eBook - ePub

Peasants In Transition

The Changing Economy of the Peruvian Aymara:A General Systems Approach

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Peasants In Transition

The Changing Economy of the Peruvian Aymara:A General Systems Approach

About this book

"The book is an important demonstration of the viability of

General Systems Theory for anthropology. Among the surprising

findings directly deriving from this approach is that the Aymara

transition is a response not to inputs from the industrial

sector, but to instabilities within the traditional Aymara economic

system itself. The Systems Theory principle of the adaptive

value of deviance is the basis for an in-depth analysis of

the emergence of the Seventh-Day Adventists as a power-elite

in many Aymara communities."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Peasants In Transition by Ted Lewellen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

The Physical and Historical Setting

A tourist passing through Acora would hardly notice it. It is but one of several such towns, mere groupings of mud-walled houses and shops, that dot the unpaved section of the Pan American Highway between Puno and Juli in southern Peru. In the dry winter months, roughly from May through September, the town is gray with dust from the wheels of the passenger-and-cargo bearing trucks that pass through at all hours, the leaden monochrome broken only by the colorful skirts and shawls of the women who sell oranges or grapes or apples at the corners of the barren plaza. Saturday the town is enlivened by a cattle market on the pampa, the flat plain, a quarter mile to the north. On Sunday, market day, the plaza is mobbed with sellers and buyers of beans, bicycle parts, school books, plastic shoes and rubber-tire sandals, tools, needles and thread, cheap machine-made cotton shirts and pants, almost anything a campesino might need. But weekdays, except for a few drinkers at the tiny shops that line the square selling sweetened alcohol by the glass, the town is silent and deserted.

In ancient times, before Inca domination, Acora was a commercial center, founded, according to tradition, by Cari, chief of the Lupaca tribe. Today it is what the Spanish call a poblacho--a dirty, insignificant little town.

Acora is the jumping-off place and center of minimal commerce for the community of Soqa, fifteen miles to the east by a road passable for vehicles. Campesinos, who must travel on foot or bicycle, prefer the shorter ten-mile road. In the wet season, when even bicycles are an impossibility, this distance requires a four- or five-hour walk--stops for bread and conversation included--trudging up to one’s ankles in mud and removing one’s pants to ford waist-deep streams. From late June on, it is but two hours by bicycle.

The gutted road runs straight out onto the pampa, and once away from the town one can easily understand why this area is called the altiplano, the high plain. High it is, almost exactly 12,500 feet above sea level. Yet the country here resembles more the hilly deserts of New Mexico than, say, the Rocky Mountains. From the Acora pampa the high mountain chains, the Cordilleras, are not even visible. There is only the plain, bristled with brown ichu grass, stretching away on every side to dry hills, their bases glimmering with the scattered corrugated metal roofs of small communities.

The road runs through two deep and, in winter, almost dry stream beds, past a lake where there is always a flock of flamingos, like a pink island in a pointilist painting, past a primary school, and climbs abruptly so that it is necessary to dismount and walk one’s bicycle. At the top of the hill, an arm of Lake Titicaca appears, but the larger

