![]()

Perceptions of Library Leadership in a Time of Change

Peter V. Deekle

Ann de Klerk

What does the future hold for academic libraries? Are they poised at the brink of an enhanced and integrated role in higher education, or will they suffer the fate of medieval scribes?

A 1991 survey of the chief academic officers and library directors at over 250 small and medium-sized private colleges and universities conducted by the authors of this article showed that there were differences in the perceptions of library futures both among library directors and between them and chief academic officers. While traditional roles were reinforced by many survey respondents, significant innovative expectations of libraries were expressed by several directors and academic leaders. Most respondents acknowledged that changes in library administrative roles are at hand, and a few were prepared to meet the resulting new leadership challenges. It was clear from the survey returns, however, that most directors were awaiting initiatives from their peers before taking action themselves. The survey provided some insight into current perceptions and the authors suggest that the convergence of academic officer and library director perceptions is a starting point for forging a new vision of academic libraries.

The modern academic library has had a tradition of addressing information service concerns independently within the parent institution. Recently, there have been some radical associations with, initially, curriculum development (the Library college, bibliographic instruction, and currently, information literacy) and, more recently, information management (computer-based applications and associated technology, telecommunications, and networking). The influence of these new associations appears to be changing the role of academic libraries and academic library directors, and calls for a closer working relationship with more campus administrative and academic constituencies. Gordon Gee and Patricia Breivik have defined this relationship in the following statement: “Libraries do have a unique role to play in the search for academic excellence–the trouble is, most academic administrators do not know this. They do not plan for or even think about an active educational role for academic librarians.”1 A report in Research Libraries Group News further defines this relationship: “Libraries have been able to make a good deal of progress in partnerships with other libraries, but future projects will depend on new kinds of partnerships being forged with provosts, with faculty, with scholarly associations, with campus information czars … the shape of the future will depend on these new alliances.”2

Peter V. Deekle is University Librarian and Director, Blough-Weis Library, Susquehanna University, Selingsgrove, PA. Ann de Klerk is Director of the Library and Instructional Media Services, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA.

Significant emerging trends in higher education which have major implications for academic libraries include: (1) advances in telecommunications and computer technology, (2) changes in curricula which recognize the interrelationship of academic disciplines, (3) increases in user demand for prompt and responsive information service, (4) a frustrating sense of information overload for both faculty and student clienteles, (5) a corresponding need for greater user discretion and selectivity amid the glut of information, (6) funding and spatial constraints which limit acquisitions, storage, and service options, (7) a need for effective administrative responsiveness toward fundraising and consortial requirements, and (8) the management issues associated with changing organizational structures and staffing in response to changing needs of users.

The authors of this article stated in the cover letter of their survey addressed to library directors and chief academic officers, June 1991, “We believe that the complexity, rapidity and magnitude of the information revolution has contributed to a multiplicity of perceptions about the role of academic libraries in the current teach ing/learning process and in higher education in general.” The authors wanted to identify what library directors (from now on referred to as “directors”) and chief academic officers (henceforth designated “administrators”) perceived as the current and future role of libraries and their directors, and the nature of perceptual differences of these two groups.

TOPICS OF CONCERN

This report of survey findings reaches some preliminary conclusions. In a future report, the authors will propose courses of action to help close the perceptual gap revealed by the survey.

Discussions with colleagues in various academic and administrative settings have centered around many of the following topics: (1) Have the responsibilities of librarians really changed? What is the role of library support staff and how does the present library staffing model effectively integrate diverse staff categories? What might be the optimal organizational model? (2) Given the convergence of information and computing technologies, how might the library and computer center most effectively interact and in what organizational structure? (3) To whom does the library report and where should it report? Does the library have a prominent and proactive role in institutional governance structures and in strategic planning institution-wide? (4) What role does or should the library play in curriculum planning and development of information literacy? (5) What role does or should the library play in strengthening the funding base for library and information services? There has been much speculation from many disciplines on the possible effects of the information revolution on libraries and information management, but as yet no clear new paradigm has emerged.

