergoes a change in its valence, i.e., no species is either oxidized or reduced. Electrochemical rections are chemical reactions in which not only may elements be added or removed from a chemical species but also at least one species undergoes a change in the number of valence electrons. For example, the precipitation of iron hydroxide, Fe(OH)2, is a pure chemical reaction:

Fe2++2OH-→Fe(OH)2

(1)

None of the atoms involved have changed its valence; the iron and oxygen are still in the divalent state, and the hydrogen is still univalent. One way to produce the ferrous ion needed in the above reaction is via the oxidation of metallic (zero valent) iron:

Fe→Fe2++2e-

(2)

In order for this reaction to occur, the two electrons produced must be consumed in a reduction reaction such as the reduction of dissolved oxygen:

O2+2H2O+4e-→4OH-

(3)

If the two reactions are not widely physically separated on a metal surface, the chemical reaction between the hydroxide and ferrous ions can produce a solid on the surface. Thus chemical and electrochemical reactions can be (and often are) coupled.1 The electrochemical methods described in this book can be used to study directly the wide range of reactions in which electrons are transferred. In addition, some chemical reactions can also be studied indirectly using electrochemical methods.

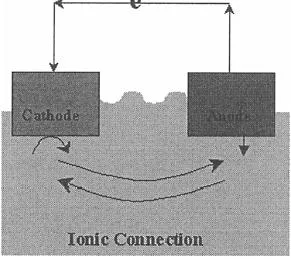

The vast majority of engineering materials dissolve via electrochemical reactions. Chemical processes are often important, but the dissolution of metallic materials requires an oxidation of the metallic element in order to render it soluble in a liquid phase. In fact, there are four requirements for corrosion: an anode (where oxidation of the metal occurs), a cathode (where reduction of a different species occurs), an electrolytic path for ionic conduction between the two reaction sites, and an electrical path for electron conduction between the reaction sites. These requirements are illustrated schematically in Fig. 1.

All successful corrosion control processes affect one or more of these requirements. For example, the use of oxygen scavengers affects the cathodic reaction rate possible. Isolating dissimilar metals with insulating materials attempts to remove the electrical path. Most organic coatings serve to inhibit the formation of an electrolytic path. Thus, when evaluating a corrosion process or proposed mitigation method, a first-pass analysis of the effects of it on the four requirements can serve to structure one’s thinking.

A simple calculation demonstrates the tremendous power of electrochemical reaction rate measurements due to their sensitivity and dynamic range. Dissolution current densities of 10 na/cm2 are not tremendously difficult to measure.

1Bard and Faulkner (1) is an excellent source of information on the intricacies of such coupling.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of four requirements for corrosion. Note that the anode and cathode can be on the same piece of material.

A metal corroding at this rate would lose 100 nm of thickness per year.2 On the other end of the spectrum, measurements of reaction rates of several to hundreds of A/cm2 are needed in some transient studies of localized corrosion. A dissolution rate of 100 A/cm2 corresponds to a penetration rate of 1 km/s. Fortunately for modern society, such penetration rates last in practice for far less than one second! Thus modern instrumentation allows the measurement of dissolution rates over more than 10 orders of magnitude with accuracy on the order of a few percent.

The issues of accuracy and precision are often controversial in discussions of corrosion electrochemistry. Analytical electrochemists can achieve high accuracy and precision through the strict control of variables such as temperature, solution composition, surface condition, and mass transport. Throughout this book, the effects of these and other variables on corrosion processes are highlighted. Unfortunately, in practice, close control of such important parameters is often impossible. In addition, corrosion systems are generally time-varying in practice, further complicating reproducibility. This situation can be disturbing for physical scientists new to electrochemical corrosion measurements who are used to more control and thus more reproducibility in instrumental measurements.

Nonetheless, they become more comfortable with experience, as they realize that in most cases, getting the first digit in the corrosion rate right is both a necessary and a sufficient condition for job security.

2In most applications, this would be considered outstanding corrosion resistance, but for a nuclear waste storage vessel needing 100,000 years of service, the corrosion allowance would need to be at least 10 cm.

