1 New frontiers and objectives of financial regulation

1 Financial exclusion: definition, causes and size of the phenomenon

The subprime crisis highlighted the problems linked to a system that considered financially excluded people only as a source of speculative profit. Generally, only not-for-profit alternative financial operators were addressing these issues, ignored by mainstream financial institutions and related literature.

Financial exclusion is commonly referred to as the condition of no or limited access of low-income working-age adults to mainstream financial services that are appropriate to their needs.1 The Commission refers to financial exclusion as ‘the process whereby people encounter difficulties accessing and/or using financial services and products in the mainstream market that are appropriate to their needs and enable them to lead a normal social life in the society in which they belong’.2 In fact, the inclusion/exclusion is generally evaluated by four criteria: access (in terms of costs and proximity), quality (availability of a variety of products targeted to clients’ needs and treatment), usage over time and impact/welfare (changes in clients’ lives linked to the use of financial services).3 The causes of lack of access are various.4 A first group of causes can be referred to self-exclusion: low-income people tend to avoid banks because of the idea of being inadequate for bank accounts (generally banks having quite strict requirements in terms of minimum deposit balance and credit history, high fees, etc.) or because of resentment caused by previous bad experiences with banks (also in their home countries in the case of migrants).

A second group relates to banks’ decisions based on economic-business motivations and might consist, for example, in too low minimum account balances or too high fees or too demanding client profile (e.g. in terms of income, credit scoring, employment, collateral or documentation required). Moreover, products offered might not be appropriate for low-income people’s financial needs and typical standardized procedures be unable to understand their risk profile, repayment and business chances and need (see Chapters 4, §5; 6, §2.b).

A third group of causes of financial exclusion are embedded in some societies in general: many clients might be discriminated against based on gender, religion, language, social position or age or might not be able to access and understand bank products and services because of education or geographical limitations.

In many economically advanced countries (EACs), bank branches are often located close to poor clients (in poor boroughs) but products and marketing techniques appear inadequate to serve them.5 For instance, the majority (57.5%) of unbanked U.S. households in 2013 reported as reasons for financial exclusion not having enough money to open an account or not meeting the minimum required balance (the main reason for 35.6%), high or unexpected fees (30.8% of unbanked, the main reason for 13.4%) and distrust/dislike of banks (34.2%, the main reason for 14.9%).6 Consequently, low-income people tend to use alternative financial services (such as pawn shops, payday lenders, cheque cashers, money transfers, credit cards and prepaid debit cards) that are often more expensive than normal banking ones (see also Chapter 4, §5.b).7

The majority of unbanked or underserved people belong to particular societal groups, such as low-income people, unemployed or people with non-regular and unstable jobs, low financial literacy, young people, ethnic minorities, living in suburbs or agricultural areas.8 In Europe, in particular, financially excluded people are mostly unemployed, minorities or migrants, people with disabilities, the elderly (over 65), young people and women.9

With special reference to credit services, studies highlight credit markets’ imperfections, which make the optimal equilibrium between demand and offer unreachable, with the result of a contraction in credit availability.10 Banks, in fact, in their decisions about loans to their clients are influenced not only by the interest rate they can charge but also by the level of risk, which because of asymmetric information is itself affected by the interest rate charged. In fact, banks cannot have complete information about loan applicants (especially when they are unemployed, immigrants or without valuable possessions as security) and consequently charge higher interest rates in order to hedge such risk. This might, on the one hand, attract high-risk borrowers (adverse selection problem: the ones willing to pay a high interest rate also expect higher profits and therefore are able to accept greater risk) and, on the other, has a negative effect on borrowers’ incentives (moral hazard problem: the higher the interest rate, the greater the incentives on borrowers to engage in risky but more profitable activities). Consequently, the demand corresponding to the optimal level of interest rates is higher than the offer and the bank will deny loans even to creditworthy borrowers (typically of lower income).11

The market can also be affected by high transaction costs (that might be due to institutions’ and market infrastructures’ deficiencies): providers are thus unable to reach economies of scale and scope and they charge high fees and costs, therefore excluding poor households as clients.

