The two principal aims of this book are to contribute to restoring the discursive connections linking China’s modern architectural past with the present, connections that were damaged and often broken during the second half of the twentieth century, and to advance understanding of China’s encounter with architecture as a distinct modern art practice. To achieve these aims, this encounter is situated in the broader landscape of modernity in China as it took shape in the first half of the twentieth century by adopting two concurrent perspectives. One looks forwards and backwards chronologically at the history of building in China in an attempt to understand better the interconnections between its ancient and recent past. The other looks around from a specific moment in time before the Second World War at other cultural expressions of modernity in an attempt to locate architecture among other art practices and encounters with modernity.

Architecture, modernity and China

While the subject of architecture, the notion of modernity and the context of China pose no exceptional analytical problems individually, the same cannot be said when considered collectively. Further complicating this problem is the temporal context in which these themes first coalesced: the first half of the twentieth century, a medial epoch bridging the ancient and the modern. Framed by China’s uniquely enduring civilisation, modernity presents some very particular questions, as Jonathan Spence observed: ‘The incredible complexity and durability of Chinese culture pose a challenge to the historian who is seeking elements of the new.’1

With continuous building traditions spanning four millennia, the transition effected by the advent of the architectural profession and its outputs in China from the mid-nineteenth century was more momentous in terms of its impact on established practices and physical forms in the built environment than that which occurred anywhere else in the world. Despite the extent of this transformation in the early twentieth century and the scale of urbanisation in the early twenty-first century, China’s initial encounters with architectural modernity remain relatively obscured. Owing to its particular circumstances – internally and externally – these earlier events and cross-disciplinary discourses have either been overlooked or entirely erased from the historical record.

In an attempt to address such deficiency, this interdisciplinary study is located at the confluence of architecture, modernity and China. Architecturally, the aim is to expand current knowledge about the evolution of the profession in China up to 1949 and thus to contribute to improving China’s comparative under-representation in the historiography of modern architecture globally. In terms of modernity, this exploration aligns itself with recent trends in social theory that have made the case for multiple modernities, and sets China’s architectural experience within these nascent theories, proffering a different way of understanding this experience. In the context of China studies, it aims to contribute to elevating architecture from relative obscurity and to a position of parity with other cultural and artistic practices.

As a conceptual grouping architecture, modernity and China pose and expose particular questions that will be explored throughout the course of the book. However, one particularly dominant problem shadowing this trilogy is the western, or more specifically European, origins of modernity and architecture. The inauthenticity of these two concepts in the Chinese context complicates subsequent analyses and presents a paradox – is it right to examine China using non-Chinese criteria? The answer to this determines the nature of supplementary questions such as whether modernism existed in China and, if not, why not or, if so, what form did it take? Was it a singular hybridised modernism forged from the unique context of China or did this context cultivate multiple forms of modernity? Was it merely a surrogate of western modernism that, once severed from its source, could not survive, or did it assume a genuinely indigenous character that, after 1949, either self-destructed or was reconstituted?

Recognition of the paradox is an essential precondition to exploring China’s en counter with modernity and architecture in the first half of the twentieth century and consequently determines this study’s structure, which forms two parts. The first part focuses on modernity and the second on architecture. China is the overarching context for both. Part I develops a critical discussion of modernity through five analytical themes that approach the subject from different perspectives that consequently inform and contextualise Part II, which concentrates on architecture and, cumulatively, the development of the built environment throughout China which today has more city dwellers than any other country on earth.

Space, time and architecture

The inclusive methodological approach of this study is determined by a number of factors. These include China’s uniquely complicated architectural condition up to the second half of the twentieth century, a response to existing studies in this field, as well as current related theories. Comparative studies tend to focus on individual elements of architectural history in isolation, disconnected from external events and conditions. A lack of thematic inclusivity whether from within or without the field of architecture in China evades the types of questions that make the study of architecture in China distinctive and uniquely challenging.

