![]()

PART I

CONCEPTUAL

![]()

1

BIG DATA AND ANALYTICS IN GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATIONS

A Knowledge-Based Perspective

MATTHEW CHEGUS

Contents

Introduction

Literature Search

Managing Knowledge: Organizational Knowledge and Learning

The Public-Sector Context

The Role of Big Data and Analytics

Theorizing the Use of Big Data and Analytics in Public-Sector Organizations

Discussion

Appendix: Literature Review Search Terms and Findings

References

Introduction

Big Data Analytics (BDA) has been a popular topic in the private sector for some time. However, less is understood about its application in the public sector. With increasingly knowledge-based services dominating the economy, the cultivation and deployment of various forms of knowledge and the tools that enable it are critical for any organization seeking to perform well (Chong, Salleh, Noh Syed Ahmad, & Syed Omar Sharifuddin, 2011; Harvey, Skelcher, Spencer, Jas, & Walshe, 2010; Rashman, Withers, & Hartley, 2009; Richards & Duxbury, 2015). Private firms often acknowledge the impact of organizational knowledge on innovation and firm performance (Walker, Brewer, Boyne, & Avellaneda, 2011). Yet, findings related to knowledge management (KM) in public-sector organizations have been somewhat mixed (Choi & Chandler, 2015; Kennedy & Burford, 2013; Massingham, 2014; Rashman et al., 2009). Some draw parallels between private and public organizations, where both maybe delivering some type of service (Choi & Chandler, 2015), whereas others caution that the application of private-sector organizational knowledge frameworks to public bodies might be untenable due to the differences in organizational environments such as ownership and control (Pokharel & Hult, 2010; Rashman et al., 2009; Riege & Lindsay, 2006; Willem & Buelens, 2007).

Furthermore, just as theoretical insights differ, the use of technologies and tools differs between public and private organizations. It has been argued that BDA initiatives in public-sector organizations are generally underutilized and the value returned is less than expected (Kim, Trimi, & Chung, 2014). Conflicting goals, changing leadership, stewardship of values, and challenges in measuring outcomes are all thought to constrain the use of BDA in public organizations (Joseph & Johnson, 2013; Kim et al., 2014; Washington, 2014).

Ultimately, public-sector organizations serve the people, and it is this ideological orientation and the ensuing stakeholder relationships that determine the appropriate use of BDA and delineate the differences in application from the private sector (Riege & Lindsay, 2006; Walker et al., 2011). The processes associated with BDA can be used to effectively manage knowledge and thus produce better program outcomes if employed not just to collect and store data but also to learn from these data to create meaning and insight. This article, therefore, is an exploration of the current literature on organizational knowledge and its related fields such as organizational learning (OL), in an effort to develop a conceptual framework for the successful application of BDA in the public sector. To do so, a literature review on KM, OL, and BDA was conducted to identify current thinking related to the public-sector context. This document briefly defines the literature search, explores concepts of knowledge as it relates to public-sector organizational conceptual framework, and then discusses the framework developed based on the findings from the literature review. A series of propositions based on the conceptual framework is then provided.

Literature Search

A systematic literature search was conducted in combination with more directed literature reviews. We started with seminal works in KM to provide initial direction and insight and then conducted multiple searches of the recent literature through the Web of Science citation database and ABI/INFORM Global with key words relating to KM, OL, information technology (IT), and BDA. Three questions drove the search for current literature pertinent to a discussion on KM and BDA in the public sector: What are the key elements of effective KM in the public sector? What differentiates use of BDA in public organizations from that in private firms? How can public-sector organizations effectively manage knowledge supported by BDA? The initial searches, along with their search terms and findings, are described in the appendix.

Managing Knowledge: Organizational Knowledge and Learning

To better define a conceptual framework for BDA, it makes sense to first address the concept of organizational knowledge and learning. The use of knowledge in the organization is generally related to helping individuals and organizations learn, and the hierarchy of data, information, and knowledge is a well-discussed notion. However, the literature review suggests that the strict separation between data, information, and knowledge might not, in fact, be entirely appropriate to the ways in which organizations use knowledge.

Authors such as Polanyi, Dewey, Penrose, and Hayek have contributed to different theoretical perspectives of knowledge (Rashman et al., 2009). Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001), and others have extended such insights by exploring conceptual models of knowledge within organizations. A core theme, discussed extensively by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), is the distinction between tacit and explicit forms of knowledge. Within this conceptualization, data would be considered explicit: it describes the specific circumstances of the moment and so maybe more easily measured and recorded through concrete means. From a constructivist perspective, knowledge, being inherently more generalized, is more abstract and subject to all manner of individual perception. However, Nonaka and Takeuchi argue that such distinctions between explicit and tacit knowledge maybe a false dichotomy; the more generalized form may not exist without the specifics from which those generalized patterns were abstracted.

