- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Molecular Biology of Fungal Development

About this book

Providing an overview of the fundamental aspects of molecular fungal development, this book covers different elements in the maturational and reproductive cycles of selected fungal taxa. Illustrating various molecular pathways in parasites and hosts, the book explores the development of interventional strategies for combating disease. Highlights in

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Molecular Biology of Fungal Development by Heinz D. Osiewacz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Pseudohyphal Growth in Yeast

Hans-Ulrich Mösch

Institute for Microbiology and Genetics, Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen, Germany

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Definition and Importance of Yeasts

Yeasts comprise a group of ~700 ascomycetous or basidiomycetous fungi, whose predominant mode of vegetative reproduction is growth as single cells [1]. In other words, growth as unicellular organism is the main criterion that unifies taxonomically diverse fungi as yeasts. In addition, many molds that predominantly grow as hyphal filaments can adopt the yeast form as part of their life cycle. One of the prominent genera among yeasts is Saccharomyces, which has been used in making bread and brewing liquor throughout human history. The literary meaning of the terms used for yeasts in different languages can often be associated with the property of fermentation [2]. The English word yeast is related to the Dutch word gist or the German word Gischt which both mean foam. The French expression levure is derived from lever (=to rise) and the Latin term levere, both of which refer to the evolution of CO2 that pushes up solid substances during fermentation. Apart from Saccharomyces, many other yeast genera are of central importance in today’s biotechnology and medicine. Among others, strains of Schwanniomyces occidentalis, Kluyveromyces lactis, Pichia pastoris, Hansenula polymorpha, Yarrowia lipolytica, and Candida maltosa belong to the so-called nonconventional yeasts that are used in a wide variety of biotechnological processes of great economical importance [3].

A number of human pathogenic yeasts and medically important fungi with a yeast phase during infection have been described and include Candida albicans and other Candida spp. (causative agents for candidosis), Cryptococcus neoformans (cryptococcosis), Histoplasma capsulatum (histoplasmosis), and Blastomyces dermatitidis (blastomycosis) [4]. In basic biological research, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe are among the molecularly best-characterized organisms and have become model systems for the eucaryotic cell in general [5].

1.2 Dimorphism

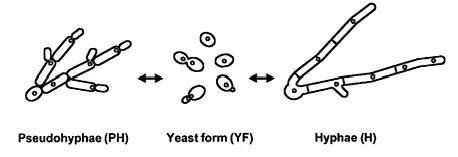

The unicellular growth form is the preferred mode of reproduction of yeasts. However, many yeasts are able to grow as multicellular filaments that consist of either pseudohyphae or hyphae (Fig. 1). Each of the yeast form (YF), pseudohyphal (PH), and hyphal (H) growth forms represents a distinct fungal cell type that is characterized by its cellular attributes and the mode of cell division (see below) [6]. The ability of yeasts to change between unicellular and filamentous growth phases is referred to as yeast-mycelial dimorphism and has long been used as an important morphological criterion for taxonomic and systematic classification of yeasts [1,7,8]. For the medical mycologist, dimorphism is a significant virulence factor characteristic for human pathogenic yeasts [4]. Numerous exogenous factors have been described that control interconversion among the different growth forms of yeasts and include specific nutrients, peptides, certain sugars, metal ions, oxygen, pH, and temperature [4,9]. Therefore, dimorphism of yeasts also serves as a general model for fungal development in response to external signals.

FIGURE 1 Vegetative growth forms of budding yeasts. In the yeast form (YF), cells divide by budding, followed by complete separation of the mature bud from the mother cell. Pseudohyphae (PH) originate from the budding of elongated cells that remain attached to each other, resulting in the formation of pseudohyphal filaments or pseudomycelium. Hyphae (H) and hyphal mycelium develop by continuous tip growth of hyphal cells, followed by fission of cells through the formation of septa.

The molecular mechanisms underlying dimorphism are far from being understood in detail, despite the fact that a wealth of information on the cellular and molecular biology of model yeasts like S. cerevisiae has become available [5]. A profound understanding of yeast-mycelial dimorphism requires the molecular analysis of all growth forms of yeasts and of the signals and regulatory networks that control interconversion among them. In a first step, easily tractable model organisms serve as initial source of molecular information. At a later stage, however, molecular studies must include analysis of dimorphic yeast species from a broad range of taxa.

2 GROWTH FORMS OF YEAST

2.1 The Yeast Form

By definition, yeasts prefer unicellular growth as their favorite mode of vegetative reproduction. The typical yeast cell reproduces by either budding, exemplified by S. cerevisiae, or fission, as in S. pombe [5]. Budding and fission both confer a unique relationship between cell growth and the sequence of events that constitute the cell division cycle. Budding is initiated by the emergence of a bud as a small protuberance from the cell surface (Fig. 1). Until cytokinesis, further growth is restricted to the bud. The bud lengthens in parallel to DNA synthesis (during S phase) and then swells to achieve its characteristic form during mitosis (M phase). Once the bud receives a daughter nucleus, it separates from the mother cell via septation and enters G1 as an independent daughter cell. Reiteration of this process rapidly produces a rounded pile of single cells, or colony, on the surface of solid growth media. Cell division by fission starts by cellular growth at both tips which leads to cell elongation and stops when mitosis is initiated. Upon completion of mitosis a septum is centrally placed in the dividing cell, and cell division occurs by binary fission. However, it is not the mode of cell division (budding or fission) that determines whether yeasts reproduce as single cells or build filaments. The crucial step that confers unicellular growth is complete separation of mother and daughter at the end of each round of cell division, whether cells divide by budding or by fission.

