- 638 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Underwater Acoustic Modeling and Simulation

About this book

This newest edition adds new material to all chapters, especially in mathematical propagation models and special applications and inverse techniques. It has updated environmental-acoustic data in companion tables and core summary tables with the latest underwater acoustic propagation, noise, reverberation, and sonar performance models. Additionally

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

1.1 BACKGROUND

1.1.1 SETTING

Underwater acoustics entails the development and employment of acoustical methods to image underwater features, to communicate information via the oceanic waveguide, or to measure oceanic properties. In its most fundamental sense, modeling is a method for organizing knowledge accumulated through observation or deduced from underlying principles. Simulation refers to a method for implementing a model over time.

Historically, sonar technologists initiated the development of underwater acoustic modeling to improve sonar system design and evaluation efforts, principally in support of naval operations. Moreover, these models were used to train sonar operators, assess fleet requirements, predict sonar performance, and develop new tactics. Despite the restrictiveness of military security, an extensive body of relevant research accumulated in the open literature, and much of this literature addressed the development and refinement of numerical codes that modeled the ocean as an acoustic medium. This situation stimulated the formation of a new subdiscipline known as computational ocean acoustics. Representative developments in computational ocean acoustics have been documented by Merklinger (1987), Lee et al. (1990a,b,c, 1993), Lau et al. (1993), Murphy and Chin-Bing (2002), and Jensen (2008).

As these modeling technologies matured and migrated into the public domain, private industry was able to apply many aspects of this pioneering work. Subsequently, there has been much cross-fertilization between the geophysical-exploration and the sonar-technology fields as the operating frequencies of both fields began to converge. Recently, acoustical oceanographers have employed underwater-acoustic models as adjunct tools for inverse-sensing techniques (see Section 1.6) that can be used to obtain synoptic portraitures of large ocean areas or to monitor long-term variations in the ocean.

Underwater acoustic models are now routinely used to forecast acoustic conditions for planning at-sea experiments, designing optimized sonar systems, and predicting sonar performance at sea. Modeling has become the chief mechanism by which researchers and analysts can simulate sonar performance under laboratory conditions. Modeling provides an efficient means by which to parametrically investigate the performance of hypothetical sonar designs under varied environmental conditions as well as to estimate the performance of existing sonars in different ocean areas and seasons.

1.1.2 FRAMEWORK

A distinction is made between physical (or “physics-based”) models and mathematical models, both of which are addressed in this book. Physical models pertain to theoretical or conceptual representations of the physical processes occurring within the ocean; the term “analytical model” is sometimes used synonymously. Mathematical models include both empirical models (those based on observations) and numerical models (those based on mathematical representations of the governing physics). The subject of analog modeling, which is defined here as controlled acoustic experimentation in water tanks employing appropriate oceanic scaling factors, is not specifically addressed in this book. Barkhatov (1968) and Zornig (1979) have presented detailed reviews of acoustic analog modeling.

The physical models underlying the numerical models have been well known for some time. Nevertheless, the transition to operational computer models has been hampered by several factors: limitations in computer capabilities, inefficient mathematical methods, and inadequate oceanographic and acoustic data with which to initialize and evaluate models. Despite continuing advances in computational power, together with the development of more efficient mathematical methods and the dramatic growth in databases, the emergence of increasingly complex and sophisticated models continues to challenge available resources.

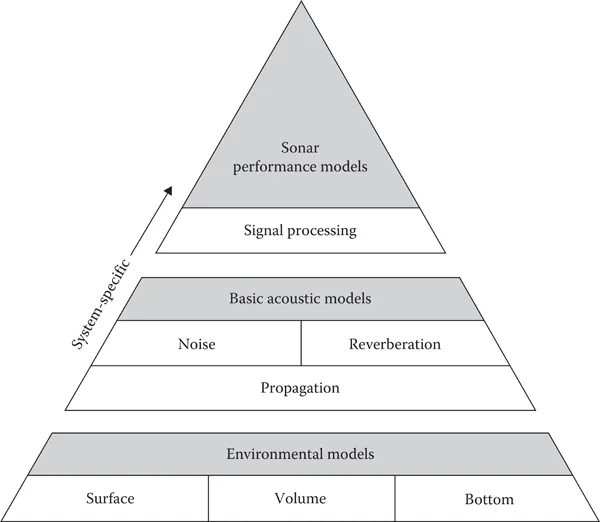

This book addresses three broad types of underwater acoustic models: environmental models, basic acoustic models, and sonar performance models.

