Water is essential to life and rivers are one of the main sources of water. Civilizations such as those in China, Egypt, Babylon and India have developed along and thanks to famous rivers: the Yellow, Nile, Euphrates and Tigris and Ganges respectively (Di Baldassarre et al., 2013a; Liu et al., 2014). This is because the floodplains of these rivers constitute very favourable areas in terms of geographical location and environmental conditions to settle in, even though they are also prone to flooding (Junk et al., 1989). Today still, floodplains remain attractive places to live and settle, places where societies can practice agriculture and find means of transportation for trade and economic growth (Di Baldassarre et al., 2013a). Yet, living in floodplains comes with risks. Flooding and the relocation of river channels by erosion and deposition may cause damage to agricultural lands, crops, homes, roads and buildings. When deciding whether to live in a floodplain area, people therefore evaluate the chances of this damage to occur, including the extent of flooding they may experience, and make a decision whether to mitigate the risks or live with them.

As the number of people living in floodplains continues to increase (Lutz, 1997), so do the risks societies living in floodplains face. Flood risk can be defined as a combination of the probability of a flood event and its potential adverse consequences, or risk = probability * consequences (Di Baldassarre et al., 2009; van Manen and Brinkhuis, 2005). Vulnerability is the degree to which societies are susceptible to destruction by hostile factors (Şorcaru, 2013) and includes societies’ responses to risk as well as the risks themselves. Flood risks are not usually equally distributed across societies, with some people having a better ability to cope than others (Masozera et al., 2007; Di Baldassarre et al., 2013a,b). Societal responses to hazards in floodplains can include demographic shifts (such as resettlements and migration), governance measures (such as flood control, disaster management), land use changes, livelihood changes (such as a change in occupation), and technical interventions in the physical layout of the floodplain, e.g. homestead mounds, ditches and dikes. Such responses may in turn influence the future behaviour of rivers and the chances of floods; they may for instance exacerbate flood risk rather than reducing it, thus increasing the vulnerability of a society (Milly et al., 2002; Di Baldassarre et al., 2010).

Such dynamic interactions between society and rivers in floodplain areas have become a topic of research interest (Di Baldassarre et al., 2013a,b). Studies for instance look at how constructing flood control measures or changing land-use patterns alter the frequency and severity of floods. As Di Baldassarre et al., (2013a,b) argue, however, the dynamic interactions and associated feedback mechanisms between hydrological and social processes remain unexplored and poorly understood. Indeed, there is a lack of understanding on how and to what extent hydrological processes influence or trigger changes in social processes and vice-versa. To address this gap in knowledge, Sivapalan et al., (2012) have proposed the new science of socio-hydrology. Socio-hydrology proposes to study the two-way coupling of human and water systems with the aim of advancing the science of hydrology for the benefit of society (Montanari et al., 2013). This research takes inspiration from and aims to advance socio-hydrology. It focusses on the two-way interactions between society and water in the Jamuna floodplain in Bangladesh.

1.2 SOCIETAL RELEVANCE AND SELECTION OF CASE STUDY

More than 100 million people in the world are affected by floods every year. Flooding is the most damaging of all so-called natural hazards, causing about fifty percent of all deaths from disasters worldwide (Ohl and Tapsell, 2000; Opperman et al., 2009). Increases in population and demographic expansion enhance pressures on river floodplains, resulting in increased flood probability and hence risk. In the years 2011 and 2012 alone, about 200 million people were affected by floods with a total damage about 95 billion USD 2012 (Ceola et al., 2014).

