![]()

Part I

The Drivers of the Informal Economy

![]()

1 Tax Morale and Informality in Post-Socialist Contexts

Diana Traikova

Introduction

Undeclared work (informality) is defined as paid work, which is legal in other aspects other than it is not reported to the tax-, social security- and/or labour law authorities (Polese & Rodgers, 2011). While it gives (a short-term) competitive advantage to the given individual or firm, it is generally seen as a problematic phenomenon, because it undermines the solidarity principle of state budgets, and disadvantages rule-obeying tax-paying citizens and companies.

In their review, Williams and Franic (2016) describe two major approaches aiming to tackle undeclared work through direct controls. The deterrence (stick) approach aims at increasing the costs and diminishing the benefits of participating in the informal economy. This includes increasing the actual and perceived likelihood of detection and sanction of tax law infringement, signalling that tax evasion is a ‘bad behaviour’. The incentives (carrots) approach seeks to increase the benefits of participating in declared work in an attempt to ‘seduce’ or ‘bribe’ individuals into working formally through offering benefits, which are not accessible to the informal agents. This approach is not so widespread in post-communist countries, where it is rather the exception. There is also a third approach, which is based on indirect controls, resulting in self-regulation, motivated by the intrinsic desire of taxpayers to work formally. It is seen as the most cost-effective way for tackling undeclared work, because no expensive control measures and enforcement are needed. Instead, the focus is on normative appeals, guaranteeing redistributive and procedural justice, social fairness and tax education. There is evidence from field experiments for high effectiveness of the intrinsic motivation for tax compliance (Dwenger, Kleven, Rasul & Rincke, 2016; Torgler, 2002). Williams and Franic (2016) found that in Bulgaria, a traditional post-communist country, there is a low association between undeclared work and risk of detection and penalties, but strong association between tax morale and the participation in undeclared work. Their definition of tax morale is based on the mismatch between the formal and informal institutions in the sense of ‘rules of the game’ (North, 1991). Also Williams and Vorley (2014) advocate that this institutional asymmetry between formal and informal rules is a key to understanding the underperforming entrepreneurship in transition countries.

Although it contains the word ‘morale’, this definition of tax morale is not precise enough to bring more concrete insights about the ethical motivation of individual decision makers, when they intentionally choose to under-report their work. The current contribution suggests that it might be useful to observe the motivation for informal work through the prism of ethics and seeks to develop a tentative new way of measurement of tax morale. For this it adopts an aggregated theoretical model, integrating individual and situational motivational factors and reflects through it on diverse aspects of informality in post-socialist societies.

Why should we deal with ethics? Regarding the empirical evidence from above, intrinsic self-regulation appears as a policy cost-effective option for tackling undeclared work, but it is feasible only if people do not see informal work as legitimate. If we want to understand informality (which is used here as synonymous of undeclared work), we need to understand how people legitimate it (Webb, Tihanyi, Irland & Sirmon, 2009). For this we need to understand if citizens as potential taxpayers see informality in its different degrees as something that is wrong, or not. Ethics is about recognizing good and evil, distinguishing between good and bad, right and wrong (Ferrell, Gresham & Fraedrich, 1989). Moral judgements inform the choices (among others) of employers, employees and unemployed. When they flag undeclared work as ‘wrong’, the self-regulation mechanism will hit the ‘brakes’ and the individual will most likely try to avoid this behaviour because it will cause him/her moral disutility. In this way, moral judgements will shape the attitudes of individuals as economic actors and should influence the set of business opportunities, which will be recognized as feasible and worth exploiting under the current post-socialist system in a particular society.

The author could not identify studies proposing to tackle post-socialist informality in this way, most studies on tax morale stem from developed economies. Also, a solid body of ethical decision-making literature was found, which gradually developed and fine-tuned a theoretical model of ethical decision making for the purposes of the marketing research. Although not tailor-made for the study of undeclared work, the principles of moral judgements and choice are universal and can easily be applied to the case of informality. The paper proceeds with a short overview of the core terms of this literature, in order to introduce the reader to an integrated model of ethical decision making.

