- 102 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Theory of Money

About this book

This title, first published in 1965, provides an analysis of the forces and mechanisms governing the formation of the overall level of money prices. Even though this problem has a long history, and in spite of its obvious practical importance, it remains one of the most poorly understood questions in economic theory. This title will be of interest to students of monetary economics and the history of economic thought.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theory of Money by Jacob T. Schwartz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

APPENDIX I

Remarks on Mathematical Economics and Economics Generally

It was the intent of von Neumann and Morgenstern that their general theory of games should provide the basis for an economic theory, and even a general theory of society. While this program has by no means been forgotten, hardly any progress has been made toward its accomplishment since the appearance of their Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. The reason lies in the very rapid growth in complexity of the analysis of solutions of n-person games as n increases beyond 2. The formidable character of the obstacles to be met is apparent, for instance, in the long delay in settling the question of existence or non-existence of solutions of games in general. Now, as von Neumann and Morgenstern point out, significant applications to economics depend on the treatment of n-person games for large n; then how to proceed? A difficulty of just this sort was met and overcome in the history of physics. Two hundred and fifty years after Newton, the ability of mechanics to solve the n-body problem still extends no farther than n = 2. The application of mechanics to thermodynamics depends on the analysis of the motion of n particles, where n ~ 1023. This line of thought suggests that the application of game-theory to economics must be based on a new viewpoint in game theory itself; the analog in the present context of the Gibbsian statistical viewpoint in mechanics. I should like to suggest that the necessary principle is that contained in Nash’s notion of equilibrium point. (Cf. the first section of Lecture 5 for the formal definition of “game” and “equilibrium point.”) The general von Neumann-Morgenstern notion of solution of a game involves a consideration of all possible coalitions among the players, the strength of all coalitions, internal arrangements of reward and sanction within each coalition, and so forth. In the Nash concept, on the other hand, each player takes the context in which he finds himself, determined by the moves of the possibly very large number of other players, as given, and makes an individual, personally optimal adjustment. This latter notion corresponds to the workings of an established economy (or even society); the former always calls the social constitution into question, and asks: is any group within the economy strong enough to bring about its revision in toto? Thus, if one takes a view of economics rigorously consistent with the von Neumann-Morgenstern theory, economic analysis would necessarily include a theory of such things as congressional negotiations on fiscal, tax, and tariff policy. However interesting such questions may be, they do not belong to economic theory in the limited sense ordinarily understood. Thus the von Neumann-Morgenstern definition is too broad. But it is also too narrow. Indeed, the von Neumann-Morgenstern notion of a game solution excludes many of the phenomena which economics recognizes in the real world and is accustomed to describe. The notion of equilibrium point, narrower in the appropriate direction, broader in the appropriate direction, takes in these phenomena.

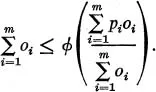

Let us consider, for example, a simple situation to which ordinary supply-demand theory can be applied, competition for sales in a given external market. We set up a model game as follows. Let there be N players, i.e., N “sellers,” the ith seller having a “stock” of si “units of goods” obtained by him at a “unit cost” ci. Each seller offers a part or all of his stock of goods for sale at a price pi. Certain of the offers made are accepted, in accordance with the following rule: a monotone decreasing function ϕ(p) (external market demand schedule) is given. If the offers made, arranged in order of increasing price, are offers of o1 units at price p1, o2 units at price p2, …, oN units at price pN, then the first m are accepted, m being the largest integer such that

i.e., offers begin to be declined at that point where the total of offers accepted first threatens to rise above the amount demanded in view of the average cost of accepted offers. The payoff to the ith player is (pi − ci)oi if his offer is accepted, zero if his offer is rejected.

What are the equilibria of this game?

It is not hard to answer the question. Suppose that a certain pattern of offers constitute an equilibrium. Plainly, no seller will at equilibrium make any offer lying below his own cost. At equilibrium, no seller can be able to raise the price of his offer without causing it to be declined; thus no offer accepted can lie at a lower price than any other offer accepted. Hence at equilibrium all the accepted offers must be made at the same price pe. A seller whose offer is rejected can always hope to increase his payoff from zero by lowering the price of his offer, provided that the revised price lies above his cost. Thus, the price pe must lie below the cost of each seller whose offer is rejected. At equilibrium, no seller can be able to increase the size of his offer at a price that will be accepted; thus, each seller whose cost is less than pe must sell the whole of his stock. It follows that pe is determined by the condition that the total stock of goods in the hands of sellers whose unit cost is less than pe shall equal the total demand ϕ(pe) for goods at price pe. This is, of course, merely the ordinary determination of perfect market price by the intersection of a supply and a demand schedule. Conversely, it is not hard to see that the pattern of offers described above does define a game-theoretical equilibrium in the sense of Nash.

