- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book examines the contexts into which Puerto Rican immigrants to the United States stepped, and the results of their interaction within those contexts. It focuses mainly on New York City, essentially a social history of the post-World War II Puerto Rican community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Puerto Ricans by Clara E Rodriguez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

International Relations1

The Colonial Relationship: Migration and History

Since 1898, all Puerto Ricans have been born in the U.S.A., for that was the year that the United States invaded Puerto Rico as part of its war with Spain and proceeded to make Puerto Rico an unincorporated territory of the United States. All Puerto Ricans born in Puerto Rico since that time have been born on U.S. soil. This book, however, focuses on Puerto Ricans who were born and/or live in the fifty states. For these Puerto Ricans, being "born in the U.S.A." has had quite a different meaning. This book will explore this meaning.

Looked at in historical perspective, Puerto Rican migration and immigration have always been greatly influenced by economic developments in Puerto Rico. In turn, these developments have been influenced by the political and economic ties that have existed between Puerto Rico and its colonial power, first Spain and then the United States.1 This chapter will address these relationships, as well as the migration itself: who came, why they came, and where they settled. The second part of this chapter analyzes the impacts of Puerto Rico's colonial history on the post-World War II Puerto Rican communities in the United States.

The Migration

Despite the tendency in the literature to view the Puerto Rican migration as homogeneous, in real terms, the migration was quite diverse. It included many from the campos, the rural areas, where the farming pursuits of many were rendered economically marginal; these migrants were, essentially, displaced farmers and farm laborers. They migrated directly to New York City, to other large cities, or to small towns and farming communities, where they first worked as agricultural laborers and then moved to more urban areas. Others came from the pueblos (towns) in Puerto Rico. For many of these the trek to the states was a second migration. They were often only a generation or less removed from campo living and were under- or unemployed in the small towns or large urban areas to which they had migrated in Puerto Rico. They followed the same paths as those from the campos. After 1965, those who arrived were generally already highly urbanized; they had, in many cases, already become urban proletarians and were familiar with the ways of urban living. (Today the agricultural sector is so minor in Puerto Rico, and the urban-suburban residential patterns so pronounced, that the distinction between rural and urban that formed the basis of much earlier research has lost much meaning.)

Lost in most analyses of immigrants is a real qualitative sense of the diversity and richness of the migrant population. Often the data used in academic studies identify certain patterns of class and skill background, but, because they are based on standardized classifications of jobs developed for use in the United States, they misclassify or fail to identify the varied skills and talents of those who migrate from different cultures. For example, in the migration of Puerto Rican peasants and urban workers alike, there were sugar cane cutters and common laborers, but there were also accomplished musicians, fine needlecraft workers, country doctors and midwives, small entrepreneurs, botanists, spiritualists, practical agronomists, skilled artisans (in wood, cement, and leather), artists, singers, and able political workers long involved in the legal and political systems of Puerto Rico. The skills these migrants brought with them were seldom utilized for their livelihood; in many cases, these skills went entirely unnoticed in the new land.

Just as the migrants brought nontransferable skills, they also brought transferable skills that were not transferred. As Handlin (1959: 70) points out, as newcomers "they had to accept whatever jobs were available. Even those who arrived with skills or had training in white collar occupations had to take whatever places were offered to them." Many who had been schoolteachers in Puerto Rico migrated and became factory workers, cab drivers, and restaurant workers. Thus, although some statistical measures may reflect a fairly uniform class structure, the measures do not adequately account for nontransferable skills and the downward mobility initially experienced by many migrants. The Puerto Rican population is a heterogeneous one that reflects the distinct classes found on the island plus the development of new class positions and perspectives in the United States.

Patterns of Settlement

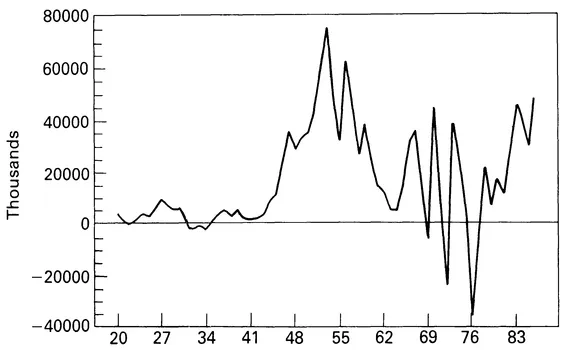

There have been Puerto Ricans, and even Puerto Rican organizations, in New York since the nineteenth century (Iglesias, 1980; Sánchez-Korrol, 1983). However, it was only after 1900 that significant numbers of Puerto Ricans came, with the bulk of the migration occurring in the 1950s and 1960s (see Figure 1.1). The migration of Puerto Ricans after the U.S. takeover has been classified into three major periods (Stevens-Arroyo and Díaz-Ramírez, 1982). During the first period, 1900-1945, the pioneers arrived. The majority of these pioneros settled in New York City, in the Atlantic St. area of Brooklyn, El Barrio in East Harlem, and other sections of Manhattan (e.g., the Lower East Side, the Upper West Side, Chelsea, and the Lincoln Center area), while some began to populate sections of the South Bronx. During this period, contracted industrial and agricultural labor also arrived and "provided the base from which sprang many of the Puerto Rican communities" outside of New York City (Maldonado, 1979: 103).

