![]()

1 Introduction

Melanie Franklyn and Peter Vee Sin Lee

Impact injury biomechanics involves the study of human tolerance to impact loading. Using the principles of mechanics, the discipline focuses on the mechanisms of injury in traumatic events such as military scenarios and automotive impacts. When a traumatic event occurs, the impact loading causes deformation of the tissues beyond their failure limits, resulting in anatomical lesions or altered physiological function. Injury prediction and prevention involves using tools and techniques to determine the specific causes of the trauma and the effect of variables such as the injury mechanism, impact surface, rate of impact and the material properties of the tissue in order to reduce the likelihood of injury and design better countermeasures to minimise trauma to the individual.

Injuries resulting from high-speed impact became an emerging problem with the introduction of motorised vehicles in the late 1880s, and as automobiles became more widespread, predominately in the early 1900s, the number of crashes started rising. This led to a dramatic increase in the prevalence of injuries and fatalities sustained in these events, particularly as these ‘horseless carriages’ had no safety features in addition to a multitude of other issues such as hard interiors and a non-compliant steering wheel. Ironically, although the safety belt was used in horse-drawn carriages as early as the 1850s, they would not be standard issue in motor vehicles until the early 1960s. In the 1920s, one of the early pioneers in crash investigation was Hugh De Haven. Having survived an aeroplane crash when he was serving as a combat pilot cadet in the Canadian Royal Flying Corps during WWI, De Haven commenced his investigations into injuries sustained in traumatic events such as aeroplane crashes and falls; in the latter case, he was particularly interested in individuals who had fallen from a great height and survived (Hurley et al. 2002). De Haven later established the Crash Injury Research project at Cornell in the 1940s for investigating motor vehicle crashes.

With the advent of WWII, there were significant developments in the field, predominately in the specialities of brain injuries and aviation medicine. Australian-born neurosurgeon Hugh W.B. Cairns, who was both an advisor on head injuries for the UK Ministry of Health and a consultant neurosurgeon to the British Army, became an influential advocate for the use of helmets by motorbike riders for preventing brain injuries, particularly after his experience as one of the attending physicians for Colonel T.E. Lawrence after the latter’s fatal motorbike crash in 1935 (Lanska 2016; Marriott and Argent 1996). About the same time, two British neurologists, Majors D. Denny-Brown and W.R. Russell, both of the Royal Army Medical Corp and the University of Oxford, developed an animal model for brain injury, demonstrating that suddenly applied acceleration could result in concussion (Lanska 2016).

The results of this earlier work led A.H.S. Holbourn, a research physicist at the Department of Surgery, the University of Oxford, to postulate on the cause of brain injuries in 1943, stating that angular acceleration without impact was an important head injury mechanism. From 1939, Lissner and Gurdjian were also studying head trauma but at Wayne State University. Using cadaveric heads, they developed their theory of linear acceleration as a cause of brain injury, which later led to the Wayne State Tolerance Curve (Lanska 2016).

Whilst these important developments in brain injury research were transpiring, advances in aviation medicine were emerging when it became critical to address the problem of trauma in jet aircraft and aeroplane crashes. Both the UK and Germany recognised there was a need to understand the tolerance of the spine to injury and conducted some of the early experiments in the field. Much of this data was not published until after the war, in particular, a large body of German aviation medicine research. The Americans realised the importance of this work and facilitated the publication of this data from German to English, thus making the spinal injury work and injury tolerance curves developed by researchers such as Ruff and Geertz accessible (German Aviation Medicine in World War II 1950).

In the late 1940s, the US military surgeon Colonel John Paul Stapp studied the effects of deceleration on the human body using a rocket sled, using himself as a test subject. Stapp was interested in applying the results to aircraft crashes in addition to studying the effect of seats and harnesses in a crash. This research continued through several organisations in the 1950s and 1960s and led to the development of a number of injury curves and injury models which are still in use today. This work includes that of Eiband of NASA, US (Eiband 1959), which led to the well-known Eiband curve for rapidly applied acceleration, and Ruff of Germany (Ruff 1950), who established an injury curve for whole-body tolerance under acceleration. In the latter part of the 1950s, Latham of the Royal Air Force Institute of Aviation Medicine, UK, introduced the mechanical spring-mass model for vertical loading to examine spinal injuries for pilots in ejection seat scenarios; the concept of which was later developed by Stech and Payne (1969) and Brinkley and Shaffer (1971) to become the Dynamic Response Index (DRI) model.