Finally, the first movers face the dilemma of bearing all initial costs while newcomers can easily adopt their model once proved to be successful. Especially in a field not involving large sums of money and therefore less remunerative than others, this fact might reduce the number of providers interested in entering the market unless they receive some kind of external support even in the form of coordination among participants (see Chapter 7).12

The lack of access to formal financial services does not necessarily imply the lack of any financial instrument or the need of it. On the one hand, especially in EACs, people often do not ask, for example, for credit because they think not to need it (having internal resources or lacking a viable projects; in lower-income countries sometimes because of the limited level of financial sector development)13 but the percentage of people having problems in accessing or using credit products is still high.14 On the other hand, recent studies report the intense use by the poor of informal means to obtain credit or save.15 Family members and local money lenders, Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs),16 self-help groups, savings clubs and the ‘mattress’ represent for the poor valid alternatives to formal banking services, being flexible, negotiable and the creator of important social links.17 Nonetheless, most of these informal methods have the downside of being subject to the risk of fraud and collapse as well as of not allowing enough flexibility or charging too high interest rates or even employing aggressive collection practices (see money-lenders/sharks).18

Although data are difficult to evaluate, in the region of 2.5 billion people worldwide appear not to have access to formal financial services, most located in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Middle-East:19 56% of the world population does not benefit from any savings or credit product.20

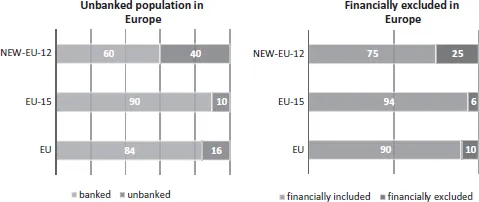

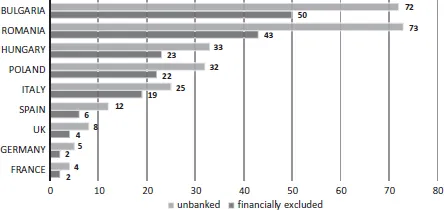

Even in the EU, in 2011, 16% of EU citizens were unbanked (without a bank account) while 10% were financially excluded (without a bank account or credit or savings product) but with relevant differences among Member States. In fact, the unbanked population in EU-15 was 10%, while it was 40% in EU-12 (i.e. new Member States since 2004) and the financially excluded was 6% in EU-15 and 25% in EU-12, with the highest figures in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Poland, followed, unexpectedly by Italy (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).21 In the same year, of the 56 million EU consumers not having a bank account, 6 million had their application rejected.22

Figure 1.1 Unbanked and financially excluded population in Europe in 2011 (%)

Figure 1.2 Unbanked and financially excluded population in Europe in 2011 (%)

Consequently, financial exclusion represents an important issue both in developing and ECA countries. However, while the credit crunch consequential to the financial crisis has made access to credit an urgent issue, traditional or new savings instruments (e.g. basic bank accounts) in Europe provided by postal services, public institutions and cooperative banks make the deposit side of the problem less pressing in the EU context (see Chapters 3, §5.a; 4, §6.b).

In Europe the attention is also focused on the access to funding by small and medium enterprises (SMEs). SMEs in fact represent 99% of the European non-financial enterprises (99.8% of EU-28 non-financial enterprises in 2014) and a good part of the aggregated production and jobs creation (78% of total employment and 71.4% of employment generation in 2014).23 Among SMEs, micro-enterprises (with less than ten employees and turnover below €2 million) correspond to 92% of European businesses but only to a small part of the sector income.24

A recent survey depicts the restricted access to financing as one of the most urgent problems for SMEs.25 SMEs mostly rely on bank financing since banks can partially overcome the asymmetric information related to the lack of verifiable public information about SMEs (and relative adverse selection and moral hazard problems) through the direct access to client-SMEs’ savings account information (see Chapter 6, §2.b–c).26 According to the same survey, about one third of SMEs applied for bank funding but obtained only a part ...