The second phase of migration, 1946-1964, is known as "the great migration" because the largest numbers of Puerto Ricans arrived. During this period the already established Puerto Rican communities of East Harlem, the South Bronx, and the Lower East Side increased their numbers and expanded their borders. Settlements in new areas of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Chicago, and other areas of the country appeared and grew, but the bulk of the Puerto Rican population continued to reside in New York.

Figure 1.1 Migration from Puerto Rico, 1920-1986

Sources: For data from 1920 to 1940: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1976). For data from 1940 to 1986: Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, Negociado de Análisis Económico, 1940-1986.

Sources: For data from 1920 to 1940: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1976). For data from 1940 to 1986: Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, Negociado de Análisis Económico, 1940-1986.

The last period is termed "the revolving-door migration." It is dated 1965 to the present and involves a fluctuating pattern of net migration as well as greater dispersion to other parts of the United States. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, the last few years have shown net outflows from Puerto Rico that begin to rival those experienced in the early 1950s. By 1980, the majority of Puerto Ricans in the United States were living outside of New York State (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1982:6).

Contract Laborers

Contract laborers have been another stream in the Puerto Rican migration, but they have generally received little attention in the literature. This may be because many returned to Puerto Rico after their contracts were completed, while others moved quickly out of agricultural contract labor and settled in more urban areas. Initially recruited by companies and then by the "family intelligence service," these migrants formed the nucleus of Puerto Rican communities that would subsequently develop in less urban areas or in areas outside of the New York metropolitan area, such as Hawaii, California, and Arizona and other southwestern states. Communities in Gary, Indiana, and Lorain, Cleveland, and Youngstown, in Ohio, began in this way (Senior and Watkins, 1966). Contract labor migration began soon after 1898 and has continued throughout the twentieth century. Indeed, the very first group to migrate to the states after the 1898 takeover was a group of contract laborers who went to Hawaii. For many, the farm labor system was the "stepping stone to residence in the U.S. usually in urban areas" (Maldonado, 1979:117).

Class and Selectivity

The class composition of the Puerto Rican communities has changed over time, but they have always retained a distinctive diversity. We know that the nineteenth-century Puerto Rican community was generally made up of well-to-do merchants, political activists closely allied with the Cuban revolutionary movement, and skilled workers, many of whom were tabaqueros (skilled tobacco workers) (Iglesias, 1980; Sánchez-Korrol, 1983). By the first quarter of the twentieth century, the Puerto Rican community was described by a number of scholars as consisting of people who were employed in predominantly working-class occupations (Chenault, 1938; Gosnell, 1945; Handlin, 1959). In the post-World War II period, migration from Puerto Rico to the United States accelerated, causing the communities to grow rapidly. The composition of these communities continued to reflect diversity, but with a strong working-class base.

A related question that has preoccupied researchers is who exactly migrated to the United States; that is, were those who came the best or worst of the lot? With increasing numbers of immigrants from Asia and Latin America currently coming to the United States, and with evidence of differential group outcomes, there has been a renewed interest in this question. Implicit in this question (today) is whether differential group outcomes are the result of who came.2 Further, there is concern over the declining quality of immigrants; the question is asked whether there is negative selectivity with regard to those who come and those who return (Borjas, 1987; Chiswick, 1977; Jasso and Rosenzweiz, 1982).3

Research interest in the human capital characteristics of Puerto Rican migrants has fluctuated over time. Throughout the post-World War II period, there were a number of scattered cross-sectional studies that give us partial but intriguing answers to the question of who came. The early studies seemed to emphasize the superiority of the migrants relative to those who did not migrate. For example, a 1948 study of more than 1,000 Puerto Rican migrants in New York found that the migrants had higher literacy rates (93%) than those who stayed in Puerto Rico (74%), that the migrants were predominantly skilled and semiskilled (only 26% were unskilled), that most of the migrants had been employed prior to migrating (69% of the men had been in the labor force), and that few had come from agricultural areas—indeed, 82% had been born and raised in the three largest cities on the island (Mills et al., 1950: 22-42; Senior and Watkins, 1966: 708 ff.).4 An analysis of the 1940 census found that Puerto Ricans living in the United States had twice the average years of schooling of those in Puerto Rico (Senior and Watkins, 1966: 709).