Methodological inclusivity can be defined three ways: geographically, temporally and architecturally. These criteria were acknowledged by Murphey in his prophetic and aptly titled paper, ‘What Remains to be Done?’ published in 1985 following a conference on the rise and growth of south east Asian port cities. Scholarship in this field has advanced significantly, though less so in the context of architecture. Murphey noted a number of methodological shortcomings including neglect of the ‘comparative and cross-cultural dimension’; the ‘essential [need to] examine Japanese colonialism in Asia, comparatively with the dominantly British scene’; and the need to be less ‘temporally as well as locally specific’.2 These observations are as pertinent in the twenty-first century as they were in the late twentieth century. They also resonate with the scholarly shortcomings identified by Wittrock in Early Modernities, where a better understanding of modernity demands addressing practices ‘not only from outside the European and American sphere but also over long periods of time’.3

Satisfying just one or, as occurs in rare cases, two of these three methodological criteria is unlikely to lead to meaningful or particularly insightful conclusions. For example, in the case of geographic scale, analyses of modern architecture in China that focus solely on treaty ports while overlooking developments in Manchuria are undermined by what they ignore. The same would be true in the case of temporal scale, where attention cast only on the 1930s would be at the expense of preceding or succeeding periods that were informed or were a consequence of this critical decade. And in the case of architectural scale, examining the architecture of either Chinese or western architects separately reveals only fragments of a much richer picture that emerges when they are treated as integral parts of a whole.

Figure 1.1 Shanghai’s Joint Savings Society Building containing the Park Hotel (1934), the tallest building in China until the 1980s, designed by a Hungarian–Slovak architect, László Hudec, for a Chinese client, the Joint Savings Society.

The particularity of China’s modern architectural condition calls for an inclusive approach precisely because nowhere else on earth possesses such multiple architectural experiences today. To make sense of China’s unprecedentedly diverse architectural condition demands an equally plural method of analysis. In no other country did architectural modernity assume such heterogeneity. It was manifest in Asia’s tallest skyscraper, the Joint Savings Society Building (1934), built in Shanghai, designed by a Hungarian–Slovak architect, and funded by a Chinese client (see Figure 1.1). It emerged in the proliferation of modern industrial facilities, such as factories, warehouses,

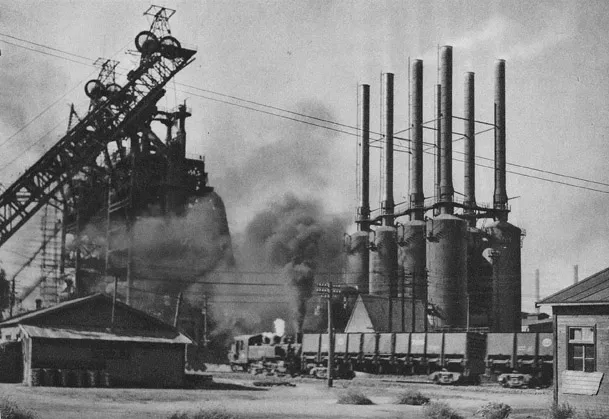

Figure 1.2 Modern industrial buildings at Anshan steel foundry, near Fushun, showing the 350-tonne steel furnace (left) and blowers (right).

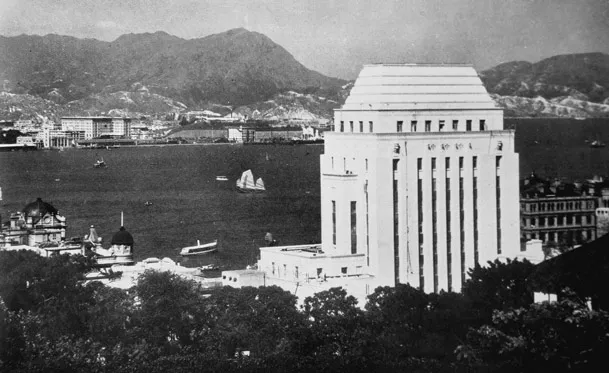

Figure 1.3 The monumental headquarters of the Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation (1935), Hong Kong, designed by George Wilson of Palmer & Turner in a progressive classical style befitting colonial Hong Kong.