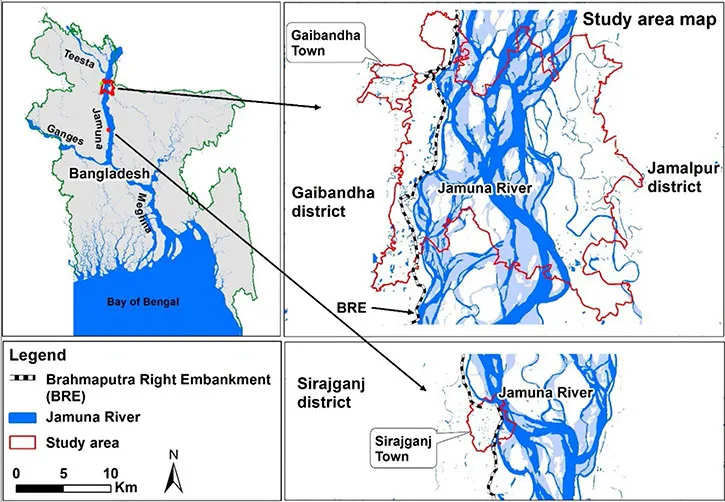

Bangladesh is among the countries that is notoriously prone to flooding because of its location at the confluence of three mighty rivers: the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna. Indeed, Bangladesh is one of the largest deltas in the world (Mirza et al., 2003). The combined flows of the three rivers come together in the Bay of Bengal through the Lower Meghna River, culminating in a total of 1 trillion m3/year of water and 1 billion tonnes/year of sediment (Allison, 1998). In addition, there are hundreds of medium and small tributaries and distributaries flowing through the country. More than half of the country consists of floodplain areas (Tingsanchali et al., 2005; Nardi et al., 2019). About 10% of the total area of the country is less than 1 m above mean sea level and one-third is under tidal influence (Ali, 1999). 92.5% of the combined basin area of Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna lies outside of the country, putting Bangladesh at the mercy of upstream water uses and management decisions. With 80% of the annual rainfall occurring in the monsoon (June-September) across these river basins (Mirza, 2002), runoff is concentrated in just a few months. Very often, the peak volume exceeds the capacity of the river channel networks, resulting in severe flood events. Such events happened in 1954, 1955, 1974, 1987, 1988, 1998, 2004, 2007 and 2017 (FFWC/BWDB, 2018). The most severe flood events occurred in the last 50 years. In 1988 and 1998, about 61% and 68% respectively of the country was inundated by riverine flooding (Penning-Rowsell et. al, 2012). While the northern part of Bangladesh is vulnerable to riverine flooding only, the southern coastal part is mainly vulnerable to flooding due to storm surges (Tingsanchali et al. 2005). There are several other factors which make Bangladesh prone to flooding: very low floodplain gradients, the reduction of stream channel capacities due to the building of infrastructures such as dykes and polders, and excessive siltation of river beds (Rahman, 1996). In addition, Bangladesh is experiencing subsoil compaction and iso-statically induced subsidence, which further increase flooding (Goodbred and Kuehl, 1999, Sarker et al. 2003).

Bangladesh is a very densely populated country with more than 140 million of people (964 persons per km2). Around 80% of the total population lives in floodplain areas and most of them mainly depends on agriculture (BBS, 2013). Flooding and riverbank erosion severely impact agriculture through the loss of land and crops. The 1988 flood affected about 73 million people (Penning-Rowsell et. al, 2012), among them about 45 million people were displaced and about 2,000-6,500 died. The 1998 floods caused about 1,100 deaths and displaced about 30 million people (IOM, 2010). In the most recent severe floods of 2017, about 62,000 km2 (about 42% area of the country) was inundated (FFWC/BWDB, 2018), affecting about 8.3 million people and causing 147 deaths (NDRCC, 2017). Around 700,000 houses were severely damaged and 0.7 million hectares of cropland affected (NDRCC, 2017).

River channels and flooding patterns are changing every year. The extremely poor people who are living on the so-called chars - islands in the big rivers - are most exposed to and affected by flood hazards and riverbank erosion. During severe flood events, they often have to migrate to nearby areas. They may have to move permanently because the river islands they lived and farmed on simply disappear. During 1981-1993, about 0.7 million char-land dwellers were displaced. Half of them were from chars in the Jamuna River (FAP 16/19 1993).

Successive governments have developed a range of measures to protect agriculture and populations from floods (Sultana et al., 2008). However, the country encounters and has encountered difficulties to mobilize enough funds to adequately protect all areas. This is why the government decided to prioritize some areas to be protected first. After the severe floods in the years 1954 and 1955, the government for instance decided to construct an embankment along the west bank of the Jamuna River, called the “Brahmaputra Right Embankment (BRE)”. The main reason for this choice was that the duration of the flood was longer on the west bank than on the east bank, something that is caused by the average land elevation being lower along the west bank than along the east bank (Sarker et al., 2014). In addition, crop production was higher along the west bank, which is why total damage on the west bank was also higher. In addition, the river has been eroding and migrating westward since 1830 (Coleman, 1969). The BRE was constructed in the 1960s to limit flooding in an area of about 240,000 ha lying on the western and southern sides of the Brahmaputra-Jamuna and Teesta rivers respectively and to increase the agricultural production of that area. The construction of the embankment started in 1963 and was completed in 1968 at a cost of about BDT 80 million (~16.7 million USD) (CEGIS, 2007). This was the first major intervention to protect people and lands from flooding in Bangladesh. In addition to such physical interventions, the government also set up a programme to predict flooding since 1972 (FFWC/BWDB, 2018) and riverbank erosion since 2004 (CEGIS, 2016) and disseminate the results to the affected population, to increase their ability to prepare for and cope with flooding and riverbank erosion.

