![]()

Part I

Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy has been chosen as an example of a disabling condition. A primary reason behind this choice is its complexity, and the findings of research into attitudes towards people who have the condition,1 that “the cerebral palsied are seen by the non-handicapped - as a friend, co-worker, play-mate for child, marriage partner - less favourably than those with sensory handicaps or physical handicaps without brain involvement”.2

Chapter 1 will discuss cerebral palsy as a clinical condition. Chapter 2 will discuss the implications of this condition for the lives of children and their families.

Notes

Combs, R. H. & Harper, J. L. (1967) ‘Effects of labels on attitudes of educators towards handicapped children’, Exceptional Children, 33, 6, pp.399-403.

Tringo, J. L. (1970) “The hierarchy of preference towards disability groups’, Journal of Special Education, 4, 3, pp.295-306.

![]()

1 Cerebral Palsy: The Clinical Condition

This study is about what parents do when their child is diagnosed as having cerebral palsy; what choices they make based on their understanding of the medical assessment; what treatments, social services and educational facilities are available for them to use, through the mixed economy of welfare. The starting point, therefore, is to examine the meaning of cerebral palsy as a clinical condition; the nature of the syndrome; its causes, types and consequent impairments and disabilities; the range of treatments and corrective interventions available. It will become clear that this is a condition riddled with ambiguities. Uncertainty of diagnosis precedes slow realisation of the extent of the impairments. Causation may remain unknown and the effectiveness of interventions hard to assess. In the words of one mother:

Clinical knowledge should be seen as the foundation, the base line from which to embark on a study of the implications of the condition for social policy provision. Middleton’s concerns about ‘half-baked medical knowledge’ have some validity, but it will become clear that elementary physiology is useful to those without medical training.1 Furthermore, its inclusion is vital to making decisions about the suitability of social and educational provisions over and above those described as medical. Recognition of the importance not only of a clear diagnosis but also of intelligible, clinical explanations was a recurrent theme in many of the interviews with parents.

This need for parents to have a better understanding of cerebral palsy is endorsed by Scope (the Spastics Society) whose bibliography for parents includes sections on medical aspects and what are called technical books. These cover epidemiology, management and treatments. It is noticeable that voluntary organisations providing services and treatments usually provide pamphlets to communicate the clinical aspects of the condition to carers. Examples of these publications are available from the Bobath and conductive education centres. The Spastics Society of India has published a range of medically based pamphlets and promotional videos to increase understanding of this condition as a precursor to discussing rehabilitative interventions. Some of these are written and printed by people who have cerebral palsy.

Perhaps the dilemma of needing a clinical perspective as a starting point for deciding how to proceed as a parent is best expressed by Marion Stanton.2 As a parent of Danny, who at four months was diagnosed as having ‘severe, spastic, cerebral palsy,’ she wrote Cerebral Palsy: a Practical Guide. This book begins with a substantial and detailed clinical account of the condition including diagrams of the brain and detailed classification charts from Minear3 and Levitt.4 This information is then woven into the ensuing analysis of treatments and services. The intention is ‘to produce a publication which is easily accessible to all carers of children with cerebral palsy I have been extremely irritated by the text books about cerebral palsy which really can be understood only by professional people.’

This chapter, therefore, acknowledges that a clinical perspective is integral to this study and that it is the area which parents find difficult, partly from ignorance and partly from a combination of fear and shock. For parents in this study disability had been thrust upon them: neither they nor their family and friends had first hand knowledge of disability or of cerebral palsy as a clinical condition. Abbott and Sapsford noted that ‘parents are themselves members of the culture which stigmatises them and their children, and share to some extent the attitudes they are forced to combat’.5 As a framework for this analysis of cerebral palsy as a disabling condition, a profile of cerebral palsy will be presented, which will include a clinical account of its nature, causes and types. A discussion of impairments and disabilities will be followed by an overview of treatments and specialist rehabilitative systems specifically designed to maximise children’s potential.

