- 74 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In a multitude of ways, science affects the life of almost every person on earth. From medicine and nutrition to communication and transportation, the products of scientific research have changed human life. These changes have mostly taken place in the last two centuries, so rapidly that the average person is unable to keep informed. A consequence of this "information gap" has been the increasing suspicion of science and scientists. The lack of true understanding of science, especially of "fundamental" research, motivates this effort to narrow this gap by explaining scientific endeavor and the data-driven worldviews of scientists.

Key Features

- Fills an existing void in the understanding of science among the general population

-

- Is written in a nontechnical language to facilitate understanding

-

- Covers a wide range of science-related subjects:

-

- The value of "basic research"

-

- How scientists work by sharing results and ideas

-

- How science is funded by governments and private entities

-

- Addresses the possible dangers of research and how society deals with such risks

-

- Expresses the viewpoint of an author with extensive experience working in laboratories all over the world

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What is Science? by Jordanka Zlatanova in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

What Is Science?

Science is so important in our lives that we would expect it to be widely understood. But the word science means different things to different people. To some, it includes all of those endeavors that make practical use of our knowledge of the world—smartphones, penicillin, washing machines, etc. But development of such products or methods can perhaps better be called technology. Here the author concentrates instead on what is sometimes called basic or fundamental or pure science. This is a methodology for disciplined, critical study of the world around us and within us. It attempts to provide a rational, internally consistent view of that world and the dynamic processes that occur within it. It eschews supernatural explanations and rejects all those that are contradicted by solid evidence. Science is always skeptical. Basic science is not concerned with technology, although it frequently spawns technological advances. Its role in our lives is not well understood by many people.

It is also frequently looked upon with suspicion and doubt by nonscientists. The aim of the following chapters is to clarify what basic science and its relation to technology is, how it is done, who does it, and how scientists work. Hopefully, this can allow clearer discourse concerning the role of science in modern society. The first question to ask is how science, and the perceptions about it, came to be.

Rise of Science

Science, as defined earlier, is a relatively new worldview, nonexistent before the seventeenth century. In the preceding medieval world, scholarship was dominated by theology and the heavy significance given to those Greek philosophers, especially Aristotle, who had just been rediscovered. Their speculations on nature were not supported by experiment. There was widespread belief in magic and alchemy, especially as ways to gain power. A sole individual, the Italian Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), shines like a lighthouse at the end of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth century, the very end of medieval times. Leonardo was not only a master in art and engineering; his remarkable, precise drawings of plant and animal structures surpassed anything that would be done for hundreds of years. Some of Leonardo’s quotes, such as “Learning never exhausts the mind,” and “The noblest pleasure is the joy of understanding” show his inquisitive spirit. Yet, despite his objectivity and freedom from classical dogma, we probably should not call Leonardo the first scientist. He rarely proposed hypotheses or carried out controlled experiments. He did not share his work but carefully kept it secret, even to the extent of writing his notes in a secret code. One wonders what might have been if Leonardo had published his work.

Instead, science lay dormant for over a century. Then, in a brief, remarkable explosion in the 1600s, everything changed. The Italian Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) began to explore the universe with his telescope; his explorations earned him the name “father of modern physics” and “father of the scientific method.” Some of his well-known quotes include “All truths are easy to understand once they are discovered; the point is to discover them” and “I do not feel obliged to believe that the same God who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use.” “E pur si muove” (“And yet it moves”) is a phrase attributed to Galileo in 1633, after being forced by the Church to recant his claims that the Earth moves around the Sun, rather than the converse. This represents the spirit of a scientist who stays true to his convictions.

The English mathematician, physicist, and astronomer Isaac Newton (1643–1727) explained the universe dynamics using sophisticated new mathematics. His humbleness and his understanding of the enormity of science are reflected in his quotes: “If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants,” and “If I have done the public any service, it is due to my patient thought. To myself I am only a child playing on the beach, while vast oceans of truth lie undiscovered before me.”

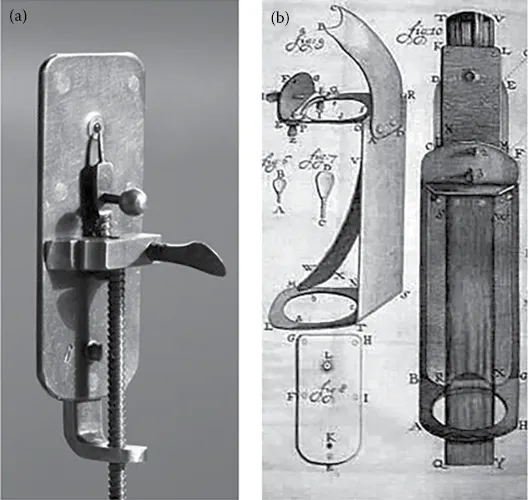

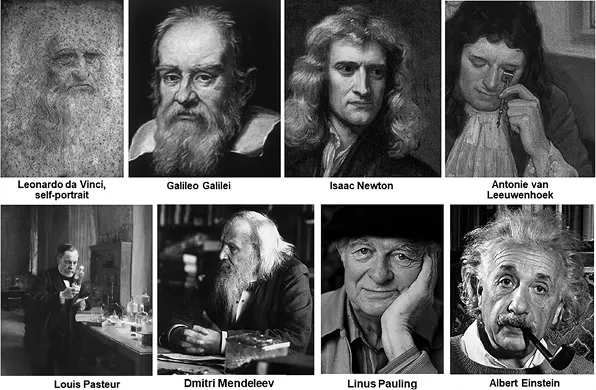

The Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), mainly self-taught, discovered the microbial world through the microscope he designed (Figure 1.1). He originally referred to the tiny creatures he observed as animalcules (from Latin animalculum, for “tiny animal”). These were primarily unicellular organisms, although he also observed multicellular organisms in pond water. He was also the first to document microscopic observations of bacteria, spermatozoa, red blood cells, muscle fibers, and blood flow in capillaries. His discoveries came to light through correspondence with the Royal Society, which published his letters. Pictures of these remarkable early scientists and those of a few equally remarkable scientists whose contribution to basic science is immense (Louis Pasteur, Dmitri Mendeleev, Linus Pauling, and Albert Einstein, see later in this chapter) are presented in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.1 Van Leeuwenhoek’s microscope. (a) Replica (from Wikipedia). (b) Schematic of the microscope as rendered by Henry Baker. Naturalist Leeuwenhoek’s single-lens microscopes used metal frames, holding hand-made lenses. They were relatively small devices, which were used by placing the lens very close in front of the eye. The other side of the microscope had a pin, where the sample was attached. There were also three screws to move the pin and the sample along three axes: one axis to change the focus and the other two to move the sample. (From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Van_Leeuwenhoek%27s/microscopes_by_Henry_Baker.webp.)

Figure 1.2 Great scientists whose contribution to our understanding of the laws of nature are immeasurable: Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Louis Pasteur, Dmitri Mendeleev, Linus Pauling, and Albert Einstein.

In the middle of that century (1668) was conducted what may have been the first true scientific experiment. The Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet Francesco Redi (1626–1697) was questioning the age-old doctrine of spont...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Chapter 1: What Is Science?

- Chapter 2: Scientists and What They Do

- Chapter 3: Is Science Dangerous?

- Chapter 4: How Is Dangerous Science Regulated?

- Chapter 5: Why Support Basic Research?

- Index