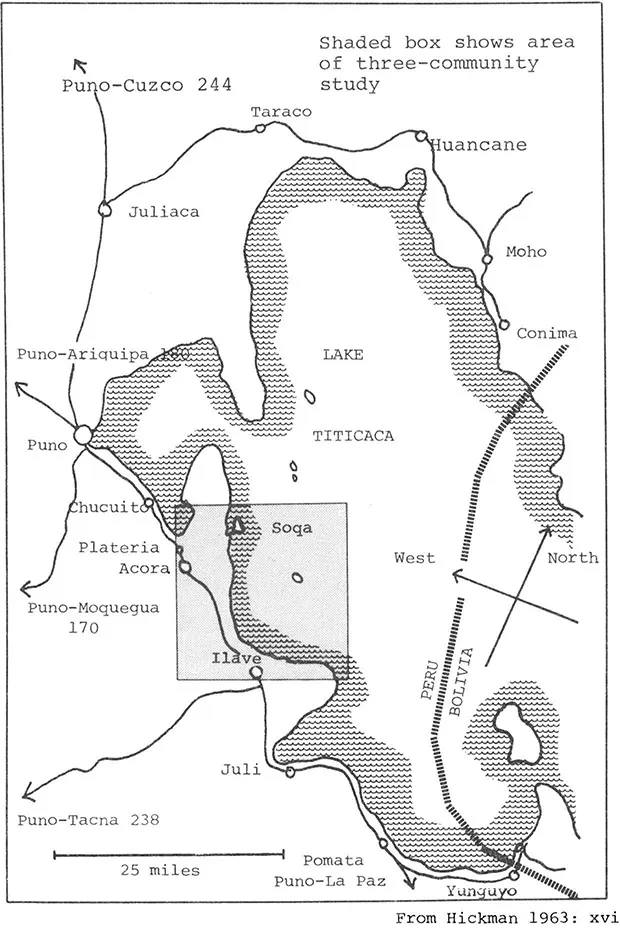

Figure 1.1 Lake Titicaca Basin

part of the lake, in front and to the south, remains hidden behind a high, jagged wall of tortured rock about three kilometers ahead. The road leads down again, past thatch-roofed complexes of houses, past grazing cattle and sheep, past women in red or green skirts and multi-colored shawls; it crosses a valley and rises abruptly up the rugged hill, the path so rocky here that a bicycle must be shouldered and carried most of the way.

Topping the crest, an amazing scene suddenly opens up. The lake appears, the twentieth largest fresh-water lake in the world, a hundred forty miles long, thirty-five miles across, its vast, incredibly blue expanse broken to the north by the Capachica Peninsula and the islands of Amantani and Taquili.

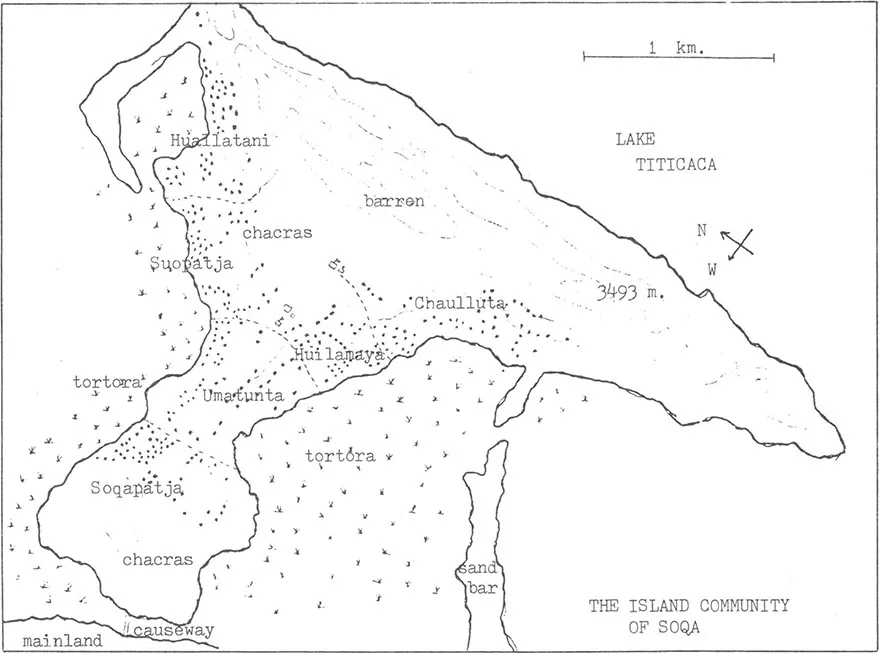

Below, and slightly to the south, the island of Soqa juts into the lake like a huge, roughly-hewn hammer, its “head” a line of high, sheer cliffs, silhouetted by the distant white profile of 21,000-foot Mount Iliampu, in Bolivia on the other side of the lake. From here the island seems a peninsula, but it is a true island, connected to the mainland by a hundred-yard causeway, dry now, but in summer knee-deep under icy lake water.

The houses on the island, about 270 of them—from here but tiny squares—are not centralized but are scattered evenly about the arable part of the land, this side of the cliffs. People and cattle, mere dots in the distance, move among the dry fields. Except for some metal roofs, the view might be exactly the same as that seen by an Inca traveler four-and-a-haIf centuries ago. The island community seems to exist in some perpetual pastoral

Figure 1.2 Soqa

serenity, outside of time, as though nothing has fundamentally changed in millenia.

The image is illusory. Everything is changing.

The socio-economic system of the Peruvian Aymara is presently undergoing a rapid and fundamental transformation. After four hundred years of isolation—enforced from without by persecution, exploitation, and bigotry, and from within by suspicion, hostility, and fear--the Aymara are moving from their closed agricultural communities into the wider world of the money economy, a world characterized by circular migration to the coast, increased contact with once remote mestizos, entirely new local government structures, and such peculiar religious changes as the development of a minority Protestant elite.