Cerebral Palsy: The Condition

Cerebral palsy is the medical term used to describe ‘a group of conditions that have in common the fact that they are severe, congenital, non-progressive neurological disorders, affecting muscle control and movement’.6 Children with cerebral palsy have sustained irreversible brain damage and their condition is usually diagnosed either at birth or within the first eighteen months of life. Typical of parents’ accounts of discovering about their child’s condition is the following extract from interviews:

In some situations, the birth experience itself made the diagnosis a certainty.

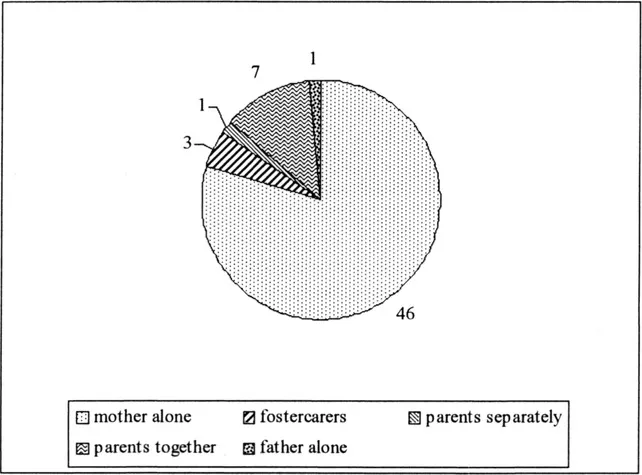

Most commons seems to be gradual realisation that a baby is not reaching developmental milestones. Only 16 of parents interviewed admitted to being told the diagnosis soon after birth, while 42 said they learned the diagnosis when their child was between three months and two years. (See figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 When diagnosed

Cerebral palsy may be best understood as a disorder caused either by malformation of the cerebral tissues or asphyxia (lack of oxygen at the time of birth) or bleeding in the brain, before, during or after the baby is born. When there has been bleeding, haemorrhage scars the brain, damaging the neurological system which controls muscle function. In the current state of medical knowledge, the damage cannot be repaired, and the outcomes or effects on the body are best described as similar to the effects of a stroke. However, in Bobrow’s words ‘the complex mechanisms whereby the brain directs muscle activity mean that there are many opportunities for things to go wrong....The sober fact is that we still do not know what causes the vast majority of cases of cerebral palsy’.7

Although incurable, this group of conditions is usually not progressive and has in common disorders of movement that seem to be responsive to corrective or rehabilitative interventions. It is thought that early intervention maximises functioning.8 When considering social policy issues, therefore, these children may be described as physically handicapped since the brain damage appears to interrupt the neurological system controlling muscle use. Clinical analysis of how body movement is controlled by the cerebral neurological system is the focus for research.9

This approach is vital to those exploring prevention and cure. For the purposes of parents, carers and social scientists, describing outcomes may be the most intelligible way to gain a workable definition of cerebral palsy. How the condition presents itself; how children with this condition are perceived and therefore how their needs may best be met is a useful starting point. Unfortunately confusion increases when attempting to approach the condition from this angle, because the amount of motor dysfunction varies considerably depending on the extent of the damage, the site in the brain where the accident happened and possibly the amount and type of early therapeutic intervention available. It also varies with the child’s inherently unique personality and the social and cultural conditions of the family. There are, however, some common distinguishing features.

Infancy

Babies with cerebral palsy are not easy to manage; they either fail to reach usual developmental milestones or reach them late.

Usually babies attain head control by five months; by six months they extend and use their arms for support, getting ready for sitting, standing and balance; crawling develops around seven months and babies walk before the age of two. Brain damage means that the baby has little head control; poor ability to use arms and hands for support, for reaching, grasping and manipulation, and consequently, little balance and control of posture for sitting, standing, and walking. Normal development of sequential motor control from head down to feet over two years may happen late, partially or not at all. Parents may be expecting this developmental delay if they have been told of ...