Rhetoric and Reality

The rhetoric of the American political system promises much, but the reality of the system is that little appears to change. The rhetoric arises in response to demands made by various constituencies, interest groups, and influential individuals when canny politicians promise to meet the demands. But it is a long way from the rhetoric of promises to the reality of actions. Even the well-intentioned politician faces a tangle of congressional and bureaucratic red tape in getting his or her rhetoric to the point of realization. An intervening step of considerable importance is the step from promises to public policy. For starters, we can consider public policy to be plans for acting in the public interest.1 Very much in the public interest are human rights that many of us have come to take for granted—the right to education, health care, equal opportunity, law and order, a just government, and human dignity—yet these are things that more and more fall under the purview of the federal government.2

How well does the federal government administer programs connected with these public rights? If we believe only a small part of current political rhetoric or of current and recurring news headlines, the answer is “Not well at all.” Apparently, billions of tax dollars have been squandered, pilfered, or lost in the past few years. Equally apparent, basic rights of citizens are still inaccessible to large numbers—witness the sad state of the federal government itself as an “Equal Opportunity Employer,” the nagging inequities in income and taxation, and the maldistribution of health services. And all of these glaring failures have been reported by agencies of the federal government itself!3 It is apparent that even when good ideas, expressed in the rhetoric, find their way into public policy, they often fall on hard times in the process of implementation, the next step in the policy process. Then comes the question of what effects have been realized “in the public interest” as re-suits of the plans and actions. Finally, if there are no effects—or if there are undesirable, unanticipated effects—are the original plans and actions reviewed and modified?

Grossly simplistic as the above statements might seem, they outline the conceptual framework that should be used most in the study of policy; but rare indeed is the look at policy that includes all of the basic elements.4 In this book, we will consider the presidential use of policy commissions as one form of response to the demands made upon the political system. This is only a small part of the policymaking process, but a part that captures the essential elements: political demands, response to demands, and the way in which rhetoric becomes a type of reality through policy. To begin, we will explore the various views of public policy, how it comes about, who makes it in general, and the place of the president and presidential advisory commissions in the overall process.

Public Policy—How Public Is It?

There can be no debate about the effects of public policy; they exist clearly in every conceivable facet of American life—education, reproduction, work, leisure, the food we eat, the air we breathe, the water we drink. In terms of public knowledge, however, policy is not public. What it is, how it is made, who makes it, and how it works are not generally known. Usually the first information that reaches the average American citizen is the response of “Sorry, but that’s our policy.” In other words, it is often difficult to recognize public policy until it is too late to do anything about it.

Policy Action and Inaction

There are many views of what public policy is, is not, does, and does not. Public policy has been defined as the development of new programs; as the actions of new programs and of existing programs; as “just plain words”; as the results of actions; as the absence of programs and actions; and as the effects that result from the absence of planned programs.5 According to one noted policy scientist, it is so difficult to define policy that we should not even try.6 However, perhaps the definition of public policy as plans for acting in the public interest can be considered a viable one.

The development of new programs and the strengthening and redirecting of existing programs are policy actions. These actions are not policy in and of themselves; they are responses to policy. One kind of policy action, called acquisitive action, is based on the idea that resources—personnel, operating budgets, and facilities—are acquired as an initial step in the implementation of policy. The implementation of policy involves a second type of policy action, called implementai action. To put it loosely, implementai actions “administer” the programs connected with public policy. These actions give dollars, provide services, and regulate access to education, health care, housing, and voting. Obviously, some benefits are tangible, and some are not. Health, educational attainment, housing, and voting can be measured and implemented, but human dignity and happiness—or “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” if you will—are intangible and more difficult to implement. “Just plain words” denotes the third type of policy action, rhetorical action. Talk is cheap, and it appears that much public policy is dissipated in rhetorical action. However, rhetorical actions, acquisitive actions, and implementai actions can have tangible effects, whether the actions occur singly or in the combinations possible. The effects are policy impacts or policy results.7

To complicate the issue a bit, it is quite possible that there will be no results at all. There are many such examples: welfare, medical care, education, wages, social participation, political participation, and human dignity evidently do not find their way to all Americans in spite of massive levels of rhetorical, acquisitive, and implementai actions.8

There can be policy results, or things that look like policy results, with no policy and with no policy actions. For example, the Selective Service System, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare have spent a lot of time in recent years explaining just how it happened that they were carrying out discriminatory and/or illegal actions. Surely, there was no policy that directed the Selective Service System to draft large numbers of minority-group members so that disproportionate numbers of blacks would die in Vietnam. No public policy directed FBI and CIA agents to violate the civil rights of political dissidents. It is to be hoped that welfare programs did not intentionally set out to drive fathers and husbands from low-income families.

The lack of public policy can be as significant as the existence of policy. If public rights are accessible to all, then there is no need to worry about the policy or even wonder if there is a policy. On the other hand, if the accessibility is woefully inadequate or unequal, then we look for the policy involved. If there is a policy or plan and it is not working, then it should be changed. In the absence of such a plan, we must at least prepare to make one.

How Is Policy Made?