THE SURVEY

The authors decided to seek answers from directors and administrators, since, in common with others, the authors sensed an increased importance of mutual understandings between directors and administrators. Not intending to survey a random sample, an entire population, derived from the Carnegie institutional classifications, was selected. A survey instrument was used to solicit perceptions and ideas on current and perceived trends from the two designated Carnegie institutional groups.

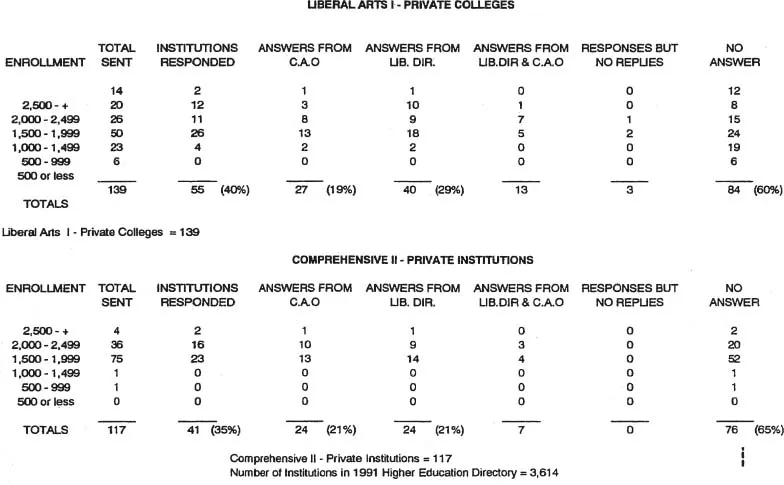

The study of attitudes was based on individual and subjective comments to survey questions; it was not intended to be a statistically controlled study. An initial decision was to send separate but identical questionnaires to be independently completed and returned by directors and administrators from the two clearly defined groups of private colleges and universities, groups in which the authors of the study are currently employed. The survey population included 139 institutions in the Liberal Arts Colleges-Private Colleges I (Survey Group I) and 117 Comprehensive Private Institutions II (Survey Group II). Forty percent of Group I institutions responded, and 35% of Group II. Most responses came from institutions with enrollments of 1,500 to 2,500 students (FTE); half the number of Group I institutions responding to the survey had student enrollments of 1,000 to 1,500 FTE (see Figure 1).

The survey instrument was organized in the five topical sections described above. The authors did not discern major differences among the responses of the two survey groups, directors and administrators of Liberal Arts Colleges I and Comprehensive Universities II. Quotations and references were taken directly from the survey responses without attribution to illustrate, from the authors’ viewpoint, a particularly significant perspective on an issue; only the respondent category (chief academic officer or library director) was identified.

Role and Responsibilities of the Library

The first section of survey questions attempted to determine what directors and administrators perceived as the responsibilities of library staff and how libraries were and should be organized to effectively meet those responsibilities. A few respondents saw librarians in a very traditional way: “The primary responsibilities of librarians are to select, make secure, preserve, and provide access to information sources that are needed by those who use academic libraries.” One director wrote, “If librarians are to shed traditional organizational and archival tasks, they are obviously not going to be librarians any more. Why don’t we retire the title?” An administrator viewed responsibilities as including: “Organization and direction of the library staff and all policies and procedures regarding budgeting, acquisition, and distribution of library resources.”

FIGURE 1

OVERVIEW OF RESPONSES FROM SURVEYED INSTITUTIONS

Most directors and administrators saw the library as having somewhat extended their traditional role quantitatively while not having changed it qualitatively. In the words of one director, “Emerging technologies have already changed some of the operational ways in which we support the curriculum but those changes do not at this time appear to represent a qualitative transformation of a professional mission. Although we are doing it differently, we are still doing the same fundamental things.” Another said, “Librarians will continue to serve as the intermediary between information and the user. While how we do it may change, this remains our primary function.” An administrator agreed: “The forms of access and the media for information have changed but not the function.”