In order to further assess the effect of pilot ejection seats, pilot restraint harnesses and restraint systems for military vehicles, Sierra Sam, a 95th percentile male anthropomorphic test device (ATD), was created by Alderson Research Laboratories and Sierra Engineering for the military in 1949. This was later followed by other ATDs such as the VIP (Very Important Person) series in 1966, which was developed for Ford and General Motors and specifically designed for automotive safety. However, the automotive industry was becoming more concerned about reducing motor vehicle trauma. In the late 1960s, Stapp changed the focus of his experiments from military to automotive safety research through the initiative of the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), and in the early 1970s, General Motors commenced their own testing and research programme, developing the hybrid series of ATDs which are still in use today.

While there has been extensive research into automotive crashes and vehicle occupant safety over the last 50 years, this has not been the case for impact injuries sustained in military events. This has been due to, in part, the changing threats combatants have been exposed to. Since the 1970s, military injury research has predominately focused on issues like blast-related trauma and overuse injuries such as stress fractures, with only more recent work including the analysis of injury mechanisms of blunt trauma sustained by soldiers in military vehicles subjected to improvised explosive device (IED) events. Consequently, many of the standards currently used to assess military impact injuries were developed in the 1950s–1970s, while studies published at the time often presented limited data or omitted critical information, such as loading rates. Thus, injury criteria developed for ATDs used to assess impact injury potential in military vehicle tests are heavily based on pilot ejection studies or automotive data–situations they were not designed for. For example, the DRI originated from pilot ejection studies, while other measures such as the Head Injury Criterion (HIC) and the Viscous Criterion (VC) were developed for automotive impacts.

In addition to the limitations of injury criteria for assessing military impact injuries, the ATDs used to measure them were not designed for underbelly blast testing. Both the automotive Hybrid III and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Hybrid III are currently used for live-fire testing and evaluation of military vehicles; however, the automotive Hybrid III is a regulatory frontal-impact crash test ATD, while the FAA Hybrid III was designed for assessing spinal injury potential in light aeroplane crashes. Nevertheless, to date, there have been no alternative forms of assessment, and these mannequins remain the only alternative for underbelly live-fire testing injury evaluation.

Due to the significant limitations in the current ATDs and injury criteria for assessing the type of injuries sustained in underbelly blast events, there have been, more recently, significant research efforts towards developing new ATD components and a new military ATD. For example, the Mil-Lx (Military Lower Extremity) leg, which is a straight leg optimised to measure vertical loading, was developed through a collaboration between Humanetics (Denton ATD) and Wayne State University and is currently used in live-fire testing and evaluation. More recently, the WIAMan (Warrior Injury Assessment Manikin) initiative to develop an ATD specifically for underbelly blast testing has resulted in ongoing research and development to investigate the causes and mechanisms of the different types of injuries sustained in these events. In addition, there are a number of large research programmes to determine the effect of different variables such as loading rates and peak acceleration levels under vertical loading. Recent studies on the sizes of current military vehicle occupants are also being performed, as the anthropometry of the currently used ATDs are not representative of today’s military combatant.

Other emerging research on military impact injuries includes computational modelling efforts such as finite element analysis, where parametric studies on different loading conditions are leading to a better understanding of the injury mechanisms involved in underbelly blast events. In the ballistics and behind armour blunt trauma (BABT) field, the rapid development of new materials has led to significant improvements in the design of helmets and body armour; however, the techniques used to assess them, which were developed in the 1960s, have very little correlation with brain or thorax injuries. Consequently, recent research in this area has focused on gaining a better understanding of the relationship between backface deformation and injury outcome and potentially establishing new standards for assessment.

Clearly, a substantial amount of historical military and automotive impact data is still in use today; however to date, this information has not been presented and discussed in any single publication. Thus, it is hoped that this book will be an invaluable learning and reference guide, both for researchers already working in the field of military injury biomechanics and individuals new to the discipline. While the chapters cover the historical background and development in the different areas of impact injury, current research is also discussed. Although the discipline is rapidly evolving, this book should provide researchers with an invaluable contemporary source of information which can be used as a study or reference guide.