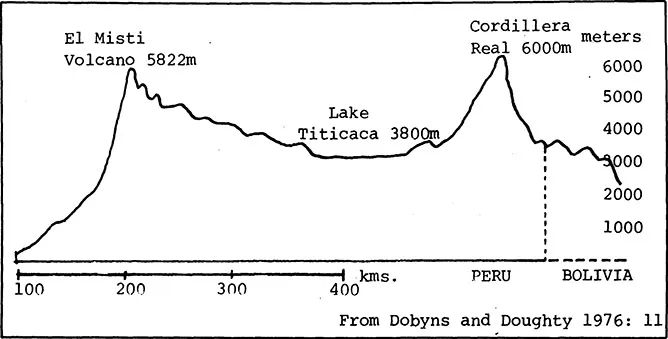

That change should arrive so late is not surprising, given the geographical and cultural barriers which have long cut off the Aymara from the mainstream of Peruvian history. The Andes in the region of Lake Titicaca, on the border of Peru and Bolivia, hardly resemble North American conceptions of “mountains.” Rather, they are like an enormous lump, over four hundred kilometers across, rising dry and virtually vegetationless from the Pacific deserts to a relatively level plain, then dropping precipitately on the eastern side, in a series of jagged peaks and lush valleys, to the vast jungle below. On top of this “lump,” extending along either side, are two mountain chains, the Maritime Cordillera to the west and, to the east, the awesome Cordillera Real. Between these two towering white walls lies the altiplano, stretching hundreds of miles south of Cuzco into Bolivia, a dry, barren region of pampas, hills, and plateaus, at an altitude of 12,500 feet (the level of the lake) and up.

Figure 1.3 Profile of the Andes in the region of Lake Titicaca

Little grows naturally here: the pampas are covered by clumps of tola and yareta bushes and course ichu grass, poor forage for any but indigenous llamas and alpacas. There are essentially two seasons, rainy and dry, roughly winter and summer. Hickman (1971: 5) calculated a 45° F. annual mean temperature, with a range of 40° to 65° for twenty-four hours for the planting months of October to April, and 35° to 65° for the May to September dry months. It can get colder; I have seen snow, several inches deep, stay on the ground for days in late August and early September.

The population of this area, specifically in the department of Puno, reflects patterns long outmoded for Peru considered as a whole. Whereas the nation is now almost 60% urban—a statistic reflecting the internal colonialism of Lima, which drains both human and physical resources from the rest of the country--Puno remains a mere 24% urban, and many of these “urban” residents live in tiny pueblos. For the district of Acora, in which lie two of the communities of this study, out of a population of 28,963 only 1,510 are “urban;” the other 95% are rural peasants, living in numerous small communities, mostly mere collections of houses with perhaps a school but lacking a plaza or even a store (ONEC 1972: 2, 46, 60).

The department of Puno’s total population of 779,564 (ibid: 2) is large, considering that the vast majority of these people are crowded about the shores of the lake, where agriculture is so intensive that most fields are never allowed to go fallow, and in many areas there is such a scarcity of grazing land that cattle are tied in the potato fields and fed lakeweed and tortora. A tall reed that grows profusely in the lake, tortora furnishes not only cattle food, but is eaten by campesinos during the hard months before harvest and used to thatch roofs and to construct balsas, canoe-shaped reed boats, so familiar from travel posters of Lake Titicaca.

There is a rigid class division between Indian campesinos and mixed-blood mestizos, the latter comprising the large landholding, entrepreneurial, industrial, and urban class which has, for centuries, been in a position to dominate and oppress the peasant class. Intermediary between these two groups are the cholos, a term with derogatory connotations, but the only term available. These are people who have repudiated their campesino origins and have assumed mestizo dress, language, and values. Despite their reputation for being “campesinos on the make,” cholos form a class of often ambitious entrepreneurs—store owners, small factory owners, truck drivers, and contrabandistas—that is extensively involved in the economy of the altiplano.

The peasants, in contrast, have not been so involved, at least until very recently. Growing for their own families’ subsistence, with no specialization for market sales, Aymara peasants have only minimally participated in the national economy. Their closed, unvarying life, tied to the yearly agricultural cycle, was the Aymara pattern of culture for many hundreds of years.

Present-day Aymara are the direct descendants of a number of tribes that inhabited the lake region since pre-Inca times. The largest of these were the Colla and Lupaca, who were deadly rivals. When Viracocha began expansion of the Inca empire about 1430, chiefs of both these tribes recognized the power of this new military force from the north, and tried to ally themselves with it. Viracocha chose alliance with the Colla, stimulating an attack by the Lupaca which killed the Colla chief. When Viracocha arrived to render punishment, the Lupaca quickly made a pact with the Incas. Thus the larger part of the early conquest of the Titicaca Basin was accomplished without warfare on the part of the conquering empire.

Chucuito, the Lupaca capital, thus became the capital of Collasuyu, the southeastern and largest of the four quarters into which the Inca empire or Tahuantinsuyu (literally, “Land of the Four Quarters”) was divided, an area extending from the Titicaca Basin over most of Bolivia and into northwest Argentina and northern Chile.