One assumes that public policy is conscientiously made and that lack of policy or lack of successful policy implementation brings about the search for new and better policy. This sounds suspiciously like the democratic method. As Schumpeter asserts, “Democracy is a political method, that is to say, a certain type of institutional arrangement for arriving at political—legislative and administrative—decisions.”9 Since a decision can be something other than a plan for acting in the public interest, the making of public policy is not “democracy in action”; rather, policymaking is one type of institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions. The decisions might be made democratically, and the institutional arrangements might or might not be democratic, but it is enough for now to consider that policymaking is a conscious process that is part of the political process.

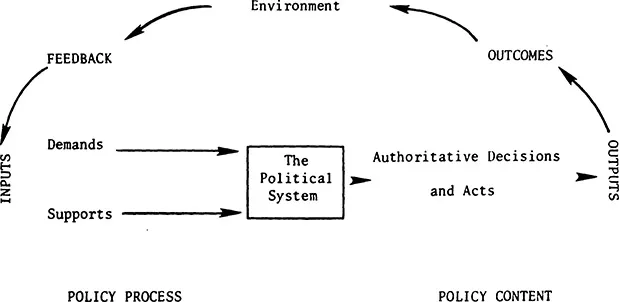

Easton proposed a policy model that captures these notions

Figure 1.1 Easton’s Policy Model

of process and results (Figure 1.1). Proposed in the model is a process of inputs and outputs. Demands, which were mentioned earlier, are made upon the political system. Appropriately or inappropriately, these demands might result in public policy, and the policy might be the cause of policy actions—rhetorical, acquisitive, and/or implementai. The actions might have results, and the results might satisfy the original demands. All of these “mights” are conditioned by the presence and quality of the other elements of the policy model. For example, some demands just do not catch the attention of the political system; other demands are not to be ignored. The supports input consists of information relevant to the demand and relevant to the costs and benefits—tangible and intangible—that are involved with the decisions and acts that compose the policy content’s first step, the policy actions. The outputs are the resources directed into acquisition and implementation. The outcomes or results may take place within the environment, or they may fall short of any perceivable change in the environment. The model runs full cycle when the environmental effects, or lack of effects, return as further inputs.10 Clearly, even with this brief overview, it would be extremely difficult to follow every public policy through such a process.

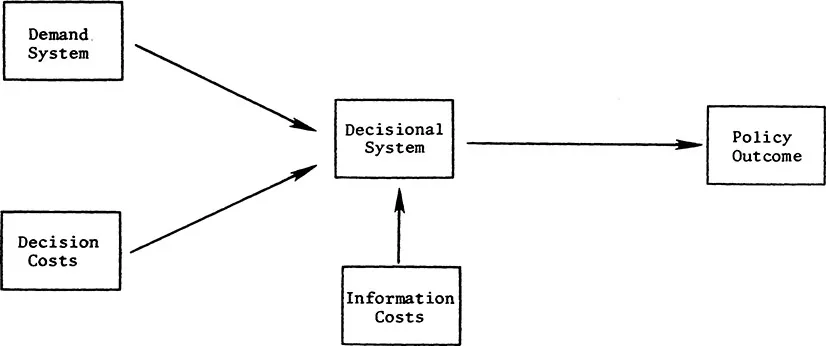

Salisbury and Heinz propose a policy model that simplifies the view somewhat (Figure 1.2). Their input-output notion is similar to that of Easton, and additionally, their model suggests that a relationship exists among demand, costs, and policy outcome, through the decisional system. However, Salisbury and Heinz indicate that the demands come from a system, and Easton’s supports are indicated in terms of costs. The characteristics of the demand system, of the decision system, and of the costs involved result in different kinds of policy outcome, according to Salisbury and Heinz.11 These differing outcomes include the policy actions and results discussed above, and they will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Who Makes Policy?

Who, or what, makes public policy is a tricky question. If the what is considered, then the answer could be “the decisional system” or “the political system.” More specifically, the answer could be “the president,” “the Congress,” “the Supreme Court,” or “the executive branch.” As for the who, the decisional system could be anybody; the political system could consist of millions of persons; the president is one; the Congress is hundreds; the Supreme Court is nine, and the executive branch is millions. If we trace the flow of authority in American government from the Constitution, from practice, from legislation, and from judicial decree, we come up with the three branches of the government as the most likely candidates for what and who. Realistically, the place of the Supreme Court is an after-the-fact role, for the most part, although many Supreme Court decisions have certainly attained the status of public policy, especially in the cases discussed above as failure of policy and absence of policy.12 But a more active role in making public policy is assumed by the president—and the executive branch—and Congress.

Figure 1.2 Salisbury and Heinz’ Policy Model

Continual high interest in the relationship between the executive branch and the Congress is a good indication of the importance of the policymaking roles of initiation, exercise of powers, and limitations of powers. Other areas of study have dealt with the comparative efficacy of each branch of government, usually with the implicit title of “The President vs. Congress: Who’s Winning?” There are accusations and counter accusations that the president has too much of this and that Congress does too little of that. The president has too much power or too little, as the case might be. The same charges and complaints are made about Congress. These are meaningful questions and answers, which will be discussed subsequently.

For now, the following should be considered: public policy consists of plans for acting in the public interest, public policy is made, and the president and Congress are extremely important in the policymaking process. While this might appear to be an oversimplification, it is actually a strong statement that excludes many of the issues that have confounded public policy’s being made public. That is, the actio...