The yeast form has several advantages when compared to more complex growth forms such as branched hyphae [10]. Morphologically, the yeast form is a sphere. Although few yeasts are exactly spherical, most are spheroids with axes that differ only little in their length. Owing to their small surface area per unit volume, spherical yeast cells are very economical with cell wall materials. Because a single mother cell survives many cell divisions and produces up to 25 daughter cells, further wall material is saved. Yeast form cells are very resistant to osmotic rupture throughout cell division, especially when compared to the osmotically more fragile tips of hyphal cells. This attribute makes yeasts particularly suited for growth on their preferred natural habitat, the surfaces of plants, where they may be exposed to sudden changes in osmolarity owing to sudden rain. A further advantage of the unicellular nature of yeasts is efficient dispersal by water, air, or insects. In the case of pathogenic yeasts, the unicellular yeast form is probably transported more efficiently in the vascular and lymphatic systems of warm-blooded animals than the filamentous growth forms. In industrial processes, the yeast form of producing strains is often preferred over filamentous growth forms owing to easier handling of single cells.

2.2 Pseudohyphae

The development of pseudohyphae was observed and described in industrial yeast strains >100 years ago by Hansen [11]. Since then, the ability of yeasts to form pseudomycelia has been used as an important taxonomic criterion [1,8]. Pseudohyphal growth was accurately defined by Lodder [8], who wrote in 1934: “By pseudomycelium I understand septate, frequently branched filaments, which have arisen in such a way that the filament-producing, mostly longer cells are formed from one another by budding.” Thus, filament-building PH cells differ from single YF cells by an elongated morphology and the incomplete separation of mothers from daughters. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that both PH and YF cells reproduce by budding. A further difference between YF and PH cells was found in the early 1940s, when the microstructures of colonies of various yeast strains were analyzed in detail [12]. This study showed that certain yeast colonies consisted of a pile of single YF cells on top of the agar medium but that beneath the surface, pseudohyphal mycelium had developed and grown invasively deep into the agar substrate. Therefore, PH cells further differ from YF cells by their ability to grow invasively into substrates, suggesting that the development of pseudomycelia reflects a foraging mechanism that allows yeasts to explore new habitats. In pathogenic yeasts, pseudomycelium (along with true mycelium) is thought to be important for penetrating barriers of the host organism [4].

Pseudohyphal development is observed in a wide variety of yeasts including the genera Candida, Endomyces, Pichia, Saccharomyces, and Yarrowia [1]. However, pseudohyphal growth depends not only on the yeast species, but also on the growth conditions. In general, formation of pseudomycelium seems to be favored by poor conditions. Early observations showed that elongated cells and pseudomycelia are formed in cultures which have been grown at temperatures markedly below the optimum [11,13]. Partial anaerobiosis is another factor that stimulates the formation of pseudomycelium. This factor has found its application in the so-called Dalmau plate technique, where part of the surface of an agar streak is covered with a coverslip and where the portion of the culture beneath the glass produces pseudomycelium more readily than the other part of the culture [14]. This standard procedure for observing pseudohyphal growth on solid medium is still used for taxonomical classification of yeasts [1].

Filamentous forms are also frequently observed in older cultures, and fusel oils and higher alcohols appear to be at least in part responsible fo...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- MYCOLOGY SERIES

- ADDITIONAL VOLUMES IN PREPARATION

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- 1. PSEUDOHYPHAL GROWTH IN YEAST

- 2. HYPHAL TIP GROWTH OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS

- 3. CONIDIATION IN ASPERGILLUS NIDULANS

- 4. SENESCENCE IN PODOSPORA ANSERINA

- 5. VEGETATIVE INCOMPATIBILITY IN FILAMENTOUS ASCOMYCETES

- 6. VEGETATIVE DEVELOPMENT IN COPRINUS CINEREUS

- 7. BLUE LIGHT PERCEPTION AND SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION IN NEUROSPORA CRASSA

- 8. CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS IN NEUROSPORA CRASSA

- 9. SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT IN ASCOMYCETES FRUIT BODY FORMATION OF ASPERGILLUS NIDULANS

- 10. SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT IN BASIDIOMYCETES

- 11. SPORE KILLERS MEIOTIC DRIVE ELEMENTS THAT DISTORT GENETIC RATIOS

- 12. LIVING TOGETHER UNDERGROUND A MOLECULAR GLIMPSE OF THE ECTOMYCORRHIZAL SYMBIOSIS

- 13. DEVELOPMENT AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OF ARBUSCULAR MYCORRHIZAL FUNGI

- 14. PATHOGENIC DEVELOPMENT IN USTILAGO MAYDIS A PROGRESSION OF MORPHOLOGICAL TRANSITIONS THAT RESULTS IN TUMOR FORMATION AND TELIOSPORE PRODUCTION

- 15. PATHOGENIC DEVELOPMENT IN MAGNAPORTHE GRISEA

- 16. PATHOGENIC DEVELOPMENT OF CLAVICEPS PURPUREA

- 17. HYPOVIRULENCE

- 18. PATHOGENIC DEVELOPMENT OF CANDIDA ALBICANS

- 19. CRYPTOCOCCUS NEOFORMANS AS A MODEL FUNGAL PATHOGEN

- 20. MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF PATHOGENICITY OF ASPERGILLUS FUMIGATUS