In what ways, precisely, have the library’s activities changed? Many respondents acknowledged that libraries still perform the same functions. The survey sought to clarify the nature of libraries’ primary responsibilities.

The large majority of both directors and administrators spoke of the importance of educating users: not only collecting or providing access to information sources but also educating library users. Both directors and administrators saw the education function as a high priority. Neither, however, have the successful ways of addressing this priority been specified, nor have libraries advanced as proactive agencies in response to new needs and current pedagogy.

A broader role for libraries and librarians is envisioned by a few respondents. One administrator defined the library’s role as “responsive to (even anticipate, if possible) important changes in the delivery of library services; to engage in strategic planning around collections so as to make the best possible use of available resources.” Another cited a library’s “anticipation and preparation for future need.” Still another administrator said that the library’s job was to plan “for information services in concert with other administrators.”

A director remarked, “Librarians will need to interact with many other campus agencies to a far greater extent then previously.” An administrator declared: “It appears the trend will be a concept of the library not as a place, but as a service that can be accessed from many areas. This is a change in philosophy and habit patterns for many.”3

Discussion

The responses to the survey questions concerning perceived library roles and missions and staffing distinctions indicated a prevailing preference for proactivity. Yet neither directors nor administrators articulated a strategy to ensure or enhance the proactive library. Respondents recognized as appropriate the library’s recognized responsibility for increasing information access. The majority desired a larger leadership role for libraries. Only a few responses favored the status quo.

Staffing

The role and position of “highly skilled and educated professionals who are not librarians (often called paraprofessionals) has continued to be an unresolved issue.” Several themes regarding this issue have emerged from the comments of directors and administrators. “Certainly, in academe this issue has not been confined to libraries.” “… It applies across campus as new and rapidly changing technologies continually increase required entry level skills.” Several library directors agreed with Larry Hardesty, that “as librarians assume increased administrative, information management and teaching responsibilities, they do indeed shed many of their traditional organizational and archival tasks.”4 They will need to delegate many tasks to others who are skilled and educated.

It was clear that both respondent groups differentiated between librarians and their supporting staff, and other related non-library personnel. There are those positions which have traditionally been called paraprofessionals, that is, support staff with or without bachelor’s degrees who have taken on higher level tasks once done by librarians (e.g., many cataloging activities, interlibrary loan, information desk service). There are also an increasing number of personnel who are not librarians but who are professionals in their own right (e.g., systems managers, acquisitions and budget managers with accounting degrees, archivists).

Recognizing the increasing diversity and strengths of library personnel, both library directors and university administrators spoke to the need for staff development support and articulated career paths for those who are professionals but not librarians. Salaries for this group should be reviewed and adjusted to reflect the heightened complexity of job responsibilities. These “non-librarian” staff groups were cited as an integral part of the library team. While librarians should continue to make policy decisions, it was suggested that this group could provide first line supervision and should have input into recommendations. One administrator wrote, “The creation of an exclusionary [sic] caste system based on degree ownership rather than on accomplishment, productivity and competence can be quite harmful.”

In regard to librarians, a respondent stated, “The MLS remains the most important single credential for the entry level librarian, but it may not be the only credential for all positions. Increasingly the library staff composed of professionals and paraprofessionals whose education and experience are markedly different from traditional library science backgrounds.”

Discussion

As a minimal degree of recognition, it seems to the authors that a term other than paraprofessional must be adopted or devised to recognize important members of the team who now deliver library services. The term should describe what they do in a primary, not subordinate, fashion. The authors note that this issue has long been discussed within the profession and no resolution has been achieved.

The growing complexity and diversity of library staffing was widely recognized by both administrators and directors. The survey returns emphasized the coordination of library staffing activities and responsibilities in a team approach. The authors have associated this coordination of staffing with the library profession’s characteristic ability to build partnerships with internal and external agencies and individuals.

Organizational Structure and Inclusion in Governance

The administrative organizational model (in place or preferred) was the overwhelming preference and current prevaili...