Thus, up until the period of "the great migration," the "superiority of the migrant" was confirmed in the literature. However, subsequent studies that examined the post-1950 communities did not echo the "superior migrant" thesis, but focused more on the problems experienced by the migrants in the cities (see, for example, Wakefield, 1959; Padilla, 1958; Rand, 1958; Glazer and Moynihan, 1970; Sexton, 1966). Indeed, Senior and Watkins (1966) note that the average years of schooling ratio (between migrants and those still in Puerto Rico) was reduced in the 1950 and 1960 censuses.5 They attribute this to increased numbers of "followers" as opposed to "deciders" coming as a result of the "family intelligence service." These followers were younger and from more rural backgrounds. In short, in the 1940s the migration was seen to be an urban, skilled migration, involving a predominance of women. In the 1950s, the migration was described as a predominantly male, unskilled, and rural migration.

Although the literature on Puerto Ricans in the states changed in focus, the evidence suggested that aside from higher proportions of rural migrants, the educational level (or "quality") of the migrants continued to be superior. For example, the ramp surveys conducted by the Planning Office in Puerto Rico between 1957 and 1962 found that each year showed increasing English proficiency and higher literacy levels among migrants than among the population as a whole, despite the fact that the majority of migrants during these years were coming from rural areas (Senior and Watkins, 1966).6 Two subsequent islandwide surveys, made between 1962 and 1964, also found the migrants to have higher literacy rates than those on the island, and than previous migrants, and to come in the main (62%) from rural areas. Sandis's (1970) analysis of the Puerto Rican migrant population in the United States during the 1960s also showed educational and occupational selectivity relative to the island population. Finally, a U.S. Department of Labor (1974: 373) study of Puerto Ricans in poverty areas of New York in 1968–69 found that migrants still exhibited higher educational levels and English proficiency than those on the island.

The most recent comparison of migrants and nonmigrants finds migrants to have higher median levels of education—10.9 years, compared to 9.4 for the population of Puerto Rico as a whole.7 This study also found higher proportions of college graduates among the migrant group—10.5% versus 9.4% for nonmigrants (Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico, 1986: 20 ff.).

Why Did Puerto Ricans Come?

This question has been asked continually in the literature, and has resulted in numerous answers. For example, early theorists such as Chenault (1938) and Handlin (1959: 50 ff.) argued that overpopulation in Puerto Rico was the major factor inducing migration,8 and that this overpopulation had come about as a result of health and medical improvements made under U.S. policies (Sánchez-Korrol, 1983). Senior and Watkins (1966), Mills et al. (1950), and Perloff (1950), on the other hand, argued that the pull of job opportunities was the major factor motivating migration. More recent researchers have tended to see migration as a response of surplus labor to the economic transformations occurring in Puerto Rico. Influenced by the larger context of economic and political dependence, these transformations have yielded increasingly larger numbers of displaced and surplus workers who were forced to migrate elsewhere for jobs (Reynolds and Gregory, 1965; Maldonado-Denis, 1972; Bonilla and Campos, 1981; Morales, 1986; Uriarte-Gastón, 1987; Padilla, 1987b).

More micro-level analyses have also examined economic push and pull factors (Fleisher, 1961, 1963; Glazer and Moynihan, 1970; Reynolds and Gregory, 1965; Pantoja, 1972; Rodríguez, 1973; Sánchez-Korrol, 1983). It has been found that when U.S. national income goes up and unemployment goes down, Puerto Rican migration increases. Relative wages and unemployment rates in Puerto Rico and the United States have also been found to affect migration to the United States and back to Puerto Rico (Fleisher, 1963; Friedlander, 1965; Maldonado, 1976).9 Thus, Puerto Ricans migrate when job opportunities look better in the United States and/ or when those opportunities appear worse in Puerto Rico. It has also been found that Puerto Ricans do not migrate to secure greater welfare benefits (Maldonado, 1976).

Other researchers have emphasized the role of U.S. companies in recruiting Puerto Rican labor to work in the United States (Morales, 1986; Maldonado, 1979; Piore, 1979; Lapp, 1986; Uriarte-Gastón, 1987).10 Originally, Puerto Ricans were "greatly valued" by their employers because of their citizenship status and their agricultural backgrou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Colonial Relationship: Migration and History

- 2 Beyond the Census Data: A Portrait of the Community

- 3 The Rainbow People

- 4 The Political-Economic Context

- 5 Housing and the South Bronx

- 6 Educational Dynamics

- 7 The Menudo Phenomenon: An Unwritten History

- Appendix: Tracking in the School System

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author