Even under the yoke of the Inca, the Aymara commenced the pattern of violent rebellion that characterizes them to the present day. Though supposedly already “conquered” by peaceful means, the Co11a and Lupaca had to be forcibly reconquered twice. Later, during the reign of Huayna Capac (1493-1527), Aymara troops were trusted enough to be permitted to fight in the Inca armies under their own leaders. In the Inca civil war, the Aymara sided with Huascar against the briefly victorious Atahualpa.

In the early stages of the Spanish conquest, the Titicaca region was reconnoitered by an important military expedition under Diego de Almagro, but the Spaniards went on to explore south, later to return to attack Cuzco and embroil themselves in a series of civil wars, leaving the Aymara to their own devices. With the defeat of Manco Inca--the puppet ruler who took charge of the Inca forces and turned them against his Spanish masters--the Lupaca asserted their independence by attacking their age-old enemies, the Colla. The latter requested Spanish aid, thus paving the way for easy Spanish domination of the area.

For centuries during which civilizations rose and fell and conquest followed conquest, peasant culture remained relatively unchanged. The basic Andean social unit, the ayllu—a group of kin that held land in common—persisted intact. Such continuity was hardly contested, except by disease, during the years that immediately followed the defeat of Tahuantinsuyu. The Spanish abolished the Inca religion without replacing it with Christianity, so many Indians simply reverted to pre-Inca religious patterns. The energies of the conquerors were expended in internecine wars, gold hunting, and establishing cities, so they maintained authority in remote rural areas only through local Indian leaders, thus permitting a lesser cultural unification of Andean populations than had been the case under direct rule by the Incas.

This situation lasted only until 1572, when Viceroy Francisco de Toledo defeated the last remnants of Inca opposition, finally permitting a transition from “conquest culture” to true colonial culture. Since the economic system that financed the viceroyalty was based on Indian labor and tribute, the history of this era is one of brutal, but routine, exploitation and oppression.

Toledo was the fifth Spanish viceroy of Peru, but the first strong leader, and the first to try seriously to centralize authority. In their rural isolation, Indians were vulnerable to all sorts of depredations by the ravenous Spanish. Supposedly to protect them, as well as make their religious conversion easier, Toledo had the Indians gathered in urban centers called reducciones, where they were over-seen by administrative officials called corregidoresmight be claimed for the. This move made it easier for the Spanish to seize deserted lands. Whatever good intentions might be claimed for the reduccion program, little in that direction can be claimed for Toledo’s version of the Inca mita, Spanish-Colonialism’s “most deadly dimension, after Old World diseases, for the Peruvian Indians” (Dobyns and Doughty 1976: 100). According to legal statutes, the corregidor was to impress one seventh of the adult male Indians of his region into the mita system of forced labor. For the altiplano, mita came to signify mita de minas, forced labor in the silver mines at Potosi or Carabaya and, later, at the mercury mine at Huancavelica. LaBarre (1948: 31) estimates that over 14% of the Aymara were in forced labor in the mines at any one time. The mita de minas was virtually a capital sentence: there was a death rate of two out of three mitayos at Potosi where workers were forced to live chained together in the shaft for five days, without seeing daylight. Work was supposedly for a year, but one could seldom accomplish production quotas in a year, even with wife and children helping. Yet it was not Potosi, but Huancavelica that was called the “mine of death;” the high grade mercury ore was so poisonous that even families living near the mine suffered the effects. It has been estimated that the Indian population of Chucuito shrank by two-thirds between 1628 and 1754 because of the mitas (Dew 1969: 21).

The Church offered little opposition to such horrors. Contrary to present belief, most priests were not missionaries and had little to do with uprooting idolatry or converting natives. Rather, most of them served Spanish populations, living in cities or attaching themselves to wealthy encomenderos. There were, however, a few, mainly Jesuits, who actively protested against the exploitation, a transgression which--along with becoming too wealthy and influential themselves--got them expelled from all America in 1767. This left the Indians of the altiplano with no protectors. Added to the mita, to virtual sla...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 THE PHYSICAL AND HISTORICAL SETTING

- 2 A SYSTEM IN TRANSITION

- 3 LAND, POPULATION, AND POSITIVE FEEDBACK

- 4 OPTIONS AND STRATEGIES

- 5 THE CHANGING SOCIAL STRUCTURE

- 6 NEW FUNCTIONS FOR OLD RELIGIONS

- 7 THE ADVENTIST ELITE

- 8 TOWARD A NEW STABILITY

- 9 PEASANTS IN TRANSITION: TOWARD A GENERAL MODEL

- APPENDIX

- Bibliography