The first category—environmental models—includes empirical algorithms that are used to quantify the boundary conditions (surface and bottom) and volumetric effects of the ocean environment. Such models include, for example, sound speed, absorption coefficients, surface and bottom reflection losses, and surface, bottom, and volume backscattering strengths.

The second category—basic acoustic models—comprises propagation (transmission loss), noise, and reverberation models. This category is the primary focus of attention in this book.

The third category—sonar performance models—is composed of environmental models, basic acoustic models, and appropriate signal-processing models. Sonar performance models are organized to solve specific sonar-applications problems such as submarine detection, mine hunting, torpedo homing, and bathymetric sounding.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the relationships among these three broad categories of models. As the applications become more and more system specific (i.e., as one progresses from environmental models toward sonar performance models), the respective models become less universal in application. This is a consequence of the fact that system-specific characteristics embedded in the higher-level models (for example, signal-processing models) restrict their utility to particular sonar systems. Thus, while one propagation model may enjoy a wide variety of applications, any particular sonar performance model is, by design, limited to a relatively small class of well-defined sonar problems.

At the base of the pyramid in Figure 1.1 are the environmental models. These are largely empirical algorithms that describe the boundaries of the ocean (surface and bottom) and the water column. The surface description quantifies the state of the sea surface including wind speed, wave height, and bubble content of the near-surface waters. If ice covered, descriptions of the ice thickness and roughness would also be required. Surface-reflection coefficients and surface-scattering strengths are needed to model propagation and reverberation. The bottom description includes the composition, roughness, and sediment-layering structure of importance to acoustic interactions at the sea floor. Bottom-reflection coefficients and bottom-scattering strengths are needed to model propagation and reverberation. The volume description entails the distribution of temperature, salinity and sound speed, absorption, and relevant biological activity. Volume scattering strengths are needed to model reverberation. Once the marine environment is adequately described in terms of location, time and frequency (spatial, temporal and spectral dependencies), the basic acoustic models can be initialized. In order to proceed higher up in the pyramid, it is first necessary to generate estimates of acoustic propagation. If a passive sonar system is being modeled, it is necessary to understand the propagation of sound as it is radiated from the target toward the sonar receiver. Furthermore, any interfering noises must be propagated from their source to the sonar receiver. The behavior of the noise sources can be quantified using noise models, which must include a propagation component. If an active sonar system is being modeled, the contribution of reverberation must be considered in addition to those factors already mentioned above with regard to noise sources. Moreover, since the active sonar transmits a signal, sound must be propagated out to the target and back. Also, the transmitted pulse will be scattered and returned by particulate matter in the ocean volume. Reverberation models quantify the effects of scatterers on the incident pulse and its subsequent scattering and propagation back to the sonar receiver and, therefore, must include a propagation component. Finally, the outputs of the environmental models and basic acoustic models must be combined with sonar performance models, in conjunction with appropriate passive or active sonar signal processing models. In concert, these models generate metrics useful in predicting and assessing the performance of passive or active sonars in different ocean environments and seasons. The inclusion of sonar system and target parameters is not explicitly discussed at this level but will be treated in Section 11.4.2.

The wide breadth of material covered in this book precludes exhaustive discussions of all existing underwater acoustic models. Accordingly, only selected models considered to be representative of each of the three broad categories will be explored in more detail. However, comprehensive summary tables identify all known basic acoustic models and sonar performance models. These tables also contain brief technical descriptions of each model together with pertinent references to the literature. Notable environmental models are identified and discussed in appropriate sections throughout this book.

Modeling applications will generally fall into one of two basic areas: research or operational. Research-oriented applications are conducted in laboratory environments where accuracy is important and computer time is not a critical factor. Examples of research applications include sonar-system design and field-experiment planning. Operationally oriented applications are conducted as field activities, including fleet operations at sea and sonar-system training ashore. Operational applications generally require rapid execution, often under demanding conditions; moreover, modeling accuracy may be subordinate to processing speed.