A scoping study has indicated that the impacts of embankments are not necessarily and always positive (Burton and Cutter, 2008; Opperman et al., 2009). To date, no studies have been done to better understand the relation between social and hydrological processes along the main floodplain areas of Bangladesh. The few studies that do exist aimed to understand these relations in the coastal region of Bangladesh. These have shown how human interventions such as upstream diversion and coastal polders significantly contributed to the variation in water salinity, tidal water level and flooding in the southwest coastal region of Bangladesh (Mondal et al., 2013, Ferdous, 2014). Other studies (e.g. Walsham, 2010) show that hydrological changes in turn shape patterns of human settlements and trigger migration. However, these studies always look at one or the other side of the interplay between hydrological and social processes. The dynamic interactions and feedbacks between social processes and hydrological processes remain underexplored. Studying these is a new academic field, one that is particularly relevant in a dynamic delta such as Bangladesh. The purpose of the present study precisely is to delve into these interactions and feedbacks, with the purpose to better understand the dynamic relations between social and hydrological processes in the main floodplain areas of Bangladesh. The ultimate aim of producing a better understanding is to help developing better protection systems, and reduce the damage and suffering caused by flooding and riverbank erosion. The hope is that improved understanding of these interactions between social and hydrological processes using a coupled two-way dynamic conceptual model will strengthen our capability to design suitable future interventions and/or suitable adaptation options in Bangladesh.

The research was carried out in a case study area that includes rural areas in Gaibandha and Jamalpur districts and two urban areas Gaibandha town and Sirajganj town (Figure 1.1). The total surface of the study area is about 550 km2 and the total population is approx. 0.6 million (BBS, 2013, BBS, 2014a). I have chosen it as my case study area because of my familiarity with it: I have more than 10 years of professional experience working here as a water engineer charged with flood forecasting, flood management and training residents on using flood forecasts. During my professional work, I observed how difficult it is to take decisions to manage floods in this region. Hence, I am directly motivated to and interested in helping decision makers to do flood management and take flood management decisions. More detailed descriptions of the case study areas are presented in chapters 2, 3, 4 and 5.

1.3 CONCEPTS AND THEORIES

Water resource studies in floodplains were until recently dominated by hydrologic studies for water resources planning, flood management etc. aimed at informing engineering interventions. In recent years, since the 1990s, hydrologic studies have started to integrate social variables and data in their analysis (McKinney, 1999). This was in recognition of the fact that ignoring ‘the human factor’ in dealing with and making decisions about water and rivers was dangerous (Sivapalan et al., 2012). Nowadays hydrologists are gradually entering into and developing the field of socio-hydrology, which sets out to advance understanding on how and to what extent hydrological processes influence or trigger changes in social processes and vice-versa. In traditional hydrology, human factors are assumed as external forces or taken as the given, stationary context in which water cycle dynamics play out (Milly et al., 2008; Peel and Blöschl, 2011). Socio-hydrology instead aspires to include humans and societal dynamics and processes as internally related to water cycle dynamics. The aim of socio-hydrological studies is to observe and understand the mutual relations and dependencies between societies and rivers in order to better predict future paths of co-evolution of coupled human-water systems. This approach is different from the science of integrated water resources management (IWRM). While IWRM is also about interactions between humans and water, its approach is scenario based. It does not account for the dynamic interactions between water and people, which may be unrealistic for long-term predictions. Understanding such coupled system dynamics is expected to be of high interest to governments who are dealing with strategic and long term water management and governance decisions (Sivapalan et al., 2012).

Studies using a socio-hydrological approach in floodplains have proliferated rapidly in recent years (Di Baldassarre et al., 2013a, b, 2015; Viglione et al., 2014; O’Connell and O’Donnell, 2014; Chen et al., 2016; Ciullo et al., 2017; Grames et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017; Barendrecht et al., 2017). In their review paper, Wesselink et al., (2017) distinguished the use of two different methodologies for the study of floodplains in sociohydrology: (1) a narrative representation of the floodplain’s socio-hydrological system based on qualitative research and (2) a characterisation of the development of the floodplain through the use of a generic conceptual model of human–nature interactions which is expressed in terms of differential equations. The first approach is importantly led by experiences and knowledge of local inhabitants and experts about their histories of living with floods. Sometimes it may also include historical statistical data to see trends. These studies are useful for capturing historical patterns in the co-evolution of river dynamics, settlement patterns and technological choices (Di Baldassarre et al., 2013a, 2014). The second approach also starts with a narrative understanding of the situation, but uses this to distin...