Data may thus be seen as the lowest level of informational units comprising an ordered sequence of items that becomes information when the units are organized in some context-based format. That is, information emerges when data items are generalized from a specific context such as an organizational problem or opportunity. Knowledge has been represented as the ability to draw distinctions and judgments based on an appreciation of context, theory, or both (Tsoukas & Vladimirou, 2001). More particularly, organizational knowledge would be created through a process of cognitive assimilation where decision makers consider information abstracted from a specific context (Richards & Duxbury, 2015), leading to an understanding of the current situation and the organizational response required (Tsoukas & Vladimirou, 2001).

The putative relationship between data, information, and knowledge appears to be that knowledge is built upon contextualized information units lower in the hierarchy. That is, the knowledge creation process is sequential, starting with data as its lowest level. At each subsequent level, individuals attempt to generalize in order to gain context-specific insight. This process of generalization is helpful as it allows information to be utilized in many more circumstances, patterns to be seen between divergent applications, and lessons to be learned from a variety of experiences. However, generalization may also be problematic. Generalization from specifics may seem relatively straightforward, but such conclusions maybe difficult to apply to other specific circumstances if overgeneralized or oversimplified, or otherwise, inappropriate inferences are made. Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001) caution that individuals understand generalizations only through connecting them to particular circumstances. Fowler and Pryke (2003) raise a similar alarm, noting that, as discussed previously, knowledge is not just objective information but also the perception arising through each persons’ experiences. Thus, a tension maybe seen between the specific form of information (data) and the more generalized form of information (knowledge) that gives credence to the notion that there is some kind of information flow between apparently distinct categories of knowledge.

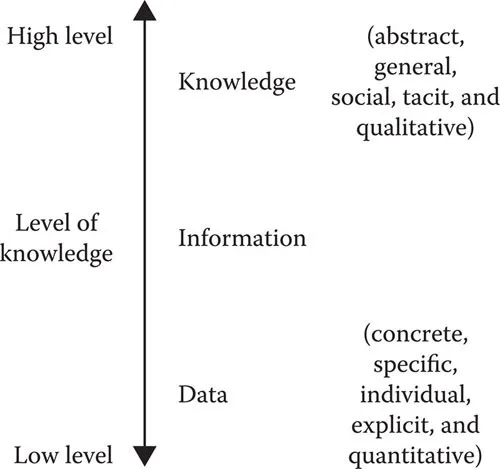

This paper not only recognizes that different forms of knowledge are related but also supports Nonaka and Takeuchi’s idea that such distinctions maybe false dichotomies. Specifically, this paper asserts that the only meaningful distinction between data, information, and knowledge is the level of generalization. The current notions of explicit knowledge exist as observable artifacts (such as a direct empirical measurement), whereas tacit knowledge is generated through the abstract process of cognitive assimilation. This reasoning leads to the model shown in Figure 1.1, where dimensions of knowledge range from low level (data) to high level (knowledge). However, how one may abstract knowledge from data is the resulting question of this assertion.

Pokharel and Hult (2010) describe learning as acquiring and interpreting information to create meaning. Indeed, other authors share similar sentiments. Barette, Lemyre, Corneil, and Beauregard (2012) described different schools of thought from cognitive-based learning to social constructivist learning; the former is characterized as changes in information based on reflections of individuals, whereas the latter is more the result of multiple people sharing their specific experiences and extracting commonalities. All three perspectives relate specifics to generalities through some sort of process or transformation indicative of Richards and Duxbury’s assimilation. Barette et al. (2012) reflect this notion by saying “Knowledge management and OL models overlap in terms of common fundamental concepts related to learning” (p. 138). Fowler and Pryke (2003), Chawla and Joshi (2011), Kennedy and Burford (2013), and Harvey et al. (2010) echo similar observations. Learning, therefore, maybe considered the process by which information is generalized and abstracted to produce knowledge transitioning from lower levels of data to higher levels of knowledge.

Figure 1.1 Dimensions of knowledge.

As individuals undergoing this process would be relying on their previously acquired information, the process of learning would necessarily be influenced by all the previously acquired information, making learning a highly subjective affair. What one might recognize as a pattern might only be so because of previous patterns observed, for example. This would imply that learning is highly path-dependent, tacit, and idiosyncratic: “knowledge is not just objective information, but also is as much about the perception arising when information is refracted through the individual’s personal lens” (Fowler & Pryke, 2003). These learning idiosyncrasies support the existing notions of the subj...