All this merely recapitulates a standard elementary result on the equilibrium of a perfect market, and even the ordinary discussion of the mechanism underlying such an equilibrium, merely dressing a familiar heuristic argument in the uniform of mathematical formalism and rigor. Let us now note that the supply-demand equilibrium which we have described need not have anything to do with the solution of our model game in the sense of von Neumann and Morgenstern. To see this, let us first arrange the sellers in order of increasing cost. Let pe be the equilibrium price, which we have seen to be determined by the equation

(equilibrium price = unit cost of marginal seller). Let us now suppose that the demand schedule ϕ has the property that there exists an m′ > m such that the demand ϕ(p′) determined by

differs sufficiently little from ϕ(pe) that p′ϕ(p′) > peϕ(pe) (even though ϕ(p′) < ϕ(pe)). That is, we assume an external demand which is relatively inelastic over a certain price interval. Then, if the m lowest-cost sellers secure the cooperation of sellers m + 1 through m′ they can agree to offer goods for sale at a monopoly price p′, thereby obtaining a collective income p′ϕ(p′); since p′ϕ(p′) > peϕ(pe), it is then possible for each of the first m players to enjoy a higher payoff, even if a positive premium is payed to secure the cooperation of every seller from m + 1 through m′. It is obvious that every seller would regard the new arrangement as preferable to the old equilibrium. Thus, in the von Neumann-Morgenstern sense, the ordinary supply-demand equilibrium of economic theory need be no solution. To obtain the solution in von Neumann and Morgenstern’s sense, one must consider the detailed form of the demand schedule, the possible earnings of all oligopolistic “coalitions” which can be formed among the sellers, the schedule of premia which such oligopolies can and will be willing to offer to other sellers to secure cooperation with the aims of the oligopoly, etc.

From this we see that the von Neumann-Morgenstern solution of a game may involve a complex system of agreements, subsidiary payments, and sanctions, difficult to maintain among a large number of players, or even impossible to establish if administrative energy and time are limited. It is precisely this difficulty which provides the point d’entree for Nash’s notion of equilibrium point. Here each player, without consulting the others, does what is best for himself. That this latter concept is descriptive of many social situations which the von Neumann-Morgenstern concept fails to detect is easily recognized. A traffic jam is surely not the optimum collective solution to the problem of automobile flow on roads. Nonetheless, traffic jams are real phenomena. The Nash theory admits this; the von Neumann-Morgenstern theory insists that the drivers will make a collective agreement calculated to avoid traffic tie-ups. True! A traffic signal system and a traffic police will eventually be established. But in judging that such a “constitutional” change is extraordinary we also judge that the Nash viewpoint is to be preferred over the von Neumann-Morgenstern viewpoint for description of the ordinary workings of an economy or society. And, after all, the traffic control system, even when established, operates not so much through a social contract among drivers as through a mechanism which, by imposing suitably large fines, changes each individual driver’s system of payoffs and thereby shifts the equilibrium of a still decidedly non-cooperative game.

It may also be pointed out that the mathematical notion of equilibrium point corresponds almost exactly to Adam Smith’s notion of an overall “dead hand” operating through individual efforts at self-betterment. By analyzing individualistic equilibria under various sets of rules, economic theory hopes to uncover the advantages and disadvantages of various more or less far reaching socio-economic rearrangements. By adopting the equilibrium-point view, we confirm the ordinary division between economic analysis on the one hand and political-historical analysis on the other.

The von Neumann-Morgenstern concept of “solution” is thus seen to be too far-reaching to be entirely appropriate as a tool of economic analysis; the Nash notion of equilibrium point, however, is seen to be highly appropriate. To the extent that the latter part of this statement is reliable, we may safely elaborate a general programme for economic analysis. Theoretical economics will consist in the analysis of the equilibria of games. These games will be more or less complex, more or less realistic models reflecting the manner in which economic circumstances affect individuals and individual firms. Such a model, to be appropriate, must in its basic specification of rules and payoffs incorporate those strategic features of technology and trade practice which determine the activity of the various classes of persons and firms making up a total model. Information of this sort will come from industry analyses of the type of Ruth Mack’s study of the Shoe-Leather-Hide sequence (quoted extensively in Lecture 5 of the present work). Econometric data will provide an “experimental check” on models and theoretical analysis, allow decision between competing models, and provide a target at which explanatory effort can aim. Period analysis of games proceeding through time will give a model of economic dynamics (cf. Lectures 5–7 for a rudimentary attempt). Coalition analysis of the von Neumann-Morgenstern type will supplement the general equilibrium-point analysis in much the way in which oligopoly analysis supplements free market analysis in current theory.

We may comment finally on the particular significance of the notion of a “suboptimal” game-equilibrium, cf. Lecture 19, Section 5. The classical arguments offered in attempts to prove the optimality of minimally regulated free competition are, in virtue of their very general nature, arguments which prove that a game theoretical equilibrium (in which all players simultaneously attain individualistic optima) cannot describe an inferior situation. As the existence of model games with suboptimal equilibria shows, however, the result is certainly false, and the arguments therefore invalid. The simplest but most important essence of Keynesianism is already contained in this last remark. Indeed, the Keynesian and the classical theories differ, perhaps most essentially, in that while the classical theories analyze partial optima, the Keynesian theory points out that, at least in a specific economic situation, these par...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- LECTURE 19 Additional General Reflections on Keynesian Economics II. The Price Level in Money Terms

- LECTURE 20 A Model of the Price-Production Cycle

- LECTURE 21 The Hyperinflationary Case

- LECTURE 22 Rates of Exchange

- APPENDIX 1 Remarks on Mathematical economics and Economics Generally

- APPENDIX 2 Estimated Multipliers for Tax cuts of various Forms

- INDEX