Literature Review of Relevant Ethical Terms and Theories

Ethics comes from the Greek ethos, meaning character. Morality comes from the Latin moralis, meaning customs or manners (Thiroux & Krasemann, 2012). In philosophy, however, the term ethics is also used to refer to a specific area of study: the area of morality, which concentrates on human conduct and human values. A moral issue is present where a person’s actions, when freely performed, may harm or benefit others (Jones, 1991). Undeclared work harms the overall society by depriving it from tax income for financing public infrastructure and services. It also benefits the individual directly in the short term because it increases the immediate disposable income of the entrepreneurs/employees, while not excluding them from using the e.g. public infrastructure. When one also considers the accompanying aspects of work safety, child allowances, diminished pension income and other well-known consequences of informality, it is evident that it clearly has a moral component. A moral agent is a person who makes a moral decision, even though he or she may not recognize that moral issues are at stake (Jones, 1991). This could be the entrepreneur deciding to work on his or her own account without paying (part of or even the full) insurance and taxes, a firm manager adopting the envelope wages as a common business practice or a potential employee, who is considering to take up such employment, not being aware that his/her pension later will be dramatically diminished. In developed societies, the widely accepted moral rules are to a high extent embodied in the written laws. As the literature on post-socialist informal employment well illustrates, this is not the case in transitional societies. Here an ethical decision is one which is morally acceptable to the larger community—a definition similar to the one used by Jones (1991) and adopting the legitimacy idea suggested by Webb et al. (2009). But how do moral agents arrive at their moral judgements? How do they decide what is good and what is bad? For this we turn to the moral philosophy, which has crystalized two main ways of reasoning: by looking at the consequences of a certain action, and by aiming to stick to generally valid moral ‘rules’. In order to account for the contextual and individual particularities, the situational and personal characteristics of the moral agents (potential taxpayers or evaders) should be considered. Each of these will be shortly introduced.

Teleological (Consequentialist) Moral Philosophies

In this moral view, all that counts for the goodness or badness of an act are the consequences. If there are several ways to solve an ethical problem, the moral agent should choose the one that leads to the best consequences (highest good and minimum bad). This sounds simple, but goes with some complications. We need to be aware that humans have only limited cognitive capacity and no perfect information. This means that most likely only a subset of the possible consequences will be identified, and maybe some of them will be anticipated in a wrong way. Differences in ethical decisions may be traced, in part, to differences in the set of perceived alternatives and their consequences. Another complication is the lack of clarity when it comes to whom the moral agent will take as a reference: the best for the self (moral egoism) or the best for all, for the society as a whole (utilitarianism). Also, it is very costly to investigate and estimate the consequences for the others without knowing their situation, preferences, needs, priorities, etc. In contrast, teleolologists believe that each moral act may look different, depending on the particular situation and context. They are against absolute rules. For example, telling the truth about tax evasion might be ethical in one situation, but not so in another, where this will lead to e.g. shutting down the business of a friend, who is the single bread winner for his family.

Deontological (Non-Consequentialist) Moral Philosophies

Deontologists are not concerned with the consequences, but aim to stick to some set of true and valid universal moral rules, believing that they are a warranty for ethical decisions. Every individual has a different set and ranking of rules she/he has accepted as worth obeying. These deontological norms mirror the personal values for moral behaviour and are contingent on the experienced socialization and the life course to date. For example there are the rules not to kill, to be honest, not to steal, not to cheat, to treat people justly, etc. (Hunt & Vitell, 2006). These can be universally valid norms or community-specific rules, which have proven efficient in governing e.g. the community life. It would be interesting here to probe for them in relation to tax compliance.

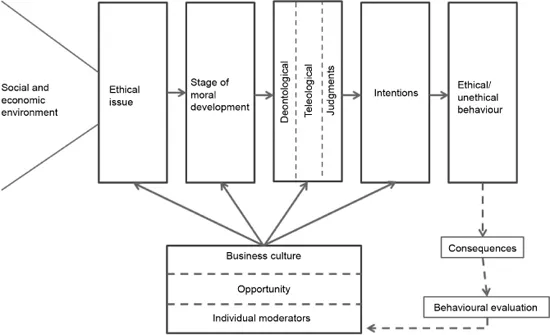

Integrated Model for Predicting Moral Decisions

Rational ethical decision making is only possible after an ethical dilemma (issue) has been recognized. There are several popular ethical decision-making models in the literature describing the solution of such dilemmas, which are partly overlapping. They have been reviewed in Ferrell et al. (1989). To extract the maximum explanatory power from each of them, these authors suggested aggregating the models and including only their non-redundant components. The building blocks for this consist of Kohlberg’s (1969) famous Model of Moral Development, Ferrell and Gresham’s (1985) Contingency Model of Ethical Decision Making and Hunt and Vitell’s (1986) General Theory of Marketing Ethics. The result of this aggregation is shown in Figure 1.1 below.

Although not really new, this framework has remained unnoticed by the scholars of informality and tax morale. In the face of lacking clear understanding of what is the key of legitimation of undeclared work, it delivers detail-rich and relevant-for-the-practice insights, which are for now scarce in the field.

Figure 1.1 Integrated model of ethical decision making in business

Observing Post-Socialist Informality Through the Integrated Model Lens

Every conscious business decision is embedded in a context. People live in societies and the rules for interacting and behaving there are installed over time in a way that facilitates the more or less smooth and sustainable functioning of the particular society. In transitional contexts, this adju...