1.2 MEASUREMENTS AND PREDICTION

The scientific discipline of underwater acoustics has been undergoing a long transition from an observation phase to a phase of understanding and prediction. This transition has not always been smooth: direct observations have traditionally been limited, the resulting prediction tools (models) were not always perfected, and much refinement remains to be completed.

Experimental measurements in the physical sciences are generally expensive due to instrumentation and facility-operation costs. In the case of oceanographic and underwater acoustic data collection, this is particularly true because of the high costs of platform operation (ships, aircraft, submarines, and satellites). Acoustic datasets obtained at sea are limited by their inherent spatial, temporal and spectral dimensions. Consequently, in the field of underwater acoustics, much use is made of what field measurements already exist. Notable large-scale field programs that have been conducted successfully in the past include AMOS (Acoustic, Meteorological, and Oceanographic Survey) and LRAPP (Long Range Acoustic Propagation Project). More recent examples include ATOC (Acoustic Thermometry of Ocean Climate) and other basin-scale tomographic experiments.

The National Science Foundation’s ocean observatories initiative (OOI) is a new program designed to implement global, regional and coastal-scale observatory networks (along with cyberinfrastructure) as research tools to provide long-term and real-time access to the ocean. Three acoustic-measurement technologies were proposed for incorporation (Duda et al., 2007): long-range positioning and navigation, thermometry, and passive listening. Passive-listening techniques can be used for marine-mammal and fishery studies, for monitoring seismic activity, for quantifying wind and rain, and for monitoring anthropogenic noise sources.

According to the Office of Naval Research (US Department of the Navy, 2007), ocean acoustics is considered to be a US national naval responsibility in science and technology. The three prime areas of interest are shallow-water acoustics, high-frequency acoustics, and deep-water acoustics.

- Shallow-water acoustics is concerned with the propagation and scattering of low-frequency (10 Hz to ~3 kHz) acoustic energy in shallow-water ocean environments. Specific components of interest include: scattering mechanisms related to reverberation and clutter; seabed acoustic measurements supporting geoacoustic inversion; acoustic propagation through internal waves and coastal ocean processes; and the development of unified ocean-seabed–acoustic models.

- High-frequency acoustics is concerned with the interaction of high-frequency (~3 kHz to 1000 kHz) sound with the ocean environment, with a view toward mitigation or exploitation of the interactions in acoustic detection, classification, and communication systems. Specific components of interest include: propagation of sound through an intervening turbulent or stochastic medium; scattering from rough surfaces, biologics, and bubbles; and penetration and propagation within the porous seafloor.

- Deep-water acoustics is concerned with low-frequency acoustic propagation, scattering and communication over distances from tens to thousands of kilometers in the deep ocean where the sound channel may, or may not, be bottom limited. Specific components of interest include effects of environmental variability induced by oceanic internal waves, internal tides, and mesoscale processes; effects of bathymetric features such as seamounts and ridges on the stability, statistics, spatial distribution, and predictability of broadband acoustic signals; and the coherence and depth dependence of deep-water ambient noise.

Modeling has been used extensively to advance scientific understanding without expending scarce resources on additional field observations. The balance between observations and modeling, however, is very delicate. Experimenters agree that modeling may help to build intuition or refine calculations, but they argue further that only field observations give rise to genuine discovery. Accordingly, many researchers find mathematical models most useful once the available observations have been analyzed on the basis of simple physical models.

The relationship between experimentation and modeling (in the furtherance of understanding and prediction) is depicted schematically in Figure 1.2. Here, physical models form the basis for numerical models while experimental observatio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Preface to the Fourth Edition

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Author

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Acoustical Oceanography

- Chapter 3 Propagation I: Observations and Physical Models

- Chapter 4 Propagation II: Mathematical Models

- Chapter 5 Propagation II: Mathematical Models

- Chapter 6 Special Applications and Inverse Techniques

- Chapter 7 Noise I: Observations and Physical Models

- Chapter 8 Noise II: Mathematical Models

- Chapter 9 Reverberation I: Observations and Physical Models

- Chapter 10 Reverberation II: Mathematical Models

- Chapter 11 Sonar Performance Models

- Chapter 12 Model Evaluation

- Chapter 13 Simulation

- References

- Appendix A: Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Appendix B: Glossary of Terms

- Appendix C: Websites

- Appendix D: Problem Sets

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Underwater Acoustic Modeling and Simulation by Paul C. Etter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.