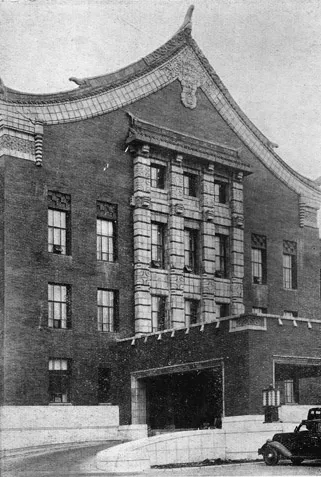

Figure 1.4 The quasi-Japanese design of the Department of Communications, Hsinking (Changchun), Manchukuo.

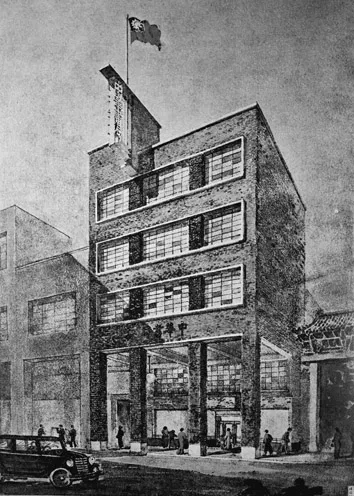

Figure 1.5 The Zhong Hua bookstore (1936), Guangzhou, designed by the University of Pennsylvania graduate, Fan Wenzhao.

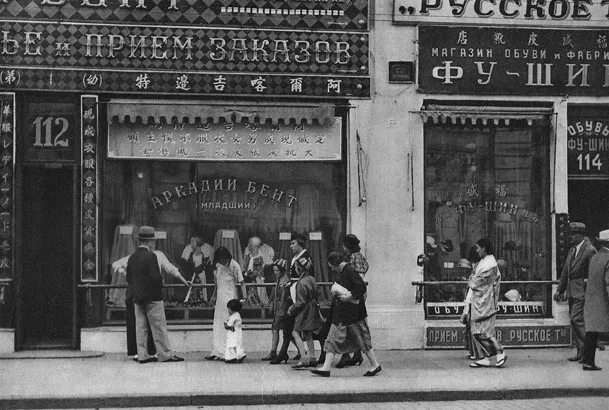

Figure 1.6 The shops and multicultural shoppers on Harbin’s Kitaiskaya Street in the mid-1930s.

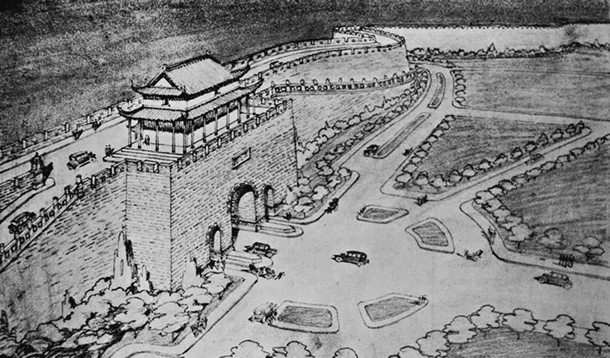

breweries, power stations and steelworks from Fushun to Fuzhou (see Figure 1.2). It was conspicuous in the staid national styles of the colonial and quasi-colonial territories skirting China’s periphery from Dalian to Hong Kong (see Figure 1.3 and Figure 1.4). It could be encountered in the novel commercial enterprises and entertainment facilities, such as department stores, shops, bars and cinemas from Kunming to Harbin that fuelled a budding consumer society, which in larger cities like Shanghai were popular literary settings for China’s modernist writers (see Figure 1.5 and Figure 1.6). It appeared in the new public buildings and infrastructure designed by Chinese and foreign architects in Nanjing and Shanghai and dominated their search for a modern Chinese architectural vernacular (see Figure 1.7 and Figure 1.8). It saturated the modern town plans across Japanese-occupied Manchuria where it reached its apogee in the ‘ultra-modern’ urban planning and architecture of Hsinking, the new capital of Manchukuo (see Figure 1.9 and Figure 1.10).

Figure 1.7 Illustration by Huang Yuyü c.1929 portraying the potential to convert Nanjing’s ancient city walls into a highway for motorcars as part of the city’s modernisation programme.

Figure 1.8 Model of the Mayor’s Office (1934), one of the principal modern buildings in Shanghai’s Civic Centre, designed by Dong Dayou.

Given China’s architectural range...