REFERENCES

Brinkley, J.W. and Schaffer, J.T. 1971. Dynamic Simulation Techniques for the Design of Escape Systems: Current Applications and Future Air Force Requirements. AMRL-TR-71-291971. Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH.

Eiband, A.M. 1959. Human Tolerance to Rapidly Applied Accelerations: A Summary of the Literature. NASA-MEMO-5-19-59E. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Cleveland OH.

German Aviation Medicine in World War II. 1950. Volumes I and II. Department of the Air Force, US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Hurley, T.R., Vandenburg, J.M. and Labun, L.C. 2002. Introduction to Crashworthiness. In: Hurley, T.R. and Vandenburg, J.M. Eds. Small Airplane Crashworthiness Design Guide. Simula Technologies, TR-98099. Phoenix, AZ, pp. 1–9.

Lanska, D.J. 2016. Traumatic Brain Injury Studies in Britain during World War II. In: Tatu, L. and Bogousslavsley, J. War Neurology. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. Karger, Basel, Switzerland, pp. 68–76.

Marriott, P. and Argent, Y. 1996. The Long Wait, 14–19 May 1935. In: The Last Days of T.E. Lawrence, Chapter 13, The Alpha Press, Brighton, Great Britain.

Ruff, S. 1950. Brief Acceleration: Less than One Second. In: German Aviation Medicine, World War II, Volume I. Department of the Air Force, pp. 584–598.

Stech, E.L. and Payne. P.R. 1969. Dynamic Models of the Human Body. AMRL-TR-66-157. Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH.

![]()

2 Ballistic Threats and Body Armour Design

Johno Breeze, Eluned A. Lewis, and Debra J. Carr

CONTENTS

2.1 Types of Ballistic Threats on the Modern Battlefield

2.1.1 Introduction

2.1.2 Energised Fragments

2.1.3 Ammunition

2.1.4 Shotguns and Less Lethal Kinetic Energy Devices

2.1.5 Summary

2.2 Projectile–Tissue Interaction

2.2.1 Introduction

2.2.2 Permanent Wound Tract

2.2.3 Damage Produced Specifically by the Temporary Cavity

2.3 Personal Protective Equipment for Military Personnel

2.3.1 Introduction

2.3.2 Military Body Armour and Helmets

2.3.3 Essential and Desirable Medical Coverage

References

2.1 TYPES OF BALLISTIC THREATS ON THE MODERN BATTLEFIELD

2.1.1 INTRODUCTION

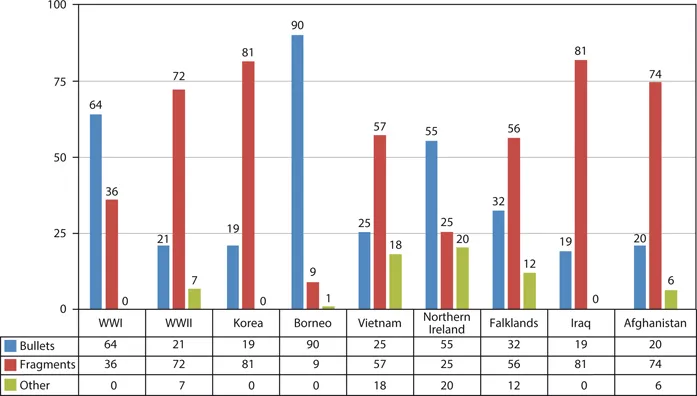

The modern battlefield contains a wide variety of ballistic threats that military personnel may encounter, and these threats may change depending on the conflict and as a conflict matures. Intelligence as to the nature of the threat is essential for optimising protection. Ballistic threats not only come from enemy combatants but also include those utilised by the civilian populace as well as allies or own forces. The key to optimising protection lies with an ability to rapidly scale any personal armour worn both for its ballistic protective ability as well as the anatomical coverage provided based upon the threat. Since World War I (from a UK perspective), fragmentation wounds have generally outnumbered those caused by bullets, with the exception of particular smaller scale conflicts such as those involving jungle warfare (e.g. Borneo) and internal security operations (e.g. Northern Ireland) (Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1 Incidence of battle injury (%) by wounding type (other injury causes include interpersonal assault and blunt trauma). (From Carey, M.E., Journal of Trauma, 40, S165–S169,...