II. FARADAY'S LAWS OF ELECTROLYSIS

In the early 1800s, Michael Faraday performed superb quantitative experimental studies of electrochemical reactions. He was able to demonstrate that electrochemical reactions follow all normal chemical stoichiometric relations and in addition follow certain stoichiometric rules related to charge. These additional rules are now known as Faraday’s laws. They can be written as follows:

Faraday’s First Law: The mass, m, of an element discharged at an electrode is directly proportional to the amount of electrical charge, Q, passed through the electrode.

Faraday’s Second Law: If the same amount of electrical charge, Q, is passed through several electrodes, the mass, m, of an element discharged at each will be directly proportional to both the atomic mass of the element and the number of moles of electrons, z, required to discharge one mole of the element from whatever material is being discharged at the electrode. Another way of stating this law is that the masses of the substances reacting at the electrodes are in direct ratio to their equivalent masses.

The charge carried by one mole of electrons is known as 1 faraday (symbol F). The faraday is related to other electrical units because the charge on a single electron is 1.6×10-19 C/electron. Multiplying the electronic charge by the Avogadro number 6.02×1023 electrons/mole electrons tells us that 1 F equals 96,485 C.

These empirical laws of electrolysis are critical to corrosion as they allow electrical quantities (charge and current, its time derivative) to be related to mass changes and material loss rates. These laws form the basis for the calculations referenced above concerning the power of electrochemical corrosion measurements to predict corrosion rates. The original experiments of Faraday used only elements, but his ideas have been extended to electrochemical reactions involving compounds and ions.

By combining the principles of Faraday with an electrochemical reaction of known stoichiometry permits us to write Faraday’s laws of electrolysis as a single equation that relates the charge density (charge/area), q, to the mass loss (per unit area), Δm:

(14)

Taking the time derivative of the equation allows the mass loss rate to be related to the dissolution current density:

(5)

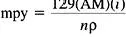

In many cases, a penetration rate, in units of length/time, is more useful in design. The inclusion of corrosion allowances in a structure requires an assumption of uniform penetration rate. The most common engineering unit of penetration rate is the mil per year (mpy). One mil of penetration equates to a loss in thickness of 0.0001. Corrosion rates of less than 1 mpy are generally considered to be excellent to outstanding, although such adjectives are highly dependent on the details of the engineering scenario. A rule of thumb is that 1μA/cm2 is approximately equivalent to 0.5 mpy for a wide range of structural materials, including ferrous, nickel-, aluminum-, and copper-based alloys. For more extract calculations, the following formula can be used:

(6)

where

mpy=penetration rate (mils per year)

AM=atomic mass (g)

i=corrosion current density (mA/cm2)

ρ=density (g/cm3)

n=number of electrons lost per atom oxidized

mpy=penetration rate (mils per year)

AM=atomic mass (g)

i=corrosion current density (mA/cm2)

ρ=density (g/cm3)

n=number of electrons lost per atom oxidized

Throughout the text, distinctions are made between current, i.e., the rate of a reaction, and current density, i.e., the area-specific reaction rate. The combination of Faraday’s laws described above involves current density rather than current. The current, usually symbolized with a capital I, has units of amperes and represents an electrical flux. The current density, usually symbolized with a lower case i, has units of amperes per unit area, e.g., A/cm2. Under a given set of conditions (i.e., potential, metal a...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE

- 1: INTRODUCTION

- 2: ELECTROCHEMICAL THERMODYNAMICS AND KINETICS OF RELEVANCE TO CORROSION

- 3: PASSIVITY AND LOCALIZED CORROSION

- 4: THE POLARIZATION RESISTANCE METHOD FOR DETERMINATION OF INSTANTANEOUS CORROSION RATES

- 5: THE INFLUENCE OF MASS TRANSPORT ON ELECTROCHEMICAL PROCESSES

- 6: CURRENT AND POTENTIAL DISTRIBUTIONS IN CORROSION

- 7: DEVELOPMENT OF CORROSION MODELS BASED ON ELECTROCHEMICAL MEASUREMENTS

- 8: THE USE OF ELECTROCHEMICAL TECHNIQUES IN THE STUDY OF SURFACE TREATMENTS FOR METALS AND